James Kenworthy 1787-1845

Childhood 1787-1799

James Kenworthy was born during or perhaps shortly before January 1787, in the hamlet of Sandbed, near Delph in the parish of Saddleworth, Yorkshire, and was baptised at St Thomas Friarmere on 20 January 1787[1]. He was the fourth child of John Kenworthy and Mary Broadbent, who like many Saddleworth inhabitants were textile workers in the wool or cotton trade[2]. His elder siblings were Mary ("Mally") (b.1780), Elizabeth ("Betty") (b.1783) and John (b.1784), and his younger siblings were Robert (b.1788), Ann (b.1790), Jeremiah ("Jerry") (b.1792) and Sarah ("Sally") (b.1794).

Few details can be gleaned about James's early life. His childhood home was possibly the listed building now known as Sandbed House[Note 1], built in around 1770, a three-storey stone building that would have housed several families[3]. Baptism records show that other families inhabiting Sandbed around the same time included shoemaker James Heley, his wife Patience Dawson, and their sons John and James born 1787 and 1788; clothier John Scholefield, his wife Betty Buckley and their children Henry and Sarah born 1789 and 1791; and clothier James Scholefield, Alice Whitfield and their several children born between 1785 and 1794. It does not appear that any of these were closely related to our Kenworthys, although the two Scholefield men may have been cousins of James's father, whose mother's maiden name was Scholefield. Despite being surrounded by fields, it would have been a busy, noisy place to live. Textile production was still predominantly a cottage industry, so it is likely that several spinning wheels and handlooms would have been whirring and clacking away from dawn til dusk[4].

This was a period of great change for Saddleworth. As the industrial revolution gathered steam, large and intensive cotton mills were beginning to spring up, providing tough competition for the smaller independent textile workers[5][6]. To the west, the once modestly-sized town of Manchester was expanding into a sprawling metropolis of slums and smoking chimneys, a progression that would have been clearly visible from the overlooking hillsides of Saddleworth[7]. In the mid-1790s work began on an ambitious canal project connecting Huddersfield with the town of Ashton by way of Saddleworth. This would eventually involve the carving of a huge tunnel into the moors, a little over a mile to the east of where James grew up[8]. This remote and sparsley-inhabited corner of Yorkshire was gradually being opened up to the outside world.

James probably attended a local free school, possibly a Dame School of which there were many in Saddleworth[9]. These would be run by a woman in her own home, and could provide basic literacy and numeracy for working-class children, although some were more a form of daycare or even unpaid domestic service (by the children)[10]. There was in fact a Methodist Sunday School established within Sandbed in 1786[60], although since James and most of his siblings appear to have been loyal Anglicans, it seems unlikely that they were sent there. We know from later records that James, John and Ann were able to read and write as adults, although Robert, Jeremiah and Sally do not appear to have been confidently literate (later details of Mally and Betty's lives are uncertain). James probably had at least fairly good numeracy skills as his later career would have depended upon it, although his ability to keep track of the passing years was apparently not perfect, as he would later underestimate his own age by two years.[Note 2]

From Home to Holmrook 1800-1827

Eldest brother John was probably the first of the Kenworthy siblings to leave home. He would become a mechanic as an adult, so he was likely sent off to begin an apprenticeship in his early or mid-teens. This was probably a few miles to the south, in or near the parish of Mottram, Cheshire, as this is where he would marry in 1820 and spend the rest of his life. James's younger brother Robert also appears to have headed in this direction, as he married at Mottram in 1811, but he does not seem to have secured any apprenticeship and would work as a cotton spinner. Middle sister Ann married the brother of John's wife in 1822, and would settle some way to the north in Clitheroe. Eldest sister Mally appears to have married a local clothworker who was part of a Baptist congregation, although as her name is very common and there is a shortage of corroborating evidence I cannot be sure this is her. Youngest brother Jeremiah would become a plasterer in Manchester, so he too probably completed an apprenticeship. Youngest sister Sally is the only sibling known to have remained in the same area they were all born in. She married at Saddleworth in 1815 and in 1841 lived at Dale which is adjacent to Sandbed. There is copious evidence to suggest that the siblings remained in close contact as adults. The fates of their parents are not entirely certain. Inclosure records of 1810 reveal that a John Kenworthy was an occupier at "Sandbed Yate [or Gate]"[11]. Mary possibly died in 1819 at Linfitts near Delph. If this is her, she was reportedly a widow by this point, although no plausible death record can be found for John.

As for James, the first time he surfaces as an adult in surviving records is in the mid-1820s when he was working as the butler at Holmrook Hall in the parish of Irton, Cumberland, some seventy miles from the place he was born. Holmrook Hall was then the official residence of Major Skeffington Lutwidge (1779-1856), local magistrate, deputy-lieutenant of the Cumberland Militia and great-uncle of the author Lewis Carroll[12][13][14][15][Note 3]. It is not clear how James came to be in the Major's service. To be considered for such a position, he must have had some early experience in service or catering. He could have got his start at The Bell Inn in Delph, a large coaching house established in the 1790s[16], or perhaps as a junior servant in a local manor house. The fact that he ended up so far from Saddleworth suggests he may have been referred to Holmrook by an acquaintance or relative of the Major for whom he had previously worked.

Holmrook Hall (or Holm Rook as it was known at the time) was a relatively small manor house, but as its butler James would have been the most senior male servant, as well as head of the kitchen staff. The role could vary from one household to another, but with Holmrook being a smaller residence it is likely James's duties were quite broad, and would have included things like ensuring the furnishings and kitchen equipment were in good condition and properly accounted for, keeping stock of the wine cellar, receiving guests at the door, and generally overseeing the activities of other servants. It was broadly more of a managerial than a hands-on role.[17][18] However, if there was no valet, he would also have carried out personal assistance tasks such as arranging his master's clothes. The typical butler's attire was a rather ornate livery uniform, complete with powdered wig, in a style that was a holdover from the fashions of the previous century. His earnings would have been in the region of £50 a year, equivalent to that of a skilled tradesperson.[19]

We have no date for when James first became butler at Holmrook, nor any indication whether he held a more junior role (such as footman) at the Hall beforehand. A predecessor, a Mr Robert Holderness, died in 1823[20] and was last known to have been working in 1817[21]. James was definitely in post in 1825, in which year the county newspaper Cumberland Pacquet erroneously reported him as having died "in the prime of life", after a four-hour illness. The article noted that "the deceased was universally respected"[22] . The source of the error is not revealed, but in the following week's paper it was firmly refuted by an anonymous letter-writer, who proclaimed "on the most unquestionable veracity, that [Mr James Kenworthy] is alive and well", so we can assume that the short illness was also a misattribution. The writer attaches no blame to the newspaper, assuming that they had been misinformed, but opines that "he who reports the death of another, whom he knows to be living, is totally destitute of the finer feelings of human nature"[23]. I have a sneaking suspicion that the letter-writer was none other than James himself.

An 1825 book called The Complete Servant, addressed to prospective employers, offers the following advice on the relationship between butlers and their masters:

Let there always be a strict friendship between you and the butler, for it is both your interests to be united: the butler often wants a comfortable tit-bit, and you much oftener a cool cup of good liquor. However, be cautious of him, for he is sometimes an inconstant lover; because he hath great advantage to allure the maids with a glass of sack, or white-wine and sugar.[24]

Husband, Father and Odd Fellow 1828-1839

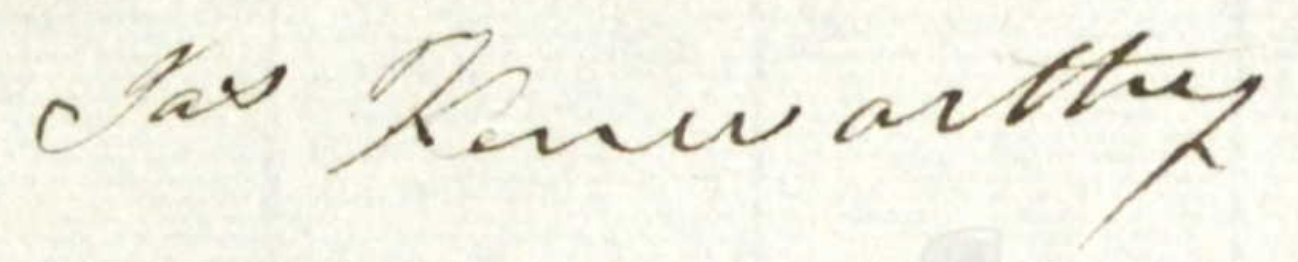

On 26 May 1828 James married Agnes Williams, who was almost certainly another member of the household staff at Holmrook, at the parish church in Irton[25]. Twenty-nine years old to James's forty-one, she was a butcher's daughter from the nearby town of Egremont a few miles to the north, but was also resident at Holmrook Hall at the time of the wedding. Unfortunately the actual marriage record appears not to have survived, so we do not know who the official witnesses were. A marriage license however does exist, and it provides us with our only known example of James's signature. It is rather confusing that they chose to obtain a license at all; since they were both resident in the parish, they should only have needed to wait three weeks for the banns to be called. A common marriage license then typically cost between two and three pounds[62], roughly equivalent to between £135 and £200 as of 2017[63]. It may be that they did not want the publicity of banns, or perhaps they needed to marry especially quickly for some reason. They may simply even have chosen to pay for the license as a symbol of prestige. The license was issued on 19 May, one week before the wedding.[26]

It was quite common for butlers, upon marrying and leaving service, to become the proprieter of a public house[27] since they had the experience in the preparation food and drink and the management of staff. James was no exception, and shortly after his marriage took up the running of the King's Arms Inn in Agnes's home town of Egremont. There had probably been some amount of pay set aside, and they may have deliberately waited for the King's Arms to become available, as it was one of the larger such places for some miles around.

James was in fact never the owner of the King's Arms, which was held by an unknown landlord. The first evidence we have of him being there is in November 1828, when it hosted the auction of a different property, and the King's Arms is referred to as "Mr Kenworthy's"[28]. Owing to its size and local prominence, the King's Arms was something of a community hub, and events such as auctions and society dinners would quite frequently be held there. The property was sold the following month, this time to a Mr Benn of Monkwray. The sale notice describes it as a coach house "in good Repair" with adjoining stabling, plus "an excellent Garden and a small Field"[29].

James and Agnes's first child was born in April 1829, and named George Williams Kenworthy. This followed a tradition in some families of giving a child, often the eldest son, the mother's maiden name as a middle name. The name George was also from Agnes's side, being the name of her father. A second child, named John, was born in November 1830, followed by James Wright Kenworthy in 1832. This middle name Wright, while appearing to be derived from another surname, was in fact an occasional given name in parts of northwest England. Although it is not known to have been appeared in previous generations of the Kenworthy or Broadbent families, James's brother John's first child was named Wright in 1820, and the name would also be given to their sister Sally's seventh child in 1835. James's fourth child Jane was born in November 1833. Egremont's baptism records for this period are now lost[30], but the births of James and Agnes's children are attested from later documents.[31]

In September 1832 we have our earliest account of one of the many festive events hosted by James and Agnes at the King's Arms, in this case a dinner for attendees of the Egremont Crab Fair, described in the Cumberland Pacquet as "a substantial repast, prepared by Mr K. in the very first style". In addition to the catering, James also acted as one of two stewards for a series of sporting events held at the fair, which included shooting, wrestling and a sack race. Again the Pacquet is generous with its praise, stating that James and his co-steward Mr Tolson were "indefatigable in their exertions to give all possible care to the amusements; and never, perhaps, were stewards more successful"[32].

James appeared in the newspaper for less pleasant reasons in April 1834. In November the previous year, he had been part of a group of local men who raided the home of a Mr and Mrs Christian, and appeared along with his co-conspirators at the Cumberland Quarter Sessions court in Carlisle on charges of riot and assault. The Christians had owed rent to their landlord Dr Lawson, apparently a friend of James, and Lawson wanted to retake possession. According to the victims' testimony, Lawson, James and four other men broke into the house with crowbars, terrifying Mr Christian and his daughter. Later, Mr Christian's wife and sister-in-law arrived at the house, whereupon some kind of altercation occurred. According to Mrs Christian's testimony: "Kenworthy grabbed my sister and took her by the bonnet strings. I could see her getting black in the face". Lawson allegedly shouted "Kill the bitch - kill her". A third member of the gang was then said to have struck Mrs Christian's sister in the head with a crowbar, causing her to bleed profusely. In their defence Lawson and his gang claimed the woman had only been pushed, and her wound had been received in falling and striking her head against a broken pot. They also claimed the other allegations of violence and threatening language were fabricated. James's old master Major Lutwidge acted as character witness, and the court concluded that "the account by the prosecution was very much exaggerated, that Mr Lawson and the others were unlikely men to use the expressions or perform the acts attributed to them". After three hours' deliberation by the jury, the man who had struck (or pushed) Mrs Christian's sister was fined 20 shillings, and all other charges were dropped[33].

In October 1834, the King's Arms was itself turned into a makeshift courthouse, as it became the venue for the Revising Barristers' Court for the Registration of Voters. As the right to vote was then granted based on the value of property one was holding or leasing, and since the Reform Act of 1832 had expanded that right to those on land valued at £10 or more (still quite a considerable sum well out of reach for most working people), these revising courts were established to settle any marginal claims for enfranchisement[34]. The court ran over two days and had numerous attendees. Among the several dozen cases heard was that of James himself. No specific details are given, only that his registration was initially objected by one of the barristers, a Mr Perry, but that this objection was withdrawn[35]. As it turned out, James's right to vote was neither here nor there, since Tory candidate Matthias Attwood was elected unopposed at every subsequent election in James's lifetime[61].

Two more children were born to James and Agnes in the following years – Agnes in January 1835, and the youngest, Robert, in June 1836. The name Robert was probably chosen in honour of James's younger brother, who was the closest in age to James of all his siblings. All the children survived into adulthood. It is possible that there was one more child born in the late 1830s who died in infancy, but if so no mention of them has survived.

James became a member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows[36], and in January 1838 was probably a founding member of his local branch, the Earl of Egremont Lodge. The Oddfellows were a fraternal organisation who, like the Freemasons, were organised into lodges and referred to their members as "brothers". They also acted as a friendly society, a form of insurance whereby members would pay into a mutual fund, which would then be used to support any member of the group who became unemployed or disabled. A breakaway group from the original Grand United Lodge of Odd Fellows formed in Manchester, the Independent Order was becoming quite popular and respectable in the north of England, despite organisations of its kind being technically illegal until 1851[37]. Another prominent member was Dr Lawson, with whom James had appeared in court four years earlier. Naturally, the King's Arms would host the Lodge's social events[38].

By now the inn had quite a reputation for lavish feasts and impeccable hospitality. In 1834 The King's Arms was chosen as the venue for the West Cumberland Agricultural Society's Autumn Show, the first time the event had been held in Egremont. To accommodate all the guests, James organised the raising of a tent on the field backing onto the inn, "of sufficient width to allow two sets of tables, plates being laid for 310: The place was lighted up before the dinner commenced by a large number of chandeliers, and the tables were elegantly decorated with flowers and ever-greens: the rough wooden pillars which supported the roof were entirely covered with the foliage of the garden [...] In the centre was a dais, upon which the Chairman's seat was fixed"[39]. This effort clearly left a good impression, as the Society chose to hold its Autumn Show there again the following year[40].

On New Year's Day 1839 the Earl of Egremont Lodge's anniversary dinner was attended by so many people that there wasn't enough room and they had to eat in shifts. The write-up of this event in the Pacquet paints a vivid picture of the Oddfellows' extravagance and standing in the community. The neighbouring Loyal Solway Lodge of Whitehaven marched to Egremont in a procession of flags and banners with a band at their head, a spectacle said to have cost fifty guineas. They then attended a special service at Egremont rectory, where the reverend quoted Ephesians 25: "every man speak truth with his neighbour; for we are members one of another". After the dinner at the King's Arms, the Lodge's chairman (Dr Lawson) toasted the health of the queen, the army and the navy as well as various individuals present. The guests from Whitehaven did not depart until seven in the morning, and the members of the Egremont Lodge remained talking amongst themselves for a further three hours[38].

On 21 February 1839, less than two months after these celebrations, James's wife Agnes was found dead in her bed, probably discovered by James himself. A coroner's inquest was held the next day, which determined that there was no mark upon her and that she had died "by the visitation of God", which was then the standard way of saying that the death was natural and not caused by accident or foul play. No further details are given, but its suddenness suggests something like heart failure or an aneurysm[41][42].

Final Years

Life carried on at the inn, but there was an understandable halt to festive events while the family were in mourning. When those events returned they were perhaps somewhat more low-key, although no less well-received. In December 1840 there was a special supper in honour of the Earl of Egremont Lodge's retiring treasurer, which was described in the Cumberland Pacquet as being "composed of every variety of which the festive season admitted, and was served up in a manner highly creditable to the taste and judgment of the worthy host"[43].

On the 1841 census we find James at the King's Arms with his six children. The household has three servants - Thomas Muncaster aged 50-54, Elinor Roberts, aged 60-64. and Sarah White aged 30-34. Servant roles were almost always segregated by gender, so Thomas Muncaster was perhaps an ostler, responsible for the stables and looking after guests' horses[44]. Of the two women, one was probably a kitchen servant and the other could have been employed to look after the younger children. Elinor Roberts may have been a relative of Agnes's mother, whose maiden name was Roberts.

A handful of events are documented as taking place at the inn during 1841 and 1842, including the drawing of the dogs for a hare-coursing meet[45], another Oddfellows anniversary[46], and a dinner for the Egremont Agricultural Society[47]. It was also enough of a community meeting point that Egremont's only copy of the Notice of the Rent Charge levied by the Tithe Commission was displayed there in 1841[48]. After this, the only reference we have to the inn being used as a venue under James's tenure is an auction in 1844. It may be that as James aged and without Agnes at his side, he was becoming less able to oversee the more spectacular affairs the King's Arms had once played host to. A later source reveals that James had been brewing his own beers at the inn[49], so he may have begun focusing more on this, although I can find no references to it from during his lifetime.

In October 1843, James was out for a ride in a gig, when shortly before returning home the horse became distressed and caused the vehicle to overturn. James suffered a fracture to his leg below the knee. He received medical attention, perhaps from his friend Dr Lawson, and as the Pacquet would report the following week "the injured limb is fast recovering its wonted strength, so that there is no fear but the worthy host of the Royal Arms will soon be well again"[50].

James's eldest children were now entering their teens. George may have been the first to leave home. He would become a tallow chandler, so at some point he probably went off to begin an apprenticeship, possibly in Whitehaven where he would later live. More certain are the activities of second child John, who was drawn to a nautical career. In the autumn of 1844 he signed up as an apprentice with the firm of T&J Brocklebank, who were based at the nearby port in Whitehaven. His first voyage was a round trip of five to six months. Father and son probably did not see each other again.

James died 10 March 1845. The cause of death was given as "an affection [e.g. an illness] of the liver", which tells us very little. However, since there was no inquest we can assume it followed a period of poor health and was not sudden as Agnes's had been. The death was reported by Jane Ashbridge, who appears to have been a relative of James's neighbour, and had possibly acted as a nurse to James in his final hours. A brief account of his funeral in the Cumberland Pacquet notes that several brothers from the Order of Odd Fellows walked in procession before his coffin[36].

Legacy

There was no will. A sale of furniture and other possessions three weeks after James's death implies he had run up some debts towards the end of his life. The full list of items for sale was recorded in the Pacquet, and gives us an impression of the scale and sophistication of operations at the King's Arms. It reads:

One large Mahogany Dining Table, Three Walnut Dining Tables, Half a Dozen Mahogany Card Tables, Two Dozen Mahogany Chairs, Hair Bottoms [probably refers to chairs with a horse-hair seat], Elbow Chairs to Match, One large Mahogany Sofa, Two small Sofas, Two Dozen Bed Room Chairs, Two Dozen Oak Chairs, and a number of Kitchen Chairs; One Mahogany Desk, Four Mahogany Dressing Chests, Chest-upon-Chest, Mahogany Wash Stands, Dressing Tables, a Clock and Case, One Night Commode, Six Feather Beds, Mahogany Bedsteads, with Moreen [a decorative woollen hanging] and other Hangings, Feather Bolsters and Pillows, Quilts, Blankets, Sheet, and Table Linen; Hearth Rugs, Brass Rods, Oil Cloths, Mattresses, Fire Screens, Brass and other Fenders, Candlesticks, a Lobby Lamp, Tea Trays, China, Glass, and Earthenware; Paintings and Chimney Ornaments, Two large Pier Glasses [mirrors], and several Dressing Glasses, Three good Fowling Pieces [guns used for killing game birds and other small animals], Two Mahogany Butler's Trays, Warming Pan, Brass Pans, an excellent Set of Dinner Service, Four Dozen Knives and Forks, Two large Kitchen Tables, Two Oak Clothes Chests, Two Cribs, Mattresses, Beds, and Pillows. […] Brewing Utensils, consisting of Half Barrels, Quarter Casks, and all the Apparatus belonging to the Brewing Business.

One Horse, Suitable for Saddle or Harness, One Cart, One Gig, Tub, and Harness. A Quantity of Hay and Potatoes, Beams, Scales and Weights; an excellent Set of Cart Gear, Saddles and Bridles, and the whole of the Stable and Garden Implements.

The sale notice requests that James's creditors forward their accounts immediately to a specific solicitor's firm in Whitehaven.[49]

The King's Arms was advertised for let[51], and the subsequent tenant was named John Benn, suggesting he was a relative of the then-current owner. Benn put a notice in the Pacquet for the re-opening in October 1845, proclaiming in a perhaps-inadvertent slight towards his predecessor that the inn had undergone a "thorough and expensive repair" and was now "more commodious and comfortable"[52]. It continued to be a venue for auctions, but there are no more accounts of it hosting lavish dinners or society gatherings in the years following James's death. The Earl of Egremont Lodge was now holding its events at the Red Lion Inn, run by a "Brother" Sewell[53]. Benn's tenure at the King's Arms did not last long, as the property was advertised to let again in September 1847 for immediate possession[54]. A new tenant was apparently not forthcoming, as it was advertised for let once again in February 1848, this time mentioning that Mr Benn was deceased[55]. The inn is still in operation as of 2023, and has retained the name King's Arms.

The now-orphaned younger children were taken into the guardianship of Agnes's brother James Williams, a farmer also living in Egremont, and his wife Sarah[56], who had no children of their own. The youngest of the Kenworthy siblings, Robert, was still with the Williamses until at least 1851. By this point Agnes was a servant for another of her maternal uncles, George Williams. She never married, and after working in service through her 20s and 30s would live as a guest with various family members. Jane was staying with James's brother John in Mottram. She would marry a shipping clerk, and settle in Liverpool. Third child James Wright was in a carpentery apprenticeship with yet another uncle, Joseph Williams, but would later study for the priesthood at St Bees college and serve as curate at a number of parishes around the country. John would remain in the merchant navy, eventually becoming a clipper ship captain, a career which youngest brother Robert would follow him into. Eldest child George was the only sibling who would remain close to Egremont, running his chandlery business in the coastal town of Whitehaven.

There is a small and oblique reference to James in a poem written by his son John in 1858. The poem, dedicated to an especially kind-hearted First Mate who restored John's faith in humanity, opens with:

A father's hand, a mother's kiss,

My early ties were gone.

Tho – oh, I cannot speak of this -

I stood, myself, alone.[57]

The "father's hand" contrasted with the "mother's kiss", is probably a reference to physical beatings, as opposed to the tender parenting of Agnes. Punitive violence by fathers towards their children was sadly regarded as quite normal in this period[58]. John's choice of words regarding his parents foreshadows the poem's principle theme of seeking out kindness in a world full of cruelty, and suggests he may have been somewhat terrorised by his father, which perhaps fuelled his decision to trade the family home for a life on the ocean at such a young age.

None of James's children are known to have had any association with the Earl of Egremont Lodge or other branches of the Odd Fellows, although George became a member of a much more prominent fraternal organisation, the Freemasons. The Egremont Lodge kept going for several decades, but does not seem to have survived far beyond the Victorian era. The latest reference I can find to its being active is from July 1913, when an article in the West Cumberland Times reported the annual parade of the Lodge's Juvenile Branch, which was apparently looked forward to every year. In an echo of that First Anniversary parade in 1839, the young Odd Fellows convened in the parish church, where the preacher, presumably an old Oddfellow himself, told them:

"A man who is an Oddfellow need never fear that he is bearing life's burden alone. If trouble, need, sickness, or any other adversity overtakes him, each member can have the ready and sympathetic help of 1½ million brothers."[59]

With the outbreak of war a year later, presumably many of these "juvenile" Oddfellows went to fight in Europe, with some of them never to return[Note 4].

James's story is an example of how the upheaval of the industrial revolution and regency era could produce some startling changes in fortune. The coming of the mills to places like Saddleworth spelled disaster for many textile worker families, who after generations of carrying on their trades at home now found themselves labouring with little rest at huge and dangerous machines for meagre pay. Howeve, a lucky few (almost invariably men) who managed to get the right opportunities at the right time, were able to secure their place amid the upper-middle class. With little apparent regard for his humble origins, James seems to have embraced a life of rubbing shoulders with landowners, professionals and clergy. He gained not only the luxuries of comparative wealth, but also of reputation. When he and his friends broke into the home of a less well-off family, and James may or may not have attempted to strangle a woman with her own bonnet strings, it took only a good character testimony from his former employer to see all charges against him dropped. James Kenworthy left the world with debts, but for the most part his good social standing was inherited by his children, his sons ending up in very "establishment" careers, either in commerce or in James Wright's case, the Church of England. The history of the Kenworthy family from the mid-nineteenth to early-twentieth centuries was filled larger-than-life characters and fascinating, sometimes tragic, twists and turns. For better or worse, James played his part in setting that history in motion.

Notes

1. There are two buildings from this period that make up Sandbed today - Sandbed House and Sandbed Farmhouse. As the Kenworthys were not farmers, we can assume they did not live in the farmhouse. An 1810 record indicates that James's father John was an occupant at Sandbedyate or Sandbed Gate, which may be the then-name of Sandbed House, or a different building entirely which has since been demolished.

2. On his marriage license of 1828 James's age (which he presumably supplied himself) is given as 39, when he was in fact 41. On the 1841 census he is recorded as being 50, but on that census the ages of all adults were rounded down to the nearest 5, so the age given could have been accurate or once again underestimated by a few years. On his death certificate, written two days after he died, he is recorded as having been 56 when he was actually 58. James could (obviously) not have supplied this age himself, but it was probably his believed age based on what he told surviving friends and relatives while he was still alive. Curiously however, his death notice in the Carlisle Journal accurately states that he was 58. This notice was written twelve days after James's death, so perhaps by this point someone had been able to check the Friarmere baptism records, or maybe one of his siblings with a better head for dates had been able to provide the correct age. Note that James's actual date of birth is not known, but I have assumed it was either in January 1787 or late in 1786 based on his baptism date. In any case, he cannot have been as young as he stated on his marriage license.

3. The history of which member of the Lutwidge family held Holmrook at any given point is somewhat convoluted, and earlier in my research I incorrectly identified James's master as Major Charles Lutwidge (1768-1848), the older brother of Major Skeffington. In the late 18th century the hall was the residence of Henry Lutwidge (1724-1798), the father of both Majors, upon whose death the hall was inherited by Charles. Charles however chose to sell the hall to his uncle Admiral Skeffington Lutwidge (1736-1814). When the Admiral died he bequeathed the hall to his nephew Major Skeffington, who seems to have been its owner and occupant until at least 1844. My confusion mainly arose over the fact that the one reference to James's old master calls him only Major Lutwidge, with no first name, and the fact that Charles was at one point the hall's owner. However the various transfers of ownership are recorded (see references 12-15), and since Charles settled in Hull whereas Skeffington spent the best part of his retirement in Cumberland, any mention of a "Major Lutwidge" in Cumberland would almost certainly have reffered to Skeffington.

4. A list of names on the Egremont Cenotaph can be found here.

References

I have digital copies of all the various newspaper articles referenced below. If you wish to see the originals, please contact me. The bulletins of the Saddleworth Historical Society, which I reference several times, are all freely available to download here.

1. Anglican Parish Registers, Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives.

2. Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1930, Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives.

3. https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101162832-sandbed-house-saddleworth, accessed 28 May 2023

4. Saddleworth Records of Industrial and Economic History, Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 4 No. 2, Summer 1974

5. The Working Class of Saddleworth in the Industrial Revolution; Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 10 No 2, Summer 1980

6. The Depressions and Decline of the Domestic Woollen Industry in Saddleworth, Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 12 No 1, Spring 1982

7. Griffin, Emma: Manchester in the 19th Century, 2014; British Library

8. https://www.penninewaterways.co.uk/huddersfield/hnc2.htm, accessed 26 May 2023

9. Brierly, Morgan: A Chapter from a M.S. History of Saddleworth, publisher unknown (public domain), p15-16.

10. https://www.britannica.com/topic/dame-school, accessed 29 May 2023.

11. Manor Records: Saddleworth Inclosure Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 8 No.3 & Volume 9 No.2

12. https://www.cumbrianlives.org.uk/lives/skeffington-lutwidge.html, accessed 29 May 2023. Note that this article is mainly about the Major's more famous uncle, also named Skeffington, but it does indicate that upon the latter's death he bequeathed the hall to his nephew the Major.

13.Cumberland Pacquet, 15 October 1844; Skeffington Lutwidge advertising the hall as being to let, indicating that he was still its owner at this time, and had presumably been resident up to that point.

14. Anti-Gallican Monitor, 2 Feb 1823; Skeffington Lutwidge appointed Deputy Lieutenant of the County of Cumberland.

15. https://prestonhistory.com/subjects/lewis-carrolls-preston-family-connections/, accessed 29 May 2023; some general information on the various members of the Lutwidge family.

16. Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 7 No.4, Winter 1977

17. https://www.householdstaff.agency/blog/the-history-and-evolution-of-the-butler-profession, accessed 28 May 2023

18. http://www.rth.org.uk/regency-period/family-life/servants, accessed 28 May 2023

19. Adams, Samuel and Sarah (1825): The Complete Servant, Being a Practical Guide to the Peculiar Duties and Business of All Descriptions of Servants, Knight and Lacey, p7

20. Cumberland Pacquet 3 November 1823

21. Ibid 5 March 1839

22. Ibid 1 Feb 1825

23. Ibid, 8 Feb 1825

24. Adams, op cit, p231

25. Cumberland Pacquet 3 June 1828

26. Archdeaconry of Richmond, England, Church of England Marriage Bonds, 1611-1861, Lancashire Archives

27. Tracing Your Ancestors Who Worked in Pubs, Pub History Society, 2011

28. Cumberland Pacquet 18 Nov 1828

29. Ibid, 9 Dec 1828

30. http://www.archersoftware.co.uk/igi/fs-cul.htm#E, accessed 29 May 2023

31. Jenkins, Mollie (2001): A Very English Family, privately published, p287-350; [Mollie's book does in fact state the baptism dates for some of James and Agnes's children. I am not sure how she discovered these. Possibly they were recorded in surviving family bibles which she may have had access to].

32. Cumberland Pacquet, 25 Sep 1832

33. Ibid, 12 April 1834

34. https://www.historyhome.co.uk/peel/refact/refact.htm, accessed 29 May 2023

35. Cumberland Pacquet, 12 October 1834

36. Carlisle Journal, 22 Mar 1845

37. https://www.oddfellows.co.uk/about/history/, accessed 28 May 2023

38. Cumberland Pacquet, 8 Jan 1839

39. Ibid, 21 Oct 1834

40. Ibid, 7 Nov 1835

41. Carlisle Journal 2 Mar 1839

42. Item DLEC/6/4/157/9, Whitehaven Achive Centre

43. Cumberland Pacquet 29 Dec 1840

44. https://regencywriter-hking.blogspot.com/2020/03/the-regency-groom-ostler-postilion-and.html

45. Ibid, 5 Jan 1841

46. Ibid, 21 Dec 1841

47. Ibid, 16 Aug 1842

48. Ibid, 20 Apr 1841

49. Ibid, 1 Apr 1845

50. Ibid, 10 Oct 1843

51. Ibid, 25 Mar 1845

52. Ibid, 14 Oct 1845

53. Ibid, 24 Feb 1846

54. Ibid, 7 Sep 1847

55. Ibid, 1 Feb 1848

56. Jenkins, Mollie, op cit, p???

57. Ibid, p311; from an original manuscript privately held.

58. Frost, Ginger 'I am master here': Illegitimacy, Masculinity, and Violence in Victroian England, from L. Delap et al (eds), MacMillan 2009

59. West Cumberland Times, 5 July 1913

60. Saddleworth Historical Society Bulletin Volume 18 No 1, Spring 1988, p11

61. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitehaven_(UK_Parliament_constituency), accessed 26 May 2023

62. https://janeaustensworld.com/tag/marriage-licence-in-regency-england/, accessed 6 Jun 2023

63. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/, accessed 6 Jun 2023

For a full biography of James's son John, click here.

For brief biographies of James's other children, click here.

For brief biographies of James's siblings, click here.

For the Robinson-Kenworthy tree, click here.