Matilda Shipton c.1820-1907

Early Life (1820-1840)

Matilda Shipton was probably born in late 1820 or early 1821 in or near the village of Shortwood, near Nailsworth in Gloucestershire. She was the second-youngest child of William Shipton and Jane Horwood. No baptismal record survives for Matilda (or any of her siblings) since her parents were adherents of the Baptist faith[Note 1], and as such she would not have been baptised in infancy, and there was no other legal means to officially record childbirths at the time[13]. Her approximate date of birth is assumed from later records[Note 2].

As far as can be told, Matilda had four older siblings at the time of her birth – John (b.~1803), Richard (birthdate unknown), Samuel (b.~1811), and Mary (b.~1814). She may have had more siblings, but without any recorded births or baptisms there is no way of telling. These four are all attested from later records. A younger brother, William, was born in about 1823. William would be described as a "cripple" on the 1851 census, but it is not clear whether this was an acquired disability or one he was born with.

The family was not wealthy. Matilda's father was an agricultural labourer, meaning he would have been hired temporarily by local farmers as and when work was available[1], although the family may also have owned or rented plot where they could grow their own fruit or vegetables[Note 3]. Matilda's older brothers would also be described as labourers in early adulthood, and the eldest would have already been working at the time of Matilda's birth. Matilda may have had a little education at a Sunday school, but not enough for her to be confidently literate as an adult.

The household in which Matilda grew up may also have been a violent one, with her eldest brother John in particular apparently having a short temper. The earliest evidence of this is from 1820, when at the age of 16 he was arrested and charged with beating someone about the head with a stick[4]. The context of this act however is likely also indicative of the family's poverty, as the man John assaulted had caught him in the process of attempting to poach rabbits, something which was commonly done by the rural poor as a desperate means to put food on the table[5], although for skilled poachers who sold their catches to others it could be a means of making a living in itself[59]. Later the same year John was charged with stealing poultry, but was released due to lack of evidence, and in 1823 he was convicted of killing rabbits, for which he served six months in Horsley House of Correction.

Matilda's father died during her childhood or early adulthood, possibly in 1831[Note 4]. By this point Matilda was probably in work. We know that as an adult she was a cloth worker, so it is likely she began as a child in one of the district's many woollen mills, doing a job such as carding (separating fibres) or piecening (loading yarn onto the frame)[6]. The nearest mill to where Matilda is known to have lived appears to be William Ashmead's flock mill in Newmarket, later known as Upper Mill[7]. Matilda's brother Samuel lived next to this mill in 1841. However there were so many mills in the Stroud district, some of them tiny and barely recorded, that this is by no means the only candidate.

The hours of work would have been incredibly long, perhaps up to fourteen hours a day when she first began. The Factory Act of 1833 prevented those under eighteen from being employed more than twelve hours a day or sixty-nine hours a week. For those aged thirteen or younger, the daily maximum was nine hours[8], a regulation which Matilda would have just missed out on. The pay in the Stroud District mills was abysmal, to the extent that the governor of Horsley Gaol remarked in 1840 that imprisoned textile workers regretted leaving since they could no longer rely on regular meals[9].

Throughout this period Matilda and her family were probably attendees at the Baptist Meeting House. It was said to have held the largest rural Baptist congregation in the country, with around 650 regular adult members and 270 Sunday School attendees as of 1851[10]. In 1835 Matilda's cousin Isaac Brinkworth (1796-1881; son of her paternal aunt Mary) began working as the Meeting House sexton, a position he was said to have taken very seriously[11]. Cousins on both the Shipton and Horwood sides are uniformly lacking infant Church of England baptism records, suggesting that the entire extended family were Baptists. Matilda is at some point likely to have undergone a "believer's baptism" at the Meeting House, probably around the age of nineteen, although it is difficult to gauge what the typical age was in that time and place[14].

For the Shiptons however this adherence to Baptism may have been a case more of opportunity than conviction. Horsley, their Anglican parish, covered quite a large area and its church was almost a mile from Shortwood. Although the Shortwood Meeting House was phenomenally popular, with attendees scattered all around the district[10], it also happened to be the Shiptons' nearest place of worship. Some of them would apparently turn their backs on the non-conformist congregation, Matilda's brothers John and Richard being baptised as adults at Horsley parish church in 1837 and 1843 respectively, the former on the day of his wedding[16].

This shift away from the Shortwood congregation was mirrored by a literal move away from Shortwood for several of Matilda's siblings. Her sister Mary became pregnant by a travelling hawker named Henry Harding, and gave birth to a daughter named Jane in about 1836. She married Henry in Bristol the following year, and accompanied him on his travels. Matilda's brothers John and Samuel also married in 1837. John began working as a travelling cutlery salesman. In the following decade Samuel relocated to Glamorgan, part of a wave of migrants attracted by job opportunities in the Welsh coalfields. Richard's movements are much harder to pin down. Banns of marriage between him and Ann Longstreet were called in 1838, but no subsequent ceremony record can be found. A Private Richard Shipton of the 58th Regiment of Foot stationed in Scotland in 1841 may be him[17]. He was in Horsley for his Anglican baptism in 1843, but cannot be found on any later records. Matilda and youngest sibling William are the only two known to have remained in Shortwood.

Adulthood and First Marriage (1841-1858)

At the time of the 1841 census Matilda and her mother are living in a house called High Wood Cottage, alongside her sister Mary, brother-in-law Henry Harding, and five Harding children (the eldest of whom, 10-year-old Caroline, was from Henry's first marriage). Henry was still listed as a licensed hawker and it seems the Hardings divided their time between Horsley and Bristol, where several of the children were born. Youngest sibling William was now apprenticed to a shoemaker in Nailsworth. I have not been able to find out if High Wood Cottage still exists, but as the name suggests, it was probably on the wooded ridge overlooking Shortwood from the north. The ordering on the census schedule seems to confirm this, placing the cottage between the hamlet of Kingley Bottom and the village of Newmarket. This would put the family on the hill directly overlooking Shortwood Meeting House (see OS map excerpt below).

Options were limited for working class women in the early Victorian period, and marriage could be as much a safeguard against poverty as a matter of love[18][19]. Matilda's husband-to-be was a widower twenty years her senior by the name of Joseph Smith. Another long-time member of the Baptist congregation, Joseph had been widowed since 1826[20], and his son George (born 1823) appears to be the only child from his first marriage[21]. His first wife, Sarah Ricketts, may have been a cousin of Matilda's, since Matilda's maternal grandmother also had the maiden name Ricketts. Once again a lack of baptism records in the extended family prevents us from confirming this.

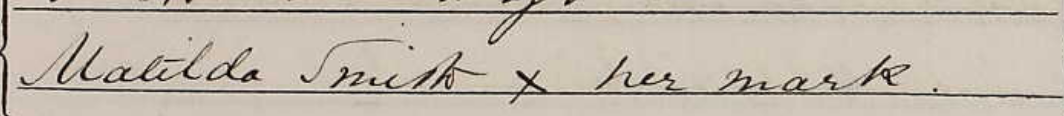

Joseph and Matilda's wedding took place at the Baptist meeting house on 27 August 1843. Marriage at the Meeting House, or any other non-conformist chapel, had only recently become a legal possibility with the passing of the Marriage Act of 1836[22]. The official witnesses were another couple getting married on the same day – Matilda's cousin John Smith Cloudsley (son of her maternal aunt Deborah), himself a widower marrying for the second time, and Sarah Teakle. Sarah's sister Hannah would go on to marry Joseph's son George the following year. John Smith Cloudsley's parents were next door neighbours of Joseph in Shortwood village, so clearly both community and congregation were extremely close-knit.

Matilda's first child, Thomas, was born in or around March 1844. This makes it quite likely Joseph and Matilda's relationship was a sexual one prior to their marriage. This was not at all uncommon[23] nor even particularly frowned upon so long as the couple married before any child was born[42]. It was in fact in this regard that Matilda stood out among her siblings. As previously noted, Mary's first child was born around a year before she married, whereas John's only known child Charles was born roughly a decade before he was wed. In 1834 Samuel was fined for disobeying an order of bastardy (court-mandated payments to the mother of an illegitimate child he had fathered[24]), but the details of his case are not known[Note 5].

Matilda would now almost certainly have left her job at the local mill to focus on work at home, probably juggling childcare, domestic chores, and assisting Joseph in his work. Joseph was a weaver, and a description on the census of Matilda being an assistant suggests that he was working at home on a handloom. The Industrial Revolution had dealt a huge blow to weaving as a cottage industry over the past century, and had forced many of Stroud's weavers to take up work in the mills[25]. However a contemporary report on the woollen industry from 1859 reveals that, in contrast to cotton weaving which could be done much faster on a power loom, the more delicate nature of woollen manufacture meant that skilled handloom weavers could and did continue to work from home[26]. They would not produce finished clothing themselves, but would instead take payment to provide woven cloth to fulling and dying mills, in at least some cases being employed directly by the mill. These weavers were reportedly always men, but the same source shows a large number of women working outside the mills as burlers (picking burrs and other imperfections out of the fabric)[27], so this may have been something Matilda did.

The family home was in Shortwood's Old Workhouse, which had probably become disused in 1836 when Horsley joined Stroud Poor-Law Union[28], and now housed around eight families. The household probably included Matilda's stepson George, who worked as a labourer and was nineteen at the time of the marriage, and Joseph's mother Hester. Hester was living with Joseph at the time of the 1841 census, and is not there in 1851, but her year of death is not known. There is no indication of how well Matilda got along with George, or whether there was any awkwardness or resentment due to them being them being almost the same age. George married less than a year after Matilda and Joseph. He and his wife Hannah moved briefly to Wales in the late 1840s, then returned to the Shortwood area for a few years before emigrating to Australia where they became devout members of the Churches of Christ. George's obituary in 1903 describes him as "a kind and loving man" who was "fond of his bible and read it constantly"[29].

Matilda had a second child, Sarah, born in about 1846. If there were more children born in the late 1840s, their names have not been recorded and they must have died in childhood. Once again the Baptist convention of not baptising children at birth means that any child who was no longer alive by the time of the next census is invisible in the available records. In theory any child born from 1837 onwards should have a birth certificate, but the process of registration was poorly understood by the public and seldom enforced[62]. Certificates do not appear to exist for Thomas or Sarah, leaving open the possibility of other undocumented children in the family who did not survive long enough to appear on a census. Matilda and Joseph's next known child was born in 1851 and named James.

James became Matilda's first and only child to be baptised in the Church of England. This took place at Horsley parish church on 31 August 1851, the same day as his aunt Mary's eighth child, Hannah Harding. The Harding children were all baptised in the Church of England, albeit some of them a few years belatedly, as were the children of Matilda's brother Samuel16. While the other Shipton siblings were gradually switching their allegeince to the established church, Matilda seems to have been less so inclined, perhaps because she was the only one to have married within the Baptist congregation. It is even possible that James was baptised without his parents' consent or knowledge; the baptism of one of Mary's children on the same day suggesting that she may have taken James to get baptised whilst baby-sitting for her sister. James also appears to have been the first of Matilda's children whose birth was officially registered and thus has a birth certificate. James must also have died young, as he does not appear on the 1861 census.

By the time of the 1851 census, Matilda's brother William was now living with her, Joseph and the children. He may have moved in after the death of their mother Jane in 1850. Wiliam's entry on the census describes him as a cripple and a pauper, so if this was indeed an acquired disability it perhaps prevented him from working. It possibly also cut short his teenage apprenticeship to a shoemaker, since there is no indication that he ever worked in that trade as an adult.

Elsewhere in Matilda's family, we have more evidence from this period for her brother John's tendencies towards violence. According to testimonies repeated in the local news, on 28 December 1848 John was quarrelling with his wife Deliah, when Deliah's brother Edmund Risby stepped in, and he and John got into a "tussle". Another man by the name of Gleed tried to separate them, whereupon John took a sword down from the wall and began beating Edmund about the head and shoulders with it. The sword was clearly either blunt or John had used the flat of the blade, but Edmund nevertheless received injuries serious enough that he had to see a surgeon. Apparently there had been some animosity between John and Edmund over some money left to them by a deceased relative[30]. John claimed he had only taken down the sword in self-defence. Incredibly, the court took his side and he was found not guilty[31].

Matilda had one more child in the 1850s, who was named Joseph like his father, and was born in 1853. Like James he has a birth certificate, but he was not baptised as an infant. A report from 1872 states that Joseph Jr. was "very deaf". This may have been the result of an injury or illness as it is not mentioned on either the 1861 or the 1871 census. However the census was only supposed to record if someone was "deaf and dumb" (an archaic term referring to someone who was deaf and did not use vocal speech[32]), the same report suggests Joseph did communicate with his voice. Early dialects of British Sign Language existed, but signing was actively discouraged even in some schools for deaf children, which in any case were more commonly found in urban areas[33]. Being from a poor rural background young Joseph likely had little-to-no contact with other deaf people, and possibly relied upon lip-reading and gesture to understand others.

Widowhood and Second Marriage (1858-1869)

Matilda was widowed on 22 October 1858. The cause of Joseph's death was described as "chronic disease of the stomach". This could indicate some form of gastric cancer, which was still poorly understood[34]. Since he had been unwell for some time, this had probably affected his ability to work and made the family's financial situation extremely precarious. His death was reported to the registrar by Matilda's sister-in-law Deliah, the wife of her brother John. Deliah was not a near-neighbour like some of Matilda and Joseph's other relatives - she lived in Horsley village about a mile away - but the fact that she was present at the death and took responsibility for reporting it indicates she was probably close to her in-laws, and had perhaps offered to see the registrar so as not to trouble Matilda with the task during her grief.

Matilda doubtless would have struggled without her husband's income. Like many lower-class Victorian widows, she began working as a laundress, washing the clothes of wealthier locals in exchange for a few pennies[35]. Eldest child Thomas found work as a baker's assistant, and Sarah in a woollen mill. Her brother William, still part of the household, was also now in work as a carter.

Less than a year after Joseph's death, Matilda became pregnant. Her daughter Jane (known as Jenny) was born on 21 March 1860. Jenny's father was not named on the birth certificate, although this does not necessarily mean Matilda did not know who he was. It seems that either Matilda had entered into another relationship (one which may even have begun whilst Joseph was still alive), or was engaged in sex work. A second illegitimate child named Elizabeth was born in March 1863. The fact that Matilda remained unmarried does support the theory that she was a sex worker. This was not an entirely uncommon means of boosting the household income for women in her position[36], albeit one which was the subject of increasing societal condemnation and government intervention[37]. An alternate possibility is that Matilda was having an affair with a married man.[Note 6].

While Jenny was presumably named after Matilda's mother Jane, the only known Elizabeth in Matilda's family was her aunt Betty Shipton, about whom very little is known. On the census, Matilda's daughter Elizabeth would be described as an imbecile. This is an obsolete psychiatric term referring to someone with a moderate learning disability, with a supposed "mental age" of three to seven years[38]. For many mild or moderately learning disabled children of Elizabeth's generation, their disability was only realised with the introduction of compulsory state schooling in 1870, when their abilities were compared with other children of the same age and class background. Segregated schooling for these individuals did not appear until 1875. Children whose learning disabilities were more apparent could be sent to so-called "idiot asylums", many of which were run charitably and were thus an option for working class families[39], but this clearly did not happen with Elizabeth since she remained in Matilda's household.

Matilda did eventually remarry, on 11 September 1866. Her second husband was Richard Burford, another local weaver. His sister Harriet was a resident of the Old Workhouse at Shortwood, so it is probably through her that he and Matilda came to know each other. A bachelor eight years younger than Matilda, Richard had lived in nearby Newmarket as a young man, although on the 1861 census we find him lodging some eight miles away in the parish of Kingswood. If Matilda had been engaged in sex work during her widowhood, he might have been one of her clients before they chose to settle down. Whatever the case, he obviously saw no shame in marrying a woman with two illegitimate children, and the circumstances would seem to indicate that he and Matilda truly enjoyed each other's company.

Richard does not appear to have belonged to the Baptist congregation, although he and most of his siblings had all been baptised in one go at an Anglican church in 1840 when Richard was eleven, suggesting perhaps another case of a family returning to the established church having previously been non-conformists. The eldest sibling, Enoch, had been baptised at Littleworth Wesleyan chapel, as were several of Richard's cousins[40], so the Burfords presumably were or had been Methodists. Matilda and Richard's wedding took place at the parish church in Horsley, with Matilda's brother William and Richard's aforementioned sister Harriet acting as witnesses.

It is perhaps possible that Matilda and Richard's relationship had been going on for several years and that he was the father of Jenny and Elizabeth. I find this unlikely in the case of Jenny[Note 8], but plausible and even somewhat likely in the case of Elizabeth, not least because Elizabeth was the name of Richard's mother. Both Jenny and Elizabeth have the surname Burford on the 1871 census, although I suspect this was probably a small lie Matilda told the enumerator to hide the fact that they were illegitimate. Both daughters have the surname Smith when they next appear in public records. Whether or not Jenny grew up believing Joseph was her father is another matter.

Once married, Matilda and Richard lived at Wag Hill, a small hamlet slightly to the west of Shortwood (see map excerpt). They may have lived with or close to Richard's brother Jacob, who was resident in Wag Hill in 1861.

Matilda's son Thomas married Mary Ann Howell in 1867. Neither of the witnesses were from his side of the family, and following their marriage they lived at Wallow Green. about half a mile away towards Horsley village. Neither of these facts are necessarily significant on their own, but later events would show that some tension had been developing between Thomas and the rest of his family[Note 7].

Second child Sarah disappears from the household at some point between the 1861 and 1871 censuses, and cannot be found living anywhere else. Her getting married would normally be the most likely explanation, but there are no obvious candidates among the records of Sarah Smiths marrying in the Stroud District, nor are there any married Sarahs born in Horsley anywhere on the 1871 census who are the right age. Of the registered deaths of Sarah Smiths in the Stroud district during the period in question only one, in 1863, cannot be ruled out by comparison with a parish burial record. If this is not her, another possibility is that she married and then died under her married name. Alternatively, she may have emigrated. Matilda's stepson George is far from the only Horsley native to have set sail for Australia[44], and other known émigrés include a brother of Richard Burford, and John Shipton's battered brother-in-law Edmund Risby[45].

Matilda's marriage to Richard was tragically brief. He died at home on 29 August 1869, with Matilda by his side. The cause of death was described in rather vague terms as "natural decay from gradual failure of vital powers", which seems to indicate some kind of progressive illness which physicians of the time did not understand. It definitely suggests that like Joseph Smith before him, Richard had been suffering and weakening for some time prior to his death.

For all that he was in the family briefly, Richard was probably the closest thing to a father Matilda's youngest children Jenny and Elizabeth ever had. A clue that he may have been remembered him fondly is that Jenny's eighth son Sidney would be given the middle name Richard, which could have been a tribute to Jenny's departed stepfather. It may even have been thanks to Richard that Jenny met her husband-to-be. While it is difficult to gauge the exact extent of the Burford family's association with Littleworth Wesleyan chapel, Jenny's future mother-in-law was the adoptive daughter of that chapel's preacher.

Later Life (1869-1907)

Widowed once again, finances would have become strained once more. At the time of the 1871 census Matilda's address is in Lophorn, which was a tiny hamlet of three households to the west of Shortwood, no longer extant. Matilda, her son Joseph and brother William (who still lived with her) are all listed as agricultural labourers. Daughters Jenny and Elizabeth would have been legally required to attend a school since the previous year[46]. Elder son Thomas was still at Wallow Green, although he is inexplicably absent from the 1871 census, his home occupied by just his wife Mary Ann and their one-year-old son John. Earlier in their marriage Thomas and Mary Ann had had a daughter named Sarah Ellen, who was probably Matilda's first grandchild, but she had sadly died in 1870 at the age of two.

Thomas was in financial trouble of his own. He had borrowed several amounts of money from his mother, and Matilda did not trust him well enough to pay it back, and so was keeping hold of his watch as a pledge. One Sunday in September 1872 he turned up at her house offering to return a little of the money and demanding to have his watch back. Matilda however refused to give it up until all the debt was repaid. Thomas went upstairs to take the watch and, according to the ensuing courtroom testimonies, when Matilda tried to stop him he flung her on the bed and tried to choke her. Nineteen-year-old Joseph came to her defence and was able to get Thomas off her. Matilda then sat on the box where the watch was kept, but Thomas threw her to the floor, smashed the box open and took his watch. Joseph said he would go to ""Lawyer" Smith", presumably a local solicitor who coincidentally or otherwise had the same surname, to which Thomas replied "then thou shalt have something to go for!". He then began beating his younger brother about the head. He claimed in his defence that Joseph had been armed with a stone hammer, but both Joseph and Matilda denied this. He was charged with an assault upon Joseph, although the judge expressed the opinion that he should have been summoned for the assault on his mother. Matilda had perhaps been unwilling to press charges against her own son. The court fined Thomas ten shillings plus costs of five shillings and six pence, which he immediately paid, apparently now having money to spare[47].

Like his sister Sarah before him, Joseph vanishes from all records at some point before the following census. All registered deaths of Joseph Smiths in the Stroud district can be ruled out as not being him, making it very likely that he emigrated. A 23-year-old agricultural labourer named Joseph Smith sailing from London to South Australia in March 1877 could well be him, although the name is of course far too common to tell.

The fates of Matilda's two illegitimate children are more well known. At the age of fourteen Elizabeth was apparently deemed able enough to spend time about the village unsupervised, although she was prone to seizures, and her learning disability would doubtless have made her very vulnerable. On 27 April 1877 her body was found in the mill pond at Upper Mill. A coroner's inquest determined she had drowned, and suggested she had probably accidentally fallen into the pond during a seizure. I can only imagine the amount of anguish and guilt Matilda must have felt following her death.

Her next youngest daughter Jenny, now aged seventeen, was in a relationship with a twenty-year-old wood turner named James Philpotts, and had become pregnant. She and James were married in August 1877, and their first child was born on the first day of 1878. On the marriage register Jenny is stated to be resident in James's home village of Amberley, so she may have already been working there in a service job.

On the 1881 census Matilda is living with Jenny and her husband in the hamlet of Pinfarthings, near Amberley. This was the furthest she had ever lived from where she was born, although still only about a mile away. After more than two decades of living with Matilda, her brother William Shipton was now lodging at the New Inn in Newmarket. Having lost so many family members to death, emigration or quarrels over money, it probably brought Matilda some comfort to be with her grown-up daughter and grandchildren. Jenny's third child and eldest daughter was born in November 1881, and named Elizabeth Amelia, her first name almost certainly a tribute to Matilda's youngest.

Matilda was now working as a charwoman – essentially a cleaner. As opposed to maids who were live-in servants, charwomen worked casually, offering their services to households on a temporary basis[48]. A colourful and presumably highly stereotyped portrait of the typical charwoman in Punch magazine said:

Her social position is not to be envied much. She is the lowest trade of domestic - even lower than the maid of all work, to whom she officiates as a sort of maid of all work herself. Mistresses have but little love for her, for she is never called in but at the last extremity, and the house is never comfortable till she is out of it.

The Punch writer goes on to suggest that charwomen had a tendency to steal from the households they worked in, and were always listening out for gossip, but were nevertheless extremely reliable and industrious in their work[49]. Whether or not any of these attributes applied to Matilda, we can probably assume they featured in the suspicions and prejudices of those who typically employed her.

In about 1888, Jenny and her family moved to Gloucester, where James had found work with a large furniture-making company. Matilda did not go with them. There is no evidence of any ill-feeling between mother and daughter, so she may have simply decided that at almost 70 years of age she would rather stay in the same area she had lived all her life. When Jenny's second daughter was born in 1898 (after an astonishing eight sons in a row), she was named Nellie Matilda Hope Philpotts (Hope being the name of James's mother).

Thomas on the other hand had three daughters, and chose not to name any of them after Matilda. Mother and son had apparently patched things up however, as it was in Thomas's household that we find Matilda on the 1891 census. This may seem surprising given that their last known meeting before this was when she was telling a court how he had brutally assaulted her, but I can imagine that they might have reconciled following the tragic death of Elizabeth, whose name Thomas did give to his youngest daughter in 1882.

It is possible however that old tensions between Matilda and Thomas were reignited. By 1901 she had moved out of Thomas's home in Rodborough and was staying in Nailsworth with a more distant relative - Martha Cloudsley, daughter of John and Hannah, the couple who had witnessed Matilda's first wedding to Joseph Smith almost sixty years prior. At the age of eighty-one, Matilda is listed as "retired washerwoman". They also lived with Martha's 15-year-old niece Alice Kirby, and a 48-year-old lodger by the name of Henry Turner. Martha had never married, and worked as a professional dressmaker, which along with any contribution from the lodger was apparently enough to support the household.

Matilda spent her final days at Stroud Union Workhouse. It is not clear how long before her death she was admitted, but it could have been anything from a matter of days to several years. What is apparent is that she was frail and in bad health, and none of her surviving relatives were able to continue caring for her. This was a not-uncommon fate for England's elderly poor in the early 20th century, with 6.3% of women and 9.7% of men in England and Wales over the age of 75 in workhouses in 1901[50]. A newspaper article from December 1907, shortly after Matilda's death, reports that the Stroud workhouse housed "125 old men, 78 old women, 15 young men, 21 young women and 37 children"[51], although it is not clear how "old" is defined in this case. If Matilda had lived a year and two months longer, she would have been eligible for the nation's first old age pensions[52].

The horrors of the workhouse are usually associated in the popular imagination with the Victorian era, but accounts of the cruelty and squalor of these institutions by no means disappeared in the twentieth century. Events at Stroud Workhouse in 1907 include an outbreak of anthrax amongst pigs kept on the premises[53], the mysterious drowning of an inmate in a washroom water tank[54], and several accounts of homeless inmates being sentenced to hard labour for refusing to perform workhouse tasks, including one man who had been made to work on a cold stone floor with thin-soled boots in the middle of winter[55]. Despite her age, Matilda may still have been allotted some light work such as sewing or gardening. Such activities were part of an incentive system whereby pauper inmates could earn a lunchtime meal in exchange for a full day's work, in addition to the standard breakfast and evening meal[56]. However, it is also possible that in her fragile condition, Matilda spent the entirety of her stay in the infirmary. This was still no enviable place to be, since workhouses supplied notoriously substandard medical care, and rural workhouses in particular often struggled to find professional nursing staff, the shortfall being made up with assistance from able-bodied inmates[57].

Matilda died on 5 November 1907, and the age of eighty-seven. The cause of death was given as "carcinoma of the liver" and "exhaustion". This was probably hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common form of liver cancer. Its symptoms include fatigue, abdominal pain, insomnia, and loss of appetite. A leading cause for its development is a chronic hepatitis infection, although alcohol use can also be a risk factor, along with a number of hereditary conditions[58].

Matilda was buried at Nailsworth parish church on 11 November[60]. The location is probably due to its being her last parish of residence prior to entering the workhouse, which suggests she had lived with her cousin Martha up to that point. That she was not buried in workhouse grounds indicates that her relatives were able to provide her with a private funeral[61], although it was in all likelihood a common grave, with no marker surviving today.

Notes

1. There is actually no source which explicitly states that Matilda's parents were Baptists, but I feel it is virtually a certainty given the complete absence of infant baptisms for the children and the the various associations Matilda and her extended family had with the Shortwood Baptist Congregation, detailed later in this text.

2. Matilda is 20 on the 1841 census, and her stated age increases by ten years at each subsequent census until 1891 when she gains a year with a stated age of 71, followed by 81 on the 1901 census. Her first marriage in 1843 simply states that she was "of full age" (meaning 21 or over), whereas on her second marriage in September 1866 she is stated to be 45. Finally at her death in November 1907 her given age is 87, although it's not clear how this was ascertained. Since the censuses of 1851 to 1881 all took place in March or April of their respective years (with the 1841 census taking place in early June) if accurate they would indicate a birth date between June 1820 and March 1821. The second marriage and later census records contradict this slightly, but never by more than a year.

3. On the records for Matilda's first marriage and the marriages of her siblings, the father's occupation is described as labourer, which in a rural area almost always meant agricultural work for hire. However for Matilda's second marriage in 1866 her father's occupation is listed as gardener. Despite the image this word conjures up, in the parlance of the era the growing of vegetables and berries which were sewn and picked by hand was called gardening regardless of the scale of the operation, in contrast to farming which was done with a plough[2]. So as a labourer and/or gardener he may have been a labourer for hire who worked predominently in market gardens, or he could have been a general rural labourer who also did some gardening on his own plot, although the enclosure of land by wealthy farmers was making this practice less and less viable in the early nineteenth century[3]. It is however perhaps not so surprising as it sounds, as William's brother Isaac owned enough land to be on the electoral register following the reform act of 1832[12], despite still being described as an agricultural labourer.

4. William was dead by the time of the 1841 census. No definite burial record or death record for him exists. A William Shipton whose death was registered in the Stroud District in 1838 has turned out to be someone else (a resident of Stonehouse). The only other plausible burial record to be found is from Horsley parish church in 1831. This William was apparently 65 years old, whereas ours would have been 56. It is possible his age was overestimated by next of kin, but this could be a different William Shipton (the best candidate would be a William son of Samuel and Mary born in 1769, although nothing further is known about him). If he remained a member of the baptist congregation, we would expect William to have been buried at the Shortwood Meeting House (as two of his siblings were), but no burial record can be found for him there.

5. Morrell's study was the best source I could find on the subject, and shows that nineteen was the most common age at baptism during the period 1700-1840, but it uses data from congregations in the United States only. However there are scattered mentions of believer's baptisms taking place at English Baptist chapels in England in contemporary newspapers, which do not mention age but all seem to imply if not outright state that those baptised were adults, not children[15].

5. I have checked Horsley overseers accounts 1832-1836, Gloucestershire Archives item number P181/OV/2/12, but accounts of bastardy orders were not included in them.

6. DNA testing has revealed that I am probably related to a family with the surname Cole who lived in Horsley in the mid-nineteenth century (two DNA matches link to the same family via different siblings), but the Coles have no apparent legitimate relationship to my ancestors. One of them, Jonathan Cole, was the next-door neighbour of Matilda's cousin Thomas Shipton at the time of the 1861 census. Jonathan was married and had several children, but does not appear to have been the most attentive father. In 1853 he spent seven days in jail for "abandoning his child". An earlier conviction in 1850 (for trying to rescue his brother William from police custody, the latter having committed an assault) describes him as being "of drunken and dissipated habits". He certainly sounds like a good candidate for the father of Jenny and/or Elizabeth, either through an extra-marital affair with Matilda or as one of her clients, although I would hesitate to call the mystery of Jane's father solved without some further evidence.

7. Details will appear later in the main text. However there is also a rather confusing and contradictory article in the Stroud Journal in May 1869 which reports on the civil case of Thomas Smith vs Richard Burford. Apparently one party or the other had rented a small plot of land on which to grow beans, potatoes and peas, whereupon the other, who disputed the land's ownership, had come along and pulled the vegetables up[43]. However, I believe this refers to a different Thomas Smith and Richard Burford (the names are common enough in the area), since it implies that the garden came with a house in Ebley that one party or that other lived in, whereas our Thomas and Richard lived in Horsley parish at this time.

8. I find it unlikely that Richard was the father of Jenny for the following reasons:

• It begs the question of why the couple waited so long to get married. Although it was deemed improper for a widow to remarry too soon after her first husband's death, even within the upper and middle classes it was generally acceptable for women to remarry after a two-year mourning period[41]

• Richard was living some ten miles away in Kingswood on the 1861 census, and although we have no clue as to how long he was there or whether he travelled at all it does make an ongoing relationship with Matilda seem somewhat less likely.

• Jenny would state on her marriage record in 1878 that Joseph Smith was her father (although in fairness this could have been an attempt to disguise her illegitimacy by naming a father with the same surname as her).

• There is no compelling DNA evidence linking me to the Burford family. Richard was one of ten siblings, most of whom had children of their own. Typically an ancestor this recent from this large a family would provide numerous DNA matches, but none have appeared.

References

1. Heritage Hunter, accessed 10 Jun 2023

2. https://elizabethwalne.co.uk/blog/2011-3-22-the-rise-decline-and-rise-again-of-market-gardens-html, accessed 10 Jun 2023

3. Hammond, J.L. & Barbara (1911): The Village Labourer 1760-1832, p159-160

4. Gloucestershire Prison Records, Gloucestershire Archives

5. Osborne, Harvey & Winstanley; Michael (2006): Rural and Urban Poaching in Victorian England, in Rural History 17, Cambridge University Press; p205-206

6. Lipson, E (1921): The History of the Woollen and Worsted Industries; p207

7. Baggs, A.P.; Jurica A.R.; & Sheils, J.W. (1976): A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 11, Bisley and Longtree Hundreds, Victoria County History; p211-215

8. Lipson, (1921); p209-210

9. https://www.stroudtextiletrust.org.uk/history-background-to-local-wool-industry, accessed 10 Jun 2023

10. 1851 Ecclesiastical Census, National Archives HO 129/338

11. Smythe, Frank Thompson (1916): Chronicles of Shortwood, 1705-1916, p56

12. Gloucestershire Electoral Registers, Gloucestershire Archives

13. Bebbington, D.W. (1991): The Baptist Conscience in the Nineteenth Century, Baptist Quarterly 34; p15

14. Morrell, Caleb (2021): Too Young to Dunk? An Examination of Baptists and Baptismal Age 1700-1840, published at www.9marks.org[Note 5]

15. See for example The London Packet and Chronicle, 7 December 1829

16. Horsley, St Martin, parish registers 1812-1859, Gloucestershire Archives

17. Asplin, Kevin: British Army, Worldwide Index 1841, National Archives

18. D'Cruz, Shani in Williams, Chris (ed), (2004): A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain, Blackwell, 2004; p255

19. Tilly, Louis A., Scott Joan W., & Cohen, Miriam (1974): Women's Work and European Feritility Patterns, University of Michigan; p25

20. Shortwood Baptist Chapel burials, Gloucestershire Family History Society

21. Smith family bible, shared on ancestry.com by one of his descendents

22. A Bill for Marriages in England (1836), Section 12, Parliament of the United Kingdom

23. Percoco, Cassidy (2020): Yes, They Did: Premarital Sex in (English) History, Medium

24. https://www.pricegen.com/bastardy-or-illegitimacy-in-england/, accessed 12 Jun 2023

25. Anon (2008): Draft Conservation Area Statement - Industrial Heritage Conservation Area: Volume 1, Stroud District Council; p41

26. Baines, Edward (1859): On the Woollen Manufacture of England in Quarterly Journal of the Statistical Society Vol. 22, No. 1 (March 1859); p4

27. Ibid; p27

28. Baggs, Jurica & Sheils (1976): p181-182

29. Unidentified Adelaide Newspaper, c.January 1904; shared on ancestry.com by one of George Smith's descendents

30. Bristol Times, 31 March 1849

31. Cheltenham Chronicle, 5 April 1849

32. Definitions of Hearing Impairmnets, British Deaf Association

33. History of Deaf Education, Centre for Deaf Studies, University of Bristol; year and author unknown due to Bristol University website being terribly designed.

34. Topi, Skender; Santacroce, Luigi; Bottalico, Lucrezia; Ballini, Andrea; Inchingolo, Alessio Danilo; Dipalma, Gianna; Chaitos, Ioannis Alexndros; & Inchingolo, Francesco (2020) Gastric Cancer in History: A Perspective Interdisciplinary Study, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; p6

35. The Washerwoman's Genes, accessed 13 Jun 2023

36. Winters, Riley (2016): The Fallen Women: Were Victorian Prostitutes Really Fallen?, Ancient Origins, accessed 13 Jun 2023

37. Mainwaring-Parr, Lucy (2021): Victorian Sex Workers, John's Chronicle, accessed 13 Jun 2023

38. The Clinical History of 'Moron,' 'Idiot,' and 'Imbecile', Merriam Webster; accessed 13 Jun 2023

39. Ray-Barruel, Gillian (2012): The Legacy of Special Education in Victorian England, University of Queensland

40. Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857, General Register Office

41. Regulating Grief: the Rules of Mourning and their decay in the Victorian and Edwardian Period, Happily Ever Taffeta, 2020; accessed 13 Jun 2023

42. Bailey, Ruth (2003): My Ancestor Was a Bastard, Society of Genealogists; p9

43. Stroud Journal, 15 May 1869

44. Spreadsheet - Stroudwater Emigration to S. Australia, Radical Stroud; accessed 14 Jun 2023

45. Records relating to official assisted immigration - Crown Lands and Immigration Office - Official assisted passage passenger lists, 1845-1886., Series GRG35/48/1, State Records of South Australia, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

46. Elementary Education Act, United Kingdom government, 1870

47. Stroud Journal, 21 September 1872

48. Burnett, John (1974): The Annals of Labour: Autobiographies of British Working Class People, 1820-1920, Indiana University Press; excerpted at The Victorian Web, accessed 14 Jun 2023

49. Punch, Jan-Jun 1850; reproduced at https://www.victorianlondon.org/professions/charwomen.htm, accessed 14 Jun 2023

50. Thomson, David (2008); Workhouse to Nursing Home: Residential Care of Elderly People in England since 1840, published in Ageing and Society, Vol.3 Issue 1, Cambridge University Press; p49

51. Stroud News, 27 December 1907

52. Thurley, Djuna (2008): Old Age Pensions Act 1908, House of Commons Library

53. Gloucester Citizen, 22 February 1907

54. Stroud News, 12 July 1907

55. Gloucester Citizen, 4 February 1907

56. Webb, Sidney & Beatrice (1910); English Poor Law Policy, Longmans, Green & Co.; p24

57. Annola, Johanna (2020) Workhouse Nurses in England and Finland, 1855-1914, published in European Journal for Nursing History and Ethics, Issue 2/2020; p16-17

58. Llovet, Josep M.; Kelly, Robin Kate; Villanueva, Augusto; Singal, Amit G.; Pikarsky, Eli; Roayaie, Sasan; Lencioni, Riccardo; Koike, Kazuhiko; Zucman-Rossi, Jessica; & Finn, Richard S. (2021): Hepatocellular Carcinoma, published in Nature Reviews Disease Primers 7, article 6

59. Osborne, Harvey (2018): John Bright's Poacher: Poaching, Politics and the Illicit Trade in Live Game in Early Victorian England; Agricultural History Review, 66 (2), p215-217

60. Nailsworth, St George's, burial registers 1905-1962, Gloucestershire Archives

61. workhouses.org, accessed 15 Jul 2023

62. The history behind your birth certificate, Anglia Research; accessed 24 Jul 2023

To go back to the Philpotts-Shipton tree, click here