Hope Davis 1834-1916

Note: Since it was the name she went by as an adult, I have assumed that Hope is the name she preferred to be known by and have used it throughout. See also this note on the terminology I use when discussing my Roma ancestors.

Infancy 1834

Hope Davis was probably born in the first few days of 1834[Note 1], in or near the parish of Emborough in Somerset. She was the first and, as it would turn out, only child of Jonathan Davis and Amelia Hunt [1], two young Romani travellers. As per Roma custom she was probably born in a makeshift tent, or perhaps in the open air, as the act of childbirth was seen as impure and could not take place where the family lived and slept[Note 2].

Her parents named her Valentine[Note 3], after a younger sister of Jonathan who had died eighteen months prior. Appearing occasionally in the Davis family, the name may have been derived from a Romanichal surname which has been recorded at least as far back as the 1550s[5]. As a Romani name it was often spelled "Follintine" (or similar) in documentation, perhaps due to the accents of the Roma and the fact that most of them were illiterate so could not give their own spelling. Valentine is the name of a male saint, although it has appeared as both a boy's and a girl's name in Romani families. It is also possible that "Valentine" was in this case an alteration of an older Romani name, in which case "Follintine" may in fact be the more accurate rendering. When Hope's parents took her to be baptised at Emborough parish church, it was perhaps with some confusion or lack of interest in a family who would soon be moving on from the parish, that the cleric entered her into the baptismal register as "Florentine Davis".

Hope would have spent the first six months of her life travelling with the extended Davis family - her parents, her grandparents Lazarus and Priscilla, and several aunts and uncles. When just a week old, she was likely present at the wedding of her uncle Emmanuel Davis to Elizabeth Colin in Bedminster on the outskirts of Bristol. Around springtime the family moved northeastward into Wiltshire, probably travelling from place to place in an open-topped cart[6]. Once at a stopping place, Hope may have been carried in a sling on her mother's back[7], and accompanied the rest of the family in this manner as they visited local fairs to sell goods and offer services. Most nights they would have slept in tents, but may have sometimes stayed in lodging houses when they could afford it, especially through winter[8]. Social and legal persecution were a continual threat, with several members of the family (including Hope's mother Amelia) having previously served gaol time for vagrancy.

Hope seemed destined from birth to live a typical Romani traveller life just as her parents and many of her cousins did, and almost certainly would have done were it not for two drastic events which occurred before she was even a year old. In the summer of 1834 her father was arrested for the theft a horse, and was sentenced to be transported for life. After spending a few months in Ilchester Gaol, he was first sent to a prison hulk on the Thames, and then shipped to Australia the following year, where we can assume he ended his days. Amelia continued to travel, presumably either with the Davises or her own family, taking her infant daughter with her. She died very suddenly in November 1834, in an encampment on the Latterwood turnpike near the hamlet of Kingscote, aged nineteen. A coroner's inquest determined that she had died "by the visitation of God", and the burial register at Kingscote church described her as "a stranger who died by the roadside".

Childhood and early adulthood 1835-1856

To all intents an orphan, Hope would grow up not in tents and carts but in a house in the village of Theescombe, Gloucestershire, under the care of her maternal aunt Sarah, and Sarah's second husband James Smith. Since Sarah and James married in 1836, when Hope was two years old, the exact sequence of events leading up to her fostering by them is not clear. Theescombe is about two-and-a-half miles from Kingscote where Hope's mother died, and James had been in that area his whole life. One possible scenario is that James had offered to take Hope in, and Sarah had stayed with him to help take care of her niece, whereupon a mutual affection between the two adults had developed. Alternatively Sarah may have initially taken on the role of surrogate mother for her niece, and then met James through some other means, with his proximity to the site of Amelia's death being more or less coincidental. The latter theory is supported by the fact that Sarah and James married in the parish of Painswick several miles to the north, rather than Theescombe's parish of Minchinhampton.

Sarah was almost two decades older than Hope's mother, and her whereabouts between her first and second marriages are barely known, nor is it clear how recently she had been widowed. Her first marriage had taken place at Bedminster, the same place as Hope's uncle Emmanuel married. It appears that like James her first husband was a "gorger" (non-Romani), but they may have travelled with the Hunts or at least maintained close ties with them, as Sarah had witnessed a family wedding in Oxfordshire in 1819. Hope's foster father James was older still, having been born in about 1773. He was a cloth worker, and a long-serving lay preacher of Littleworth Wesleyan Methodist congregation[9], with Littleworth being a village adjoining Theescombe. He and Sarah had no children of their own, but James had several grown-up children from his first marriage, most of whom still lived nearby.

It was probably James and Sarah who chose to rename their foster daughter Hope. She appears under that name on a list of children attending the local Methodist Sunday school in 1843[10], indicating that she was known by it as a child. The choice of name seems quite obviously pertinent, with the implication being that James and Sarah were affirming their hope that they could give the infant a better chance in life.

It was nevertheless still accepted that Valentine (or at least some variant of it) was her official name. On the 1841 census she appears in the Smith household as "Follentine Davis". Although it is my assumption that she had been there since infancy, this is in fact our earliest direct evidence of her at her foster home. There is another child in the household named Elizabeth Davis, who is one year older than Hope. She was probably not a sister, as the criminal record of Hope's father states that he only had one child. She could have been an illegitimate daughter of one of Hope's aunts, some other relative via a cousin, or perhaps no relation at all since the name was common enough in the region. Perhaps like Hope she was taken in by the Smiths at a young age either because her parents died or were no longer able to care for her, in which case she would have effectively been a sister to Hope, although since the census only gives us a snapshot it is possible she only stayed with the Smiths for a short time. She cannot be reliably traced on any later records.

The census also shows several members of James Smith's family living in the same neighbourhood. Several doors away was Harriet, a daughter of James from his first marriage, and her husband Benjamin Teakle. In their household were James's youngest child Mary, and ten-year-old Thomas Smith, who was possibly an illegitimate son of Harriet born before her marriage.

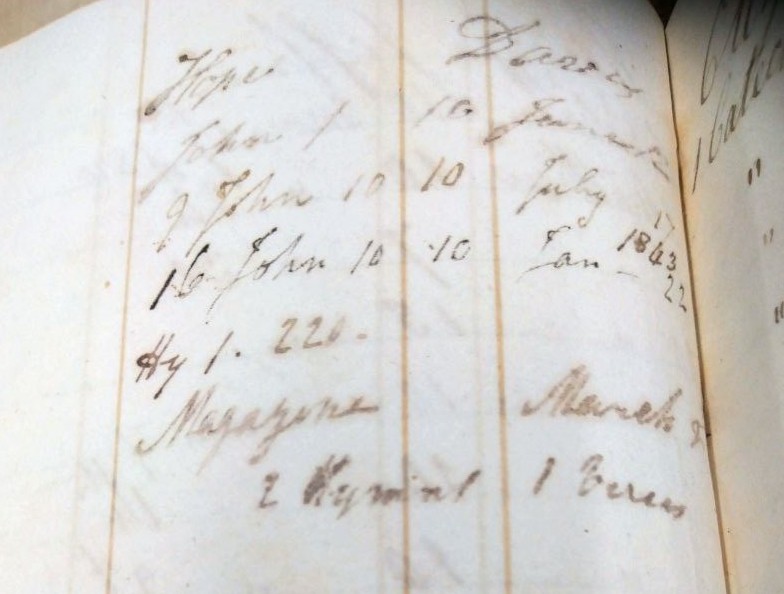

As her foster father was a Methodist preacher, Wesleyan teaching no doubt permeated Hope's childhood home. John Wesley's "General Rules" emphasised diligence and frugality, and an almost monastic observance of daily prayer and spiritual contemplation. Clothing was to be modest and spartan, the singing of songs or reading of books "which do not tend to the knowledge or love of God" was discouraged, and vacant hours were to be spent reading and meditating on the scriptures. Adherents shunned work every Sunday, and fasted every Friday[11]. Hope's Sunday school record lists several bible passages from the book of John, presumably ones she learned for catechism, and two hymns.

We can also assume that this Methodist upbringing was deeply disparaging towards Hope's Romanichal heritage. This was an era in which many evangelists were taking a special interest in English Roma, ostensibly with a kinder approach than that of the law, but with the same goal of essentially reforming them out of existence. A Wesleyan preacher from Southampton by the name of James Crabb described himself in 1832 as the "advocate of the gypsies", and would turn up at local encampments and begin preaching in an effort to convert their inhabitants to his faith. His writings, which stress the humanity of his subjects while simultaneously expressing disgust over what he called their "wretched and base" way of life, are quite typical of religious reformers of the period[12]. It would not be surprising if his work had an influence on James Smith, who clearly had his own interest in people of Roma descent.

It is of course also possible that Hope was taunted by other children because of her background, if they had known of it. On his gaol record, her father's complexion is described as "dark", so there is a chance that Hope inherited this trait and thus stood out from other local people.

Hope was to at least some extent informed about her birth family. She was aware that her father's name was Jonathan. She seems to have grown up believing that her place of birth was somewhere in Devon, as "Devonshire" (as it was then called) would be written on most of her census appearances. Whether members of her extended family ever stopped to visit we cannot know. Two of Sarah's surviving sisters and their families now travelled primarily through Devon, which could have served to fuel the impression that Hope was born there. Sarah's brother Thomas was somewhat closer, having settled in Oxfordshire in the mid-1840s, becoming the only other Hunt sibling to have given up travelling. Christiana, whose marriage Sarah had witnessed in 1819, travelled through Wiltshire and Somerset. On the Davis side, Emmanuel is the only one of her uncles or aunts known to still be living. He mostly travelled in Somerset, but in 1840 was sentenced to a month's hard labour for vagrancy at the Horsley House of Correction, just a couple of miles west of Theescombe. Hope's grandfather Lazarus Davis died in Somerset in 1839, while her grandmother Priscilla Davis would die in Warwickshire in 1858, but her whereabouts in the interim period are unknown. It is not clear whether Hope's grandparents on the Hunt side were still living during Hope's childhood.

Aside from Sunday school, Hope probably had some form of basic primary schooling during the week, with the most likely venue for this being the Littleworth Wesleyan school, which was in existence from at least 1838[13]. Education was another cornerstone of Methodism, and from 1836 the Wesleyan Education Committee was establishing weekday schools to give children (in its own words) "the influences, instructions, and restraints of a well regulated and happy Christian family".[14].

This provision however generally only covered primary education. In her teenage years Hope joined the region's largest industry and began working at a woollen mill. She was a burler, a job often given to younger women which involved checking the fibres and removing any clumps or knots[15]. Working hours were probably long, although from 1848 it would have been limited to a still-gruelling ten hours a day, with a weekly maximum of fifty-eight hours. If she was working prior to this she may have had to work twelve hour days under the previous legislation[16]. There were numerous mills throughout the district, the nearest to where Hope lived probably being either Inchbrook Mill[17] or Dyehouse Mill[18], both on the Nailsworth Stream.

From at least 1851 (and quite possibly well before), Hope's aunt Sarah was the mistress of an institution known as a Dame School. These were quite common in poorer neighbourhoods before the introduction of state schooling, and would typically be run by the school mistress from her own home, taking in local children for the day in exchange for a small fee while their parents were at work. Some would teach literacy, arithmetic and household skills, while others were effectively just day care centres[19]. In common with the vast majority of Roma, Sarah had not learned to read and write as a child, and signed with a shaky cross at the time of her marriage to James in 1836. However it would not have been surprising if she learned to read following her marriage, since methodists encouraged adult education, even taking adults into some of their schools[20]. Thus it may have been the case that Hope and her foster mother had learned to read side by side.

By 1851, the Smith household seems to have become something of a refuge for disadvantaged young women. On the census of that year, James, Sarah and seventeen-year-old Hope are also living with Selina Whitcombe (aged 23) and Eliza Robbins (aged 28), the latter of whom had a one-year-old daughter named Jane. Selina was an orphan, born in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, who seems to have also been from a travelling family. The origins of Eliza and her daughter are less clear, and how long any of them had been living with the Smiths is not clear. Selina would continue to live in the area, and she and Hope appear to have remained friends.

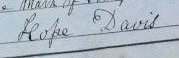

Selina Whitcombe apparently also became close with James Smith's grandson, Thomas Smith. The two were married at the Methodist Chapel in Stroud on 4 July 1852, with Hope signing as one of their official witnesses. This is our earliest example of Hope signing her own name. She signs as "Hope Davis", indicating that she now considered this the formal version of her name. The 1851 census marked the final time her name is known to have been recorded as "Valentine".

Two weeks after Thomas and Selina's wedding, Hope's foster father James died of old age.

Marriage and motherhood 1856-1908

It is not entirely clear how Hope came to know her future husband, Charles Philpotts, who was roughly two years her junior. They both lived within the parish of Minchinhampton, but the population of the parish was several thousand, and it so happened that Charles and his family lived at the very opposite end of its bounds, in the hamlet of Besbury over a mile and a half away. They were both woollen cloth workers, but the district was so dotted with mills it is unlikely they worked at the same one, and since Hope had been raised a Methodist they are unlikely to have met at the parish church. None of Charles's close relatives are known to have been Methodists, and even if he had chosen to convert he is more likely to have belonged to the Brimscombe congregation, which was much closer to Besbury than Littleworth. It is possible they were introduced through Charles's cousin Ann Denning. Ann, whose mother had died young, had spent at least part of her childhood in Charles's household. In 1861 she was lodging with a couple coincidentally named Davis, who lived a couple of doors away from Hope's aunt and foster mother Sarah. If Ann had been with the Davises for several years, then Hope would also have been her neighbour, and they may have bonded over the similarities in their childhoods. Ann may then have introduced Hope to her cousin Charles, but this is only speculation.

Hope and Charles married on 5 October 1856 at Minchinhampton parish church. The decision to marry there and not the Wesleyan chapel probably indicates that Charles was not a Methodist. Thomas Smith acted as one of the official witnesses, just as Hope had done for his wedding four years earlier. The second witness was Fenning Parke, Minchinhampton's long-serving parish registrar. This should not be taken as evidence that Hope or Charles knew him on a personal level, as it was extremely common for registrars to act as witnesses. Hope's father's name is recorded accurately as Jonathan Davis, but his occupation is left blank. This suggests that Hope either did not know of any "honest" profession her father had held, or was perhaps too embarrassed to reveal that he had been a tinker, a word almost synonymous with "gypsy"[Note 4].

Following their marriage, Hope and Charles settled in Amberley village, the largest of the cluster of villages which includes Theescombe and Littleworth. Hope gave birth to their first and only child in August 1857, ten months to the day after the wedding. He was named James William, his first name probably being a tribute to Hope's foster-father James Smith, and William being the name of one of Charles's brothers. At eight weeks old little James was taken for baptism at the Wesleyan chapel. Whether the lack of any further children was due to medical reasons, or a choice made by Hope and Charles, is impossible to tell.

Charles was at this point working as a general labourer, meaning he probably did casual agricultural work for hire. This apparently did not bring in enough income or was not reliable enough for Hope to be a full-time mother and housewife, and she was back in work again at least as early as 1861. Rather than going back to a woollen mill, she became a walking stick polisher, which involved applying lacquer to walking sticks. This would have been done as piece work from home, meaning she could take care of James and continue working. Manufacture of walking sticks and umbrella handles was a major industry in the Stroud district in the latter half of the nineteenth century, making use of local beechwood and repurposing disused cloth mills[22]. Hope had perhaps been introduced to this work via members of Charles's family, since his uncle Stephen Philpotts and Stephen's sons worked as umbrella and walking stick makers, with Stephen's two daughters also working as walking stick polishers.

During the 1860s Hope, Charles and James moved a short distance to the village of Littleworth. This placed them closer to Hope's aunt and foster mother Sarah, who had lived alone in Littleworth since James Smith's death. At some point Charles got a job working at a chemical factory in Woodchester, and Hope continued working as a walking stick polisher. Meanwhile James began attending the same Methodist Sunday school that Hope had attended twenty years previously. Whether James also attended Littleworth's Wesleyan weekday school is unknown, since only the Sunday school's records survive. In 1865 both Hope and Charles acted as witnesses at the wedding of Charles's brother Joel Daniel. Whereas Charles had signed his own marriage record with a cross, he was now apparently able to write his name. Perhaps Hope had encouraged him to learn to read and write as an adult, following the example of her aunt Sarah.

Another example Hope seems to have taken from her foster parents is that of opening her home to others in need. On the 1871 census she, Charles and James were living with an 11-year-old child named Mary Ann Turner. Mary Ann was purportedly born in Little Dean in the West of Gloucestershire, but no trace of her can be found either before or after this single census record[Note 5]. Presumably she was either an orphan or her family were unable to take care of her for some other reason. The name Turner does not appear among English Romani traveller families, so it is unlikely she had a similar background to Hope. The snapshot provided by the census cannot tell us how long Mary Ann was in the Philpotts household, meaning she could have been anything from an overnight visitor to Hope and Charles's foster child.

That same year, Hope's aunt and foster mother Sarah began suffering with paralysis. Although we don't have any confirmation of her whereabouts beyond that she remained in Littleworth, since she would have been unable to continue looking after herself it seems likely to me that she moved into Hope's household. She died in October 1873, at the age of 77. Charles reported the death to the registrar and is recorded as having been present at the death, although since this is only recorded for the reporting individual it does not rule out Hope having also been present when the woman who raised her passed.

It was probably around this time that Hope's son James began working as a wood turner, perhaps working for the same sawmill who employed Hope. In 1877 James married Jenny Smith. Jenny was no known relation to Hope's foster father, but her stepfather Richard Burford was from a Methodist family, some of whom had been baptised at the Littleworth chapel, so it may have been through this link that she came to know James. The official witnesses to their wedding were Selina Ann Smith and John Rodway, the daughter and son-in-law of Hope's friends Thomas Smith and Selina Whitcombe. James and Jenny remained close to Hope and Charles, setting up home at Pinfarthings, another small village clustered around Amberley. Hope became a grandmother in 1878, when James's first child William James Philpotts was born.

One day in early 1880 Hope returned home to find that some money she had left on the table had gone. The thief turned out to be 33-year-old James Horwood, who lived nearby. He was caught thanks to a trail of footprints leading back to his house, and sentenced to a month's imprisonment[23].

By the time of the 1881 census Hope and Charles had taken in an 88-year-old widow named Hannah Prince, who had been a neighbour of theirs while her husband was alive. She died later that same year. By 1885 Hope and Charles had moved to St Chloe Green[24], a row of houses alongside the green of the same name situated at the northern end of Amberley. Around 1888 their son James moved away from the Stroud district altogether, having taken a job with a large furniture-making company in Gloucester. It cannot have been easy for Hope to see her son and grandchildren depart for the city, since she now had no living relatives nearby besides her husband. There is no evidence that she had ever been especially close to anyone in James Smith's family, with the exception of her step-nephew Thomas.

Hope by now had six grandchildren. The third of these - James's first daughter - was named Elizabeth Amelia. It may be coincidence, but it is my suspicion that the middle name Amelia was given at Hope's request, in honour of the mother she had never known.

On the 1891 census Hope and Charles had another elderly lodger named James Radcliffe, who like Hannah Prince had also been a neighbour prior to being widowed. He may have remained with them for some years, as he died in 1896. It appears that by now Hope had stopped working, since she has no occupation listed. She also seems to have lost track of her age somewhat. Both she and Charles occasionally lost a year or two off their actual ages at each census, but Hope was consistently marked as being one year older than Charles (which was not entirely accurate, since she was actually a little over two years his senior). By 1891 this has been reversed, with Hope stated to be 52 and Charles 53. They were in fact 57 and 55 respectively.

By the time of the 1901 census Charles was also retired, and they were living on parish relief. They no longer had a lodger. Curiously, whereas Hope's place of birth had previously always been given as Devonshire, on this census she is (accurately) stated to have been born in Somersetshire. This suggests Hope may have received some new information regarding her birth, but if so, it is hard to say who this could have been from. None of her aunts or uncles were still living (Sarah had in fact been the longest-lived of the Hunt siblings). She did however have numerous living cousins on the Hunt side, several of whom were older than her and may have remembered her birth.

Hope and Charles became great-grandparents in September 1903, when their second-eldest grandson Charles Herbert's daughter Lillian was born. Lillian sadly only lived for three days.

Final years 1908-1916

In September 1908 Charles was suffering from bronchitis. His condition seems to have been severe enough that it was assumed he was close to death, as James had travelled down from Gloucester to be with his father at the end. He died on 15 September, with the final cause of death being certified as cardiac failure. James probably stayed with Hope for a few days more, as he reported the death to the registrar on the nineteenth.

Now in her seventies, Hope was taken to live with James and his family, at his house on Clifton Road in Gloucester. It was probably quite jarring for Hope, having lived her entire life in the countryside, to now find herself near the centre of a busy, growing city. Her three eldest grandchildren had moved out of the family home, and another had died, meaning the household now consisted of James, Jenny, their children Bertie (b.1883), Arthur (b.1887), Fred (b.1889), James (b.1892), Sidney (b.1894), Jack (b.1896), Nellie (whose middle name was Hope; b.1898), and Doris (1901), and their foster daughter Edith Pendry (b.1893). Edith, who had a learning disability, had been the illegitimate daughter of a local teenager. It seems that James was continuing the family tradition of offering a home to disadvantaged neighbours. As the house only had five bedrooms, Hope would almost certainly have had to share with one or more of the grandchildren.

Although it does not appear that Hope's grandchildren had as strict a Methodist upbringing as she did, the family were still somewhat loyal to that denomination, and were known to attend events at a Primitive Methodist chapel a few minutes' walk from their home. Hope's grandsons James and Jack had helped organise a waxworks exhibition at a fête there in 1907[25], and Bertie played gramophone selections for a fundraising social evening there in 1912[26].

The 1911 census gives us another glimpse into Hope's knowledge of her birth family. This was the first census on which heads of household were responsible for completing the schedule themselves, and James meticulously followed the instructions which included listing both the place and county of each person's birth. And so, instead of simply a county name, Hope's birthplace is now given as "Ramsdon, Somersetshire". There is no such place as Ramsdon in Somerset, but there is a Ramsden in Oxfordshire, and it happened to be one of the more frequent stopping places for both the Hunt and Davis families. Both families had been there for the wedding of Hope's uncle Jonathan Hunt to her grandaunt Rosa Davis in 1825. Her cousins Charles Hunt (son of her uncle William) and James Hunt (son of her uncle Thomas) had been born there in 1838 and 1845 respectively. It was also quite close to Fulbrook, where her uncle Thomas had settled with his family in the late 1840s, making him the closest of any of the Hunt siblings besides her aunt Sarah, and the only other Hunt sibling to give up travelling. We can assume then that Hope heard enough stories about her family's travels - and perhaps met members of her extended family - for the name Ramsden to have stuck in her memory.

As the years went by the house on Clifton Road would have begun to empty out. Bertie, Fred and Arthur married and moved out in 1909, 1911 and 1912 respectively. When war broke out in 1914, the three remaining sons - James, Sidney and Jack - would enlist in the armed forces, shrinking the household down to just Hope, James, Jenny, the two younger daughters, and Edith.

Hope would not live to see the end of the war. In April 1916 she developed bronchitis, as Charles had eight years earlier. She died after seven days of illness, at the age of eighty-two. As well as her son and eleven surviving grandchildren, at the time of her death she was survived by six living great-grandchildren.

Legacy

If Hope had any identifiable lasting influence on the family, it was in passing on her stepfather's James Smith's Methodist faith. Aside from the grandchildren's aforementioned attendance of the local chapel, a few of them were married in Methodist places of worship, and at least two great-grandchildren (a daughter of Bertie and a son of Fred) received Methodist baptisms. The fact that not all the children chose a Methodist wedding is not necessarily a good indicator of their loyalty to the denomination, when we consider that Hope herself married at the local Anglican church. It is not known if this association with Methodism continued for any members of the Philpotts family. It did not do so in my branch of the family.

What is more fascinating to me, is the question of how much successive generations knew of Hope's birth family and, if they knew, how they felt about it. I feel it is more or less certain that James would have been aware, with his great-aunt Sarah still being alive until 1873, and his attempt to accurately record her birthplace on the 1911 census. But did the grandchildren, who would surely have known Hope quite well in her final years, have any inkling? And if they did, had it become something shameful, or something exotic to be romanticised, or perhaps even a cautionary tale - "don't steal, or you'll end up like your great-grandpa!"? Did Elizabeth Amelia know anything of her great-grandmother, for whom she was given her middle name?

My gut feeling is that at least some knowledge of this aspect of the family's history made it into that generation of grandchildren, but perhaps no further. The identity of Hope's parents is not immediately obvious from the available records, and I was only able to make the discovery thanks to DNA testing. It was a surprise to me and my immediate family, and we are not aware that any hint of Hope's Roma heritage passed into my grandparents' generation. Whether through stigma, shame or a simple lack of interest, the true story of Hope's origins and the tragic events that shaped the course of her life were almost lost to history.

Notes

1. She was baptised on 5 January 1834[1]. Dates of birth are not frequently recorded prior to legal registration that began in 1837, but in cases where they are known it generally appears that children in the Davis and Hunt families were typically baptised within a few days of birth. See for example Hope's maternal aunt Ann Hunt who was baptised at one day old in 1792, or her paternal aunt Susanna Davis whose age at death was seven weeks and was buried seven weeks to the day after her baptism. They may have followed the tradition of baptising on the first Sunday after the birth, which would put Hope's birth date between 29 December 1833 and 4 January, or maybe the morning of the 5th itself.

2. Various sources agree on Romani births taking place away from the usual living area, as pregnancy and childbirth fall under what is considered mochadi (impure)[2], although I have not been able to find any contemporary descriptions of Roma births in England from around the time of Hope's birth. A 1923 newspaper article on "Gypsy Birth Customs" states that "In bygone times a special tent was set apart for the child-bearer, and this was destroyed so soon as its use was at an end"[3], and in the month of January this would certainly seem to be a preferable option to an open-air birth. However an account from 1904 tells of a Roma child born "under the stars on the grass" in December[4]. It is also possible that the birth took place inside a building, but I think this is unlikely. Emborough was a tiny village consisting of a few scattered farms, with no inns or boarding houses, and such was anti-Roma sentiment at the time I am not confident that any of its inhabitants would extend their hospitality even to a heavily pregnant Romani woman.

3. On each of the three surviving records of Hope's birth name it is spelled differently. On her baptism it is "Florentine", on the 1841 census "Follentine" and the 1851 census "Valentine". I have used the spelling Valentine here because that is the spelling most consistently used for her relatives of the same name, including the aunt who she is presumed to have been named after.

4. In a sample of British newspaper stories between 1800 and 1849 containing the word "tinker" in reference to a person, well over half of them also note that the person was a traveller or "gipsy", so I feel it is safe to assume the association was already well-established by the time of Hope's wedding[21].

5. To save anyone the trouble of repeating my fruitless research, I have confidently ruled out the following leads - Mary Ann Turner born 1859 East Dean; Mary Ann Gurner born 1859 Little Dean; Mary Ann Turner who married John Davis in the Stroud district in 1878; Mary Ann Turner who married Charles Rowlands Smith in Rodborough in 1892. All of these Mary Anns appear in other records that prove she cannot be the same Mary Ann Turner who lived with Hope in 1871.

References

1. Emborough parish baptism 1813-1914, Somerset Archives & Local Studies

2. Romani Customs and Traditions: Birth, rozvitok.org; accessed 30 July 2025

3. London Daily Chronicle, 14 Jun 1923

4. Daily Express, 22 December 1904

5. Cressy, David (2018): Gypsies, Oxford University Press; p72

6. Ibid; p235

7. Hoyland, John (1816): A Historical Survey of the Customs, Habits and Present State of the Gypsies

8. Cressy, op. cit.; p171

9. Stroud and Dursley Methodist Circuit, list of members 1791-1828, Gloucestershire Archives D3187/1/3/6

10. Stroud and Dursley Methodist Circuit, Littleworth Sunday School monthly book register 1839-1863, Gloucestershire Archives D3187/2/20/5

11. Wesley, John (1744): General Rules of the United Societies and General Rules of the Band Societies

12. Cressy, op. cit.; p170-172

13. Cheltenham Chronicle, 5 Jul 1838

14. Best, G.M. (2012): A historical perspective on Methodist involvement in school education after Wesley, Methodist Church

15. A Dictionary of Occupational Terms Based on the Classification of Occupations used in the Census of Population, 1921, His Majesty's Stationery Office 1927

16. Lipson, E (1921): The History of the Woollen and Worsted Industries; p210

17. Inchbrook Mill, Nailsworth, Mills Archive Trust; accessed 9 August 2025

18. Dyehouse Mills, Woodchester, Heritage Gateway; accessed 9 August 2025

19. Dame School, Victorian School; accessed 9 August 2025

20. Best, G.M. (2012): Education from a Methodist perspective, Methodist Church

21. Searches carried out on findmypast's newspaper archive 10 August 2025

22. Mills, Stephen (1996): Stick Manufacture in the Stroud Valleys, printed in Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1996; p35-41

23. Gloucestershire Chronicle; 21 February 1880

24. Register of Persons Entitled to Vote for the Mid or Stroud Division of the County of Gloucester 1885-6; Gloucestershire Archives

25. Gloucester Journal, 16 Mar 1907

26. Gloucester Journal, 13 Jan 1912

To go back to the Philpotts-Shipton tree, click here