Cornelisje Bakker 1816-1904

Early life 1816-1835

Cornelisje[Note 1] Bakker was born 19 February 1816, the second child of Theunis Bakker and Aaltje Snor, in the village of Oost-Vlieland on the isle of Vlieland. She had an older brother named Cornelis (b.1814). Her father was a carter, and they lived on Grote Strate, the main street running through the village[1]. The family would have spoken the Vlielands dialect of Dutch, which was closely related to the Dutch spoken on the Noord Holland mainland. The dialect became extinct during the twentieth century[2].

Few details of Cornelisje's childhood can be determined with any certainty, but she probably attended Oost-Vlieland's tiny village school, which was located in the poor house and was historically associated with the community church[3]. The Netherlands underwent substantial educational reforms in the early nineteenth century, and from 1806 every child was supposed to have access to a basic primary education in reading, writing and arithmetic, with provision being free to children from poorer families. Pupils would all be taught in the one classroom but separated into three groups based on ability rather than age[4]. However while the new regulations made these schools available, they did not make attendance compulsory, nor did they specify any age at which education should begin or end[5]. Cornelisje certainly had at least enough schooling to write her own name, but her handwriting was rather shaky, suggesting she was not a habitual writer.

Vlieland is home to a number of traditions and festivals, some of which stretch back centuries and would have been familiar to Cornelisje as she was growing up. There was a Meibrand ("May fire") every first of May, in which a huge bonfire would be burned on the waterfront. Pierepauwen (derived from French Pierre et Paul) was an All Soul's Day ceremony, in which children would dress in white outfits and veils, to symbolise the spirits of the dead. In December there would be a lively Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas) festival in which villagers would be divided into two groups. One half would dress up in masked costumes, and visit the homes of the other half, who would then have to guess who it was behind the mask. Once guessed, the costumed person got to stay at the guesser's house for a drink. Another tradition, found nowhere else in the Netherlands, was Wacht bij de doden ("Watch with the Dead"). Whenever an inhabitant of Vlieland died, the neighbours of the family would lay out the body the night before the funeral, and keep watch over the deceased by lanternlight until the following morning. The practice appears to be Roman in origin, and similar rituals can be found in some Catholic communities, yet it persisted on Vlieland long after the island's conversion to Protestantism, only dying out in the 1960s. Meibrand and the Sinterklaas festival have continued more or less unchanged up to the present day. Pierepauwen also still takes place, but now more closely resembles modern Halloween celebrations[6].

By the time she was twelve, Cornelisje had several younger siblings - Rijk (b.1818), Jacob (b.1822), Elisabeth (b.1824), Pieter Willem (b.1827). With Vlieland in serious economic decline[7], it may have been the family's struggle to feed so many mouths and the limited work opportunities on the island that prompted Cornelisje to leave her family home and set sail for the Noord Holland mainland. In 1830, we find her living in the naval port of Den Helder, in the household of her aunt Antje Snor and Antje's husband Adrianus Bouwen, a carpenter who worked at the docks. On the bevolkingsregister Cornelisje is stated as having no occupation, but she was in all likelihood working unofficially as a domestic servant to her uncle and aunt, and perhaps also as a nursemaid for their infant daughter Elisabeth (b.1828).

By the mid-1830s Cornelisje had returned to Vlieland, perhaps because her cousin Elisabeth was now a little older, and her uncle and aunt had no other surviving children, and so needed less support in the household. By now Cornelisje herself had another four siblings - Anke (b.1832), twins Theunis and Gerrit (b.1834) and Antje (b.1835) - so her assistance was perhaps needed more there than it was in Den Helder. The twins died within a few weeks of each other shortly after their first birthday. Out of Cornelisje's eight siblings, they were the only ones not to survive into adulthood.

On 21 February 1835 Cornelisje became a lidmaat (or "ledemaat" in the Vlielands dialect) of the Oost-Vlieland church, meaning she was officially indcuted as an adult member of its congregation. This involved a sort of coming-of-age ceremony in which young adults would typically recite a catechism to the priest to demonstrate their knowledge of church doctrine[8]. The closeness to Cornelisje's 19th birthday is probably coincidental, as due to Oost-Vlieland's small size it only admitted new lidmaten once a year. Cornelisje is listed as the last of thirteen people becoming lidmaten that day[9].

Family life in Den Helder 1836-1874

Cornelisje's membership of the Oost-Vlieland congregation would not last long. The following year she returned to Den Helder, this time permanently. She departed on or about 4 March 1836, carrying with her an attestatie (attestation) from Oost-Vlieland's church priest which would facilitate her entry into the congregation at her next place of residence[10].

Her reasons for return are not known, although they may have had something to do with a Den Helder native by the name of Albert Govers who she would enter into a relationship with, and may have gotten to know during her earlier stay in the port. Albert was a shipwright at the Rijkswerf, Den Helder's naval dockyard. This would have made him a colleague of Cornelisje's uncle Adrianus Bouwen, who also worked at the Rijkswerf. Cornelisje and Albert were almost exactly the same age, with Albert being just twelve days older. Judging by the birthdate of their first child, their relationship must have begun around the beginning of 1838 at the latest.

It would have been around this time that Cornelisje received the news that her brother Cornelis had died in November 1837. Having joined the navy at some point prior to this, he had been serving aboard the frigate Maas Stroom, stationed at the port of Rotterdam. His death record states that his body was pulled from the water, so presumably he had fallen overboard or from the dock. The death notification was made by an uncle on the Snor side of the family who also happened to be a mariner living in Rotterdam[11]. It seems plausible that Cornelis would have also stayed with their aunt Antje and uncle Adrianus Bouwen if and when his duties took him to the docks at Den Helder, so Cornelisje may have seen slightly more of him than she did her other relatives who had remained on Vlieland.

Cornelisje and Albert married in Den Helder on 6 September 1838. This was a mere three weeks before the introduction of a new Civil Code (De Burgelijke Wetboek), which required anyone below the age of thirty to gain proof of parental consent in order to get married[12]. Prior to this, marriage in the Netherlands was governed by the Napoleonic code, in which women could marry without parental consent at twenty-one, but men had to be twenty-five[13]. Thus Albert received the consent of his mother (his father being deceased), whereas Cornelisje needed no such approval. The timing of the wedding so close to this change in the law is perhaps coincidental, and could have more to do with the fact that Cornelisje would have been seven or eight months into her pregnancy at the time. There is no evidence to suggest that Cornelisje's parents would have objected to the marriage. There would however have been some effort saved in marrying when they did, as the new code would have required them to produce not only the testimonies of their parents but copies of several other documents such as their own birth certificates[14]. The official witnesses to the wedding were Albert's mother Dirkje Bakker (no known relation to Cornelisje), Johannes Harms (a shipwright and presumably colleague of Albert), Albert's half-brother Abraham Wentel, and a local butcher named Jan Frautschij[15]. Jan's wife was Jannetje Rab, a second cousin of Cornelisje's mother, which despite the distance of the relationship suggests perhaps that Cornelisje had stayed with them following her return to Den Helder.

The fact that Cornelisje was pregnant before the wedding is not remarkable, and there was in fact an old Noord-Holland custom known as Het Kweesten ("the questing") in which a young couple would be sexually active with each other as a sort of trial marriage, but a wedding would normally follow if the Kweesten led to pregnancy[16]. In Cornelisje and Albert's case however, they clearly left this somewhat to the last minute. The child was born six weeks later and named Arie, presumably in honour of Albert's father Aarjen, which Arie is a shortening of.

Following the marriage, Cornelisje, Albert, and their infant son lived at Tweede Straat No.186. This was probably one of several new streets that were being built around the docks, in a district then known as Loodsenbuurt after the nearby Loodsen canal. The city was growing rapidly, with a population now around 9,000. Only one third of these lived in the old town, which lay almost a kilometer to the west of the docks[17].

A second child was born in December 1839 and named Teunis Cornelis Govers. He would be the only one of Cornelisje's children to receive a middle name, and it seems that the family called him by this rather than his first name. This was a slight break with the traditional naming pattern then commonly used in the Netherlands, which Cornelisje and Albert otherwise adhered to, whereby the second son would be named after the mother's father[Note 2]. At the time of course Cornelisje could not have known how many sons she would eventually have, and it seems likely that she wished to take this opportunity to honour the memory of her departed brother.

Their third child was born in February 1842 and named Albert like his father. In April 1844 came Rijk, again named after one of Cornelisje's brothers, and Willem in April 1846, probably named after Albert's brother. Willem lived only 18 months, dying in October the following year. Although the cause of death was not recorded, disease was rampant in Den Helder, with malaria being particularly common due to the damp, marshy ground which was ideal for mosquitos. There were also problems with obtaining clean water, which lead to cholera outbreaks. Nutrition was often poor for working class families, with diets consisting mainly of potatoes and occasionally fish[18]. Cornelisje's family was probably somewhat better off than others thanks to Albert being a skilled worker, but with a growing number of mouths to feed and their eldest children not yet old enough to work, these must have been difficult times.

Cornelisje's next two children were her only daughters - Aaltje, born October 1848 and named after Cornelisje's mother, and Dirkje, born 1850 and named after Albert's mother. In 1850 the family appear on the bevolkingsregister, which reveals that all the children bar the two youngest were attending school. This was still not compulsory, but Cornelisje and Albert's children definitely received a good education, since several of her sons would later work in fields that required decent standards of literacy.

They were probably still at the same house on Tweede Straat, although it is rather difficult to tell, as since 1847 the local government had begun designating house numbers on documents simply according to wijk ("district"). Their address since then had been "Wijk C, No.328". I have not been able to find out exactly where this was. In around 1852 the family moved to Wijk D, No.185a, which later records would reveal to be Weststraat, which runs along the western side of the canal separating the Rijkswerf from the mainland. Den Helder was growing extremely quickly, as in 1851 its port had become open to cargo ships as well as naval ones[20]. Cornelisje's household had now been joined by Albert's half-sister Guurtje Wentel (born 1807), who was unmarried and had probably moved in when their mother died in 1852. Guurtje would stay with the family until her death in 1860.

In January 1853 Cornelisje gave birth to twins, named Jacob and Willem. Twins ran in Cornelisje's family, and she must surely have been reminded of her own twin brothers Gerrit and Teunis who died at a year old. Both Jacob and Willem would survive their infancy, but the family would not be spared from bereavement, since daughter Aaltje died in 1855 at the age of six. Another child was born later this year, and named Pieter after another of Cornelisje's brothers, followed by Abraham, born in July 1858 and probably named after Albert's half-brother Abraham Wentel. Cornelisje's twelfth and youngest child was born in September 1860, and named Teunis, which indicates that her second son Teunis Cornelis was probably known by his middle name. Sadly he was another who did not live long, dying in 1862.

In around 1859 Albert had been promoted to the position of Kommandeur, meaning he now had a senior, more managereal role at the Rijkswerf. The additional income this brought was no doubt very much appreciated by the family. Den Helder was also starting to modernise alongside its rapid growth. In 1856 gas streetlighting was introduced. In the same year it was linked to a piped water network, although only wealthy households could afford to be connected, the rest receiving their fresh water from waterboeren, literally "water farmers" who filled up barrels from wells further inland and then sold them door-to-door in the town[21].

Cornelisje's eldest children were now adults and in work themselves. Arie worked as a clerk or bookkeeper. Second and fourth sons Cornelis and Rijk followed in their father's footsteps, both becoming shipwrights, while third son Albert was a paperhanger. Most of the children stayed at their parents' home until they married, the first to do so being Arie in 1864. Cornelisje and Albert Sr acted as official witnesses, as they would at all of their children's weddings. Just two months later the household lost another son, when eight-year-old Pieter died. He would be the last of the children to die in childhood, with the remaining seven sons and daughter Dirkje all surviving well into adulthood.

The other older sons all married and moved out during the mid-to-late 1860s, but all kept within Den Helder, initially just a few doors away on the same street as their parents. This was the same address on Weststraat, where Cornelisje and Albert remained with their younger children Dirkje, twins Willem and Jacob, and Abraham. Due to the age gap between the older and younger siblings caused by the death of two middle children, there was no change to the household during the next five years. The elder children would all have quite large families, and by the beginning of 1875 Cornelisje had no less than twenty grandchildren.

Later years 1875-1904

The years 1875 to 1878 saw a great deal of change, both in Den Helder and within Cornelisje's family. In 1875 Cornelisje's only surviving daughter Dirkje married her first cousin Teunis Cornelis Bakker, who was the son of Cornelisje's brother Jacob. Soon after twins Willem and Jacob both got married within months of each other. Willem's wife was also a cousin on Cornelisje's side, albeit a far more distant one (a fourth cousin), which could either be coincidence or further evidence of the close ties families from the islands maintained when they moved to the mainland. While sea travel may have been too expensive for frequent journeys, it seems likely that literate members of the family would have kept in touch by writing letters. Later in 1876 Cornelisje would have received the news from Vlieland that her mother Aaltje Snor had died. Both her parents lived into their early eighties, her father having passed away several years earlier in 1870. Cornelisje's youngest sibling, Antje, also died in Vlieland in 1876.

Like their elder brothers before them, the three children who married in the mid-1870s all moved out of their parents house but stayed in the same part of Den Helder. However the youngest child, Abraham, would become the first to move away from the town. It was not of his own volition. In March 1878 his name was selected in the loting[22], a randomly-drawn drafting of young men into military service[23]. Later that year he would be posted to the city of Utrecht. Once again Cornelisje was probably reminded of parallels in the two generations of her family, with her brother Cornelis having joined the navy at a similarly young age, perhaps also via the loting.

Meanwhile, the growth of Den Helder was grinding to a halt. In 1876 a major canal was completed connecting the city of Amsterdam with the west coast. Suddenly, all trade from the Dutch capital could directly access the North Sea and no longer had to pass by Den Helder. The importance of the town as a commercial port collapsed almost overnight. The population began to shrink, and there was mass unemployment and a deepening of poverty[24]. Fortunately for Cornelisje, her family would have been protected from the worst of these changes as Den Helder remained the home of the naval dockyards. There may however have been some difficulties for several of the children. Perhaps finding a lack of wealthy clients with homes to decorate, third son Albert switched from being a paper hanger to a shopkeeper, possibly working with his younger brother Willem and his cousin and brother-in-law Theunis Cornelis Bakker, who are also recorded as shopkeepers around this time.

Albert retired in 1877 or early 1878. There were as yet no pensions, and poor relief for the elderly was a modest sum administered via the church. As such, men would typically work until they were absolutely no longer able[25], so Albert was probably in quite poor health. However, as all of Cornelisje and Albert's children were in steady work they were probably able to provide a little extra support for their parents, although the fact that they also had a large number of dependent children between them likely made money rather tight at times. Cornelisje and Albert now lived alone in their house on Weststraat, but other than Abraham all of their children lived no more than a few hundred metres away. Not all of them would stay for long however. Perhaps finding the economic downturn in Den Helder was no longer viable for their increasingly large families, Jacob relocated to Amsterdam in 1879, and eldest son Arie left for Haarlem in 1883. A year prior to that, Arie had filed for bankrupcy[26].

In June 1884 Cornelisje and Albert travelled to Utrecht for their youngest son Abraham's wedding, acting as signatory witnesses as they had for all the older children. Abraham had in fact fathered a child there some five years previously, and was now returning to marry the mother. This is the only evidence we have of Cornelisje travelling to anywhere besides Vlieland and Den Helder, and it demonstrates just how important family ties were to her, despite the family's middling financial situation. Three of the older brothers - Teunis Cornelis, Albert Jr and Rijk - were also signatories to the wedding.

In 1888 Cornelisje and Albert became great-grandparents when their granddaughter Maria Catharina, daughter of their third son Albert, gave birth to her first child Jan Verfaille. The family was now enormous, and Cornelisje had somewhere between forty-nine and fifty-eight living grandchildren, the majority of whom lived nearby[Note 3]. Those family members who had not moved away from Den Helder probably all attended the local Dutch Reformed church together, and in fact seem to have been quite involved within it. In 1884 Albert (Sr) and Teunis Cornelis were both proposed as candidates for the Confessioneele Vereeniging ("Confessional Association"), a mixed group of clergy and lay people who promoted Confessionalism, the practice of strict adherence to church doctrine[27]. In addition to their religious conservatism, the family were probably also staunch monarchists. One of Cornelisje's grandchildren, a son of Teunis Cornelis, was given the full name Willem Alexander Paul Frederik Lodewijk - the exact same given names of the then-king Willem III.

On 1st January 1890 Cornelisje and Albert joined many other Helder citizens in placing a New Year's greeting in a local newspaper. They were cosigning a short message from a neighbour, to which they added "Allen het goede toegewenscht" - "All good wishes". Their sons Teunis Cornelis and Willem were among those adding their names below this[28].

Albert died on 28 January 1893. A notice from Cornelisje and her children and grandchildren appeared in the newspaper the following day, which read:

"Heden overleed mijn geliefde echtgenoot en onze liefhebbende Vader-, Behuwd-, Groot- en Over-grootvader, de Heer Albert Govers, in den ouderdom van bijna 77 jaar"

Translation:

"Today my beloved husband and our loving father, father-in-law, grandfather and great-grandfather, Mr Albert Govers, died at the age of almost 77"

The notice was in the name of "de wed[uwe] A. Govers-Bakker en familie" - "the widow A. Govers-Bakker and family"[29].

Little can be said about the last decade of Cornelisje's life. She continued to live in the house on Weststraat she and her family had lived at since 1852, now occupying it alone. Aside from Arie, Jacob and Abraham, all her surviving children were still in Den Helder. The family of course continued to grow, her youngest grandchild (a son of Jacob) arriving in 1897, and more great-grandchildren appearing every year. By the time of her death, she had somewhere around one hundred living descendents[Note 4]. Six of her grandchildren were named Cornelia after her[Note 5].

Cornelisje died at 6 o'clock on the morning of 18 August 1904, at 119 Tweede Vroonstraat, the home of her son Willem and his family.

Notes

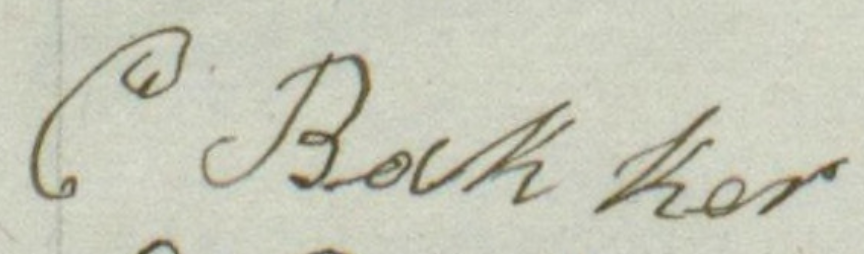

1. Her name appears in some places as Cornelia, which was by far the most common feminine form of Cornelis in Dutch[19], whereas Cornelisje appears to be a less common regional variant. She is Cornelisje on the records of her birth, lidmaat, marriage, and death, and bevolkingsregister entries made in 1830, 1860 and 1880. It is Cornelia on bevolkingsregister recordings made 1850, 1851 and 1856. It alternates on the birth records of her children, with Cornelia being slightly more frequent. Conversely it is Cornelisje on all but two of the marriage records of her children. Since she signed her own name as "C Bakker", we have no confirmation of which she would have used herself in formal or informal settings. However since Cornelisje is the variant that appears consistently on the records which are personally about her, I have assumed that this is the form which would have been used by her family and friends, and that the instances of Cornelia being recorded were simply examples of officials defaulting to the "standard" form. 2. The pattern, which can be found in other parts of northern Europe until the mid-nineteenth century[30], was as follows:

First son: Named after paternal grandfather (Aarjen/Arie)

First daughter: Named after maternal grandmother (Aaltje/Altje)

Second son: Named after maternal grandfather (Theunis/Teunis)

Second daughter: Named after paternal grandmother (Dirkje)

Subsequent children would then typically be named after the parents themselves, or the parents' siblings. Cornelisje's parents also followed this naming convention.

3. The records are a little patchy in places, and I have not been able to trace all of the grandchildren into adulthood. Forty-nine is the number who were definitely alive at that point, fifty-eight is the number who are known to have been born and are not confirmed to have died yet. Either way, it was a lot!

4. Again it is rather difficult to be certain, but at my best count in 1904 Cornelisje had:

- Her eight surviving childre: Arie, Teunis Cornelis, Albert Jr, Dirkje, Jacob, Willem and Abraham

- Approximately 61 grandchildren

- Apprpximately 28 great-grandchildren

for a total of 97 living descendents. 5. These granddaughters bear the name Cornelia on records, but are almost certainly named after Cornelisje, with Cornelia being a more common variant (see Note 1). The two children who did not have a child called Cornelia were Dirkje and Abraham, the latter of whom had no daughters at all.

References

1. Burgerlijke Stand Vlieland, Tresoar

2. Heeroma, K (1934): De dialekten van Vlieland en Midsland (Terschelling), published in De Nieuwe Taalgids, Jaargang 28; p24-25

3. SCahier, Jaargang 21, No.72, juli 2007, Architext; p21

4. Boekholt, P.Th.F.M. & de Booy, E.P. (1987): Geschiedenis van de school in Nederland vanaf de middeleeuwen tot aan de huidige tijd, Van Gorcum; p99

5. Onderwijswet, Bataafsche Republiek, 1806

6. De Boer, Johannes W. (2014): Religieus-culturele achtergrond van het eiland Vlieland in het verleen de moderniteit, Universiteit van Tilburg; p22-26

7. Ibid; p19

8. Brummelen, A van (1974): Belijdenis doen in de geschiedenis, De Waarheidsvriend

9. Lidmatenregister Hervormde Gemeente Oost-Vlieland, Treosar

10. Ibid

11. Burgerlijke Stand Rotterdam, overlijdensakten, Stadsarchief Rotterdam

12. Burgerlijke Wetboek, 1838; artikel 99

13. Nielsen, Marilou (2021): Als je wil trouwen maar niet mag van je ouders, Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum; accessed 19 Jun 2023

14. Burgerlijke Wetboek, artikel 126

15. Archiefdeel van (dubbele) registers van de burgerlijke stand van de gemeente Den Helder, Noord-Hollands Archief

16. De Boer (2014); p27

17. www.hansonline.eu, accessed 28 Jun 2023

18. Ibid, accessed 29 Jun 2023

19. Meertens Institut, accessed 20 Jul 2023 (note that the name can be changed in the "voornam" field to view figures for other names, and that the "verspreiding" button will show frequency by municipality.

20. www.hansonline.eu, accessed 29 Jun 2023

21. Ibid, accessed 29 Jun 2023

22. Lotingsregisters, Noord-Hollands Archief

23. Uit de oude Koektrommel, accessed 17 Jul 2023

24. www.hansonline.eu, accessed 29 Jun 2023

25. Van de Velden, Sjaak (2009): Geschiedenis van de Pensioenvoorziening in Nederland, Spanning September 2009, Socialistische Partij

26. Algemeen Handelsblad, 8 Mar 1882

27. Het Utrechts Archief, accessed 21 Jul 2023

28. 't Vliegend blaadje (Helder), 1 Jan 1890

29. Heldischer en Nieuwdieper Courant, 1 February 1893

30. Scotland's People, accessed 23 Jul 2023

To go back to the Govers-Oudegeest tree, click here