Josiah Parkes 1787-1845

Early Life 1787-1807

Josiah Parkes was probably born in late 1787, in the village of Oldbury in the Black Country, the youngest of eleven children born to Isaac Parkes and Hannah Tunks. He was probably named after his maternal uncle Josiah Tunks, although some evidence points towards a Josiah on his father's side too. His older siblings were John (b.1765), William (b.1768), Isaac (b.1770), Mary (b.1772), Hannah (b.1775), Nanny (b.1777), Richard (b.1780), Samuel (b.1782), Sarah (b.1785), and Betty (b.1786). Of these, William, Isaac, Mary, Richard and Samuel are known to have been alive at the time of Josiah's birth, John and Sarah are very likely to have been alive, while Betty had died several weeks prior to Josiah's birth. The fates of Hannah and Nanny are uncertain.

Josiah was baptised at Oldbury chapel, on 9 December 1787[1]. Oldbury is situated about halfway between Wolverhampton and Birmingham, at the heart of a region that was being rapidly transformed by the industrial revolution. However Oldbury itself was still a small rural village, and would remain so until the 1810s[2]. Nevertheless its position between ample coalfields to the northwest and the industrial hub of Birmingham to the southwest was quite apparent. A writer in the 1780s tells of a continuous procession of coal wagons passing through "to the great destruction of the road and the annoyance of travellers"[3]. The Birmingham Canal, completed in 1772, also passed through the village[4]. By 1798, it would be the busiest canal in the country[5].

It is not known how far back the Parkes family's association with the coal trade goes, but it would come to shape the lives of Josiah and his siblings. Second eldest William was in business as a coal dealer, perhaps as early as 1790[6]. A 1795 register of canal boat owners reveals that William owned three boats, none of which were named but were simply designated Boats No.1, 2 and 3, and each of which was "usually navigated" between Tipton and Oxford. The slightly larger Boat No.1 was steered by William himself, while boats 2 and 3 were steered by middle brothers Isaac and Richard. Each boat also had a driver (whose job it would have been to guide the horse along the towpath), which in each case was noted simply as "a boy"[7]. Since this was clearly a family business, it seems very likely to me that Josiah (then aged seven or eight) was one of these boys. Samuel, aged around thirteen, may have been another. With Richard being only fifteen, it seems that the boys did not need to be very old to graduate to the more senior position of steerer.

Canal journeys between Tipton and Oxford would last several days[8]. Although most barges had cabins by this period, it was forbidden to sleep overnight on boats at many wharves, so crew members would instead stay at one of the many canal-side inns dotted along the route[9]. Public opinion of boatmen (as the steerers were commonly known) was seldom favourable, and they had a reputation for drunkenness, theft, and promiscuity. Drivers could be particularly cruel to their horses, with one account from 1783 describing the animals as "something like the skeleton of a horse", which the driver would "whip... from one end of the canal to the other"[10].

There was presumably not much time for any formal education in such a working childhood, and Josiah would apparently only be able to sign his name with an X. The same was also true of older brothers Isaac and Samuel, but not the other siblings. It is quite possible Josiah was parented as much, if not more, by his eldest siblings than he was his actual parents. A definite death date for Isaac Sr. cannot be found, but perhaps the most plausible is a burial from 1792, in which case Josiah would have lost his father at the age of just four. His mother died in April 1801, meaning that if his father did indeed die in 1792, Josiah was an orphan by the age of thirteen. Josiah may then have joined the household of one of his older siblings, with eldest brother John perhaps being the most likely candidate, although little is known about John's doings except that he and his family had lived in West Bromwich (which neighbours Oldbury, and was the birthplace of the siblings' mother). William was also in West Bromwich, and had recently married for the second time after being widowed. Mary meanwhile had married a butcher from Warwick. The three youngest siblings would all marry in Birmingham, suggesting that is where they spent their young adulthood.

Josiah would work as a boatman for at least part of his adulthood, so it would seem plausible that like his brother Richard he was deemed old enough for this position once he entered his mid-teens, working either for his brother or some other firm. William, now based in Aston near Birmingham and described simply as a carrier and dealer, became bankrupt in late 1803[11]. He would eventually rebuild his business, but for now it seemed the family's fortunes were at a low ebb.

Marriage and first business 1807-1819

Josiah married Martha Burton, daughter of a boatman from Smethwick, on 31 August 1807 at the church of St Martin in Birmingham. The couple were rather young, with Josiah being nineteen and Martha seventeen. In contrast, Josiah's elder siblings Richard, Samuel and Sarah were yet to marry, although the latter would marry a few months later. The official witnesses to Josiah and Martha's wedding were Charlotte Cooper and Richard Gibbs[12], who were presumably friends of the couple, and would themselves marry at the same church a year later[13].

Following their wedding, the couple moved to Josiah's home village of Oldbury. No one else in either of their immediate families is known to have lived in Oldbury at that time. Their first child was born in 1808, and named Edward, probably after a brother of Martha's.

It was in 1810 that Josiah began what appears to have been the first of many business ventures, when he bought a local village pub, called the George and Dragon[Note 1]. The sale notice describes it as being "situate in the populous and increasing village of Oldbury", and featuring:

"... five good upper rooms, a good Parlour, and a large Club Room, good Kitchen, large Pantry, two good Cellars, and Brewhouse complete; together with two good Gardens...[14]

At twenty-two, Josiah perhaps seems rather young for a pub landlord. However boatmen were rather well-paid despite their status, with some even able to afford multiple houses[15], and with his upbringing Josiah was no doubt familiar with such establishments. This too seems to have had connections to a wider family business, with a sale of William's property in 1820 revealing that he had been operating a brewhouse, and various other members of the family running pubs at one point or another.

Josiah and Martha's second child Thomas was born that same year, and named Thomas after Martha's father. No trace of Thomas can be found beyond his baptism, so he probably did not live into adulthood, although there is also no burial record for him in Oldbury. The couple's third child arrived in 1811 and was named Hannah, after Josiah's mother, and their fourth was born 1813 and named John. John was probably named after Josiah's eldest sibling, strengthening my suspicion that the latter became a surrogate father to Josiah after their actual father's passing. Whereas Edward and Thomas were baptised at Oldbury chapel, Hannah and John received no infant baptism and are known from later records. Since there is quite a long gap between John's birth and that of their next known child, it is quite possible that one or more children were born in the mid-1810s, also receiving no baptism but not surviving their childhood.

Josiah put the George and Dragon up for sale in December 1816, along with "Part of the Household Furniture and Fixtures, the Whole of the Brewing Utensils, and an excellent assortment of good Barrels". The premises were "in good Repair, well frequented, and in an improving Neighbourhood"[16]. The pub does not appear to exist today[Note 2].

The for-sale notice also states that Josiah had chosen to sell because he was "changing his residence". However the reason for this move is not entirely clear. The Black Country had seen growth, particularly in its iron industry during the Napoleonic Wars[18], which no doubt brought more trade to the local pubs. However in 1816 the country as a whole was facing severe economic hardship caused by a post-war downturn and the disasterous crop failures of what came to be dubbed the "year without a summer"[19]. Josiah may then have been forced to downsize, or perhaps preemtively chose a more reliable line of work.

The exact movements of the family over the next three years are not certain, but for at least some and perhaps all of that time Josiah was working as a boatman, probably along the route between the Black Country and London with eldest son Edward in the position of driver. However in contrast to the "man and boy" crews of the 1795 records, it was now becoming increasingly common for entire families to travel together, with all but the youngest children contributing to the work. One writer in 1819 observing boats entering the Blisworth tunnel (through which the Grand Junction Canal from Birmingham to London passes) stated that "the men, throwing off their upper garments and lighting up their lantern, gave the helm for steerage to the women"[20]. Having the family live on the boat certainly would have saved money in these difficult times, and it has in fact been theorised that the rise of "family boats" in this period was in response to a housing shortage during the recession[21]. Our only evidence of the family's whereabouts in the late 1810s comes in the summer of 1818 in Fenny Stratford, a small Buckinghamshire town that is arguably most notable for its canal wharf. It was here that the fifth child was baptised, and named Josiah like his father. It may be that this was where the family was now based when not on the canal, but it seems more likely to me that they were simply passing through at the time of the younger Josiah's birth.

Nevertheless, they would still have had to find seasonal accommodation (not to mention other forms of work) during the harsh winters of that era, when the canals would invariably freeze over[22]. They were perhaps not short of options however, as a tour up and down the canal route would have been practically a family reunion for Josiah. William, now an established lime and coal dealer, was the owner of Ashted Wharf in Birmingham. Mary and her husband and children lived at Saltisford in Warwick, which lies directly along the canal path. Isaac was running a canal-side pub and grocery store in Oldbury called the Navigation Inn. As with Josiah and the George & Dragon the only firm evidence we have of him being here is when he sold the premises, in his case in 1820, so it may be that both brothers had been running Oldbury pubs during the first half of the 1810s. Richard, after many years as a boatman, had recently become the lock keeper at the Ryders Green locks in West Bromwich, a position he would hold until his death in 1847. Samuel was also a boatman, and lived in Smethwick (between Oldbury and Birmingham) when not on the canal. Second-youngest sibling Sarah seems to disappear from records after she was widowed in 1809, but may have lived in Birmingham, her last known address.

From waterways to wheels 1820-1835

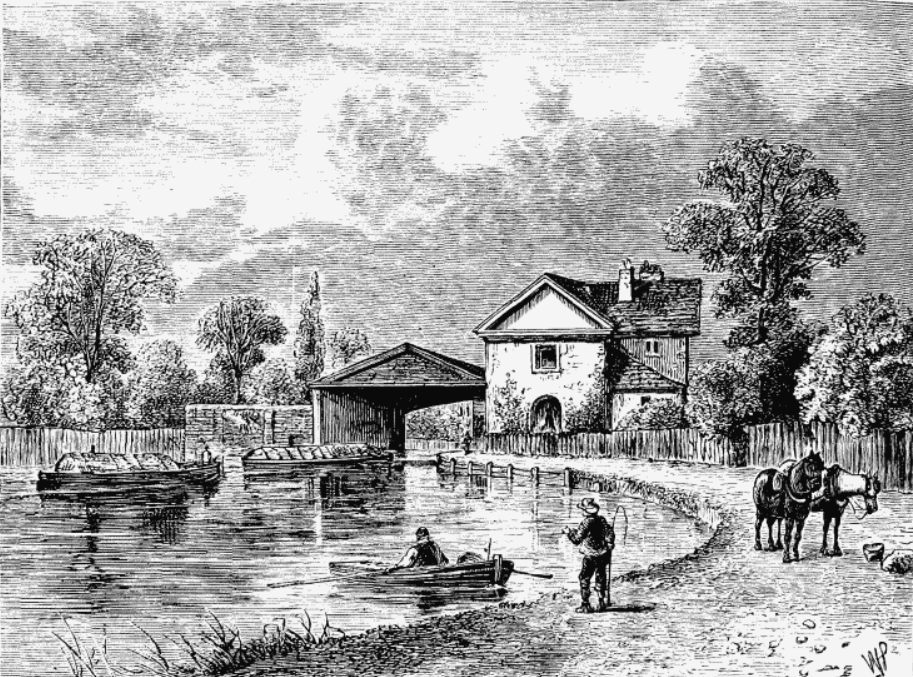

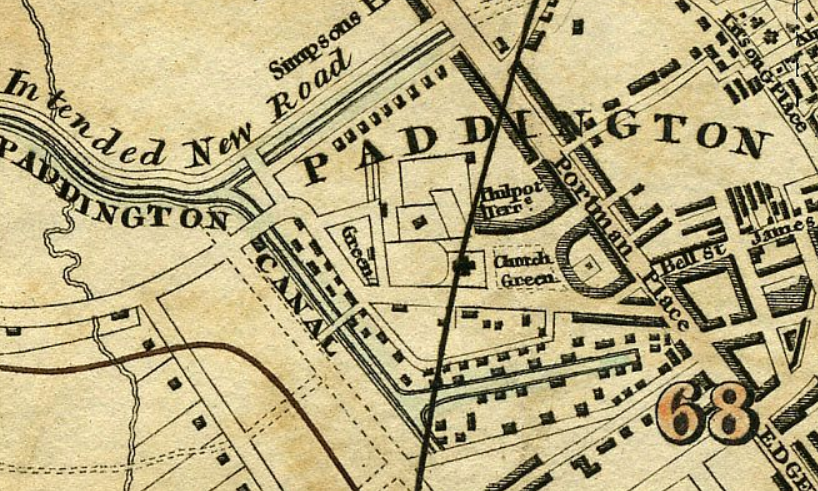

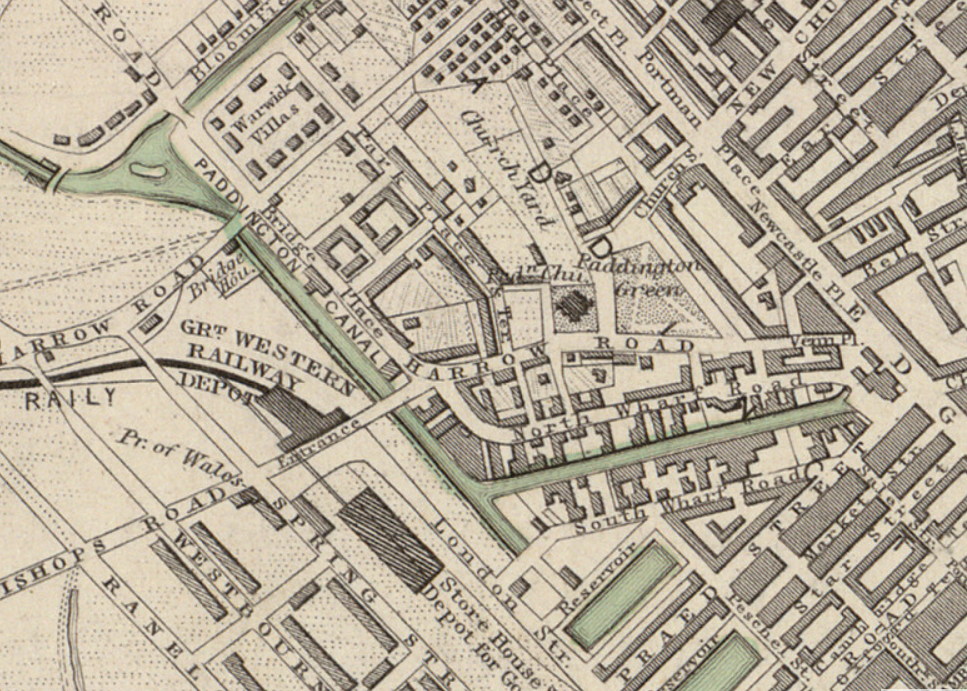

1820 was rather a turbulent year for Josiah's extended family. In April Isaac became bankrupt and was forced to sell off his pub and grocery store. This was apparently not enough to satisfy his creditors however, and the following month he was sent to a debtor's prison in London. William, perhaps having helped pay off Isaac's debts, also became bankrupt and in December sold his house, along with his wharf, a brewhouse and several limekilns. Josiah however seems to have fared rather better, since it is around this time that he and his family gave up travelling the canals and instead settled beside one, at Paddington basin terminal in London.

Josiah and Martha's sixth child was born at Paddington in 1820 and named Richard, presumably after Josiah's brother. He was followed in 1822 by Sarah. She may have been named after Josiah's sister, but Sarah was also the name of Martha's mother. Like their brother John before them, neither Richard or Sarah were baptised as infants.

Josiah's occupation in Paddington seems to have not been fixed, and it appears that like his brother William he engaged in multiple business ventures, perhaps focusing on whichever seemed most profitable at the time. In 1821 he described himself as a hay dealer of No.5 Wharf, Paddington, when he appeared at the Old Bailey courthouse as a victim of theft. One morning in April that year Martha had seen a carter named William Baxter taking a forty-pound truss of hay from their yard. She called for help from George Dixon, a boatman employed by the family, but they were not able to stop Baxter leaving with the hay. Baxter was caught and sentenced to a whipping and one month in jail[23].

When Josiah and Martha's eighth child, William, was born in around 1824, he became their first child since Josiah to be baptised in infancy. The baptism record gives Josiah's occupation as "carrier", which would normally be synonymous with carman, but from the available evidence I assume this refers to him owning a company which transported goods.

In 1827 the couple's ninth child was born and given the name Alexander Wilson Parkes. The name clearly does not come from either side of the family, and the form of it suggests he was named after a specific Alexander Wilson, although I have not been able to find anyone of that name who seems especially likely to have been well known by the Parkeses. A few months after his birth Alexander was taken for baptism, along with the children who had not been baptised as infants - Hannah, John, Richard and Sarah - and Josiah Jr. (whose baptism in Fenny Stratford they had presumably forgotten). Perhaps one of the children had had a recent brush with death, and Josiah and Martha had suddenly become concerned with the state of their offsprings' souls, or perhaps someone had let slip that the children were not baptised and some more devout neighbour had pressured the Parkeses into rectifying that. The register book only records the baptisms, not the story behind them.

Josiah's occupation was now listed as wharfinger, indicating that he owned and/or managed one of the wharfs. He also employed one or more carriers who delivered goods via horse and cart. That same year he appeared in court again, this time as the defendent. An "inspector of licenses"[24] named John Biers had him summoned to Worship Street Magistrate's Court for an offence under the Turnpike Roads Act, which stated that all carts must have the owner's full name clearly printed on them. Apparently Biers's witness had seen one of Josiah's carts with no name visible, and had asked the driver to point out the name, which the driver was unable to do. In his defence Josiah brought the cart to the courthouse, indicating that both his name and address were clearly printed on both the front and side of the cart. The witness contended that the cart had been dirty and thus the name had not been legible. The driver insisted that he cleaned the cart regularly, and that he had been unable to point out the owner's name himself because he could not read. The magistrate found in Josiah's favour and the case was dismissed[25].

In 1828 Josiah and Martha's son Josiah died at the age of ten, being the only one of their children known for certain to have died in childhood. The following year their tenth and final child was born, and named Martha like her mother. Unlike their parents (and Josiah's carter), the children do appear to have been given enough education to confidently write their names. The only children we do not have handwriting evidence for (besides those who died) are Edward and Alexander. Hannah was the first to marry, and in 1832 Josiah became a grandfather when her first child Mary Ann was born. The following year Josiah's son John married Isabella Cashmore, daughter of Josiah's sister Mary, proving that at least these two branches of the family had remained close. John and Isabella's first child was born in 1834, and named Josiah.

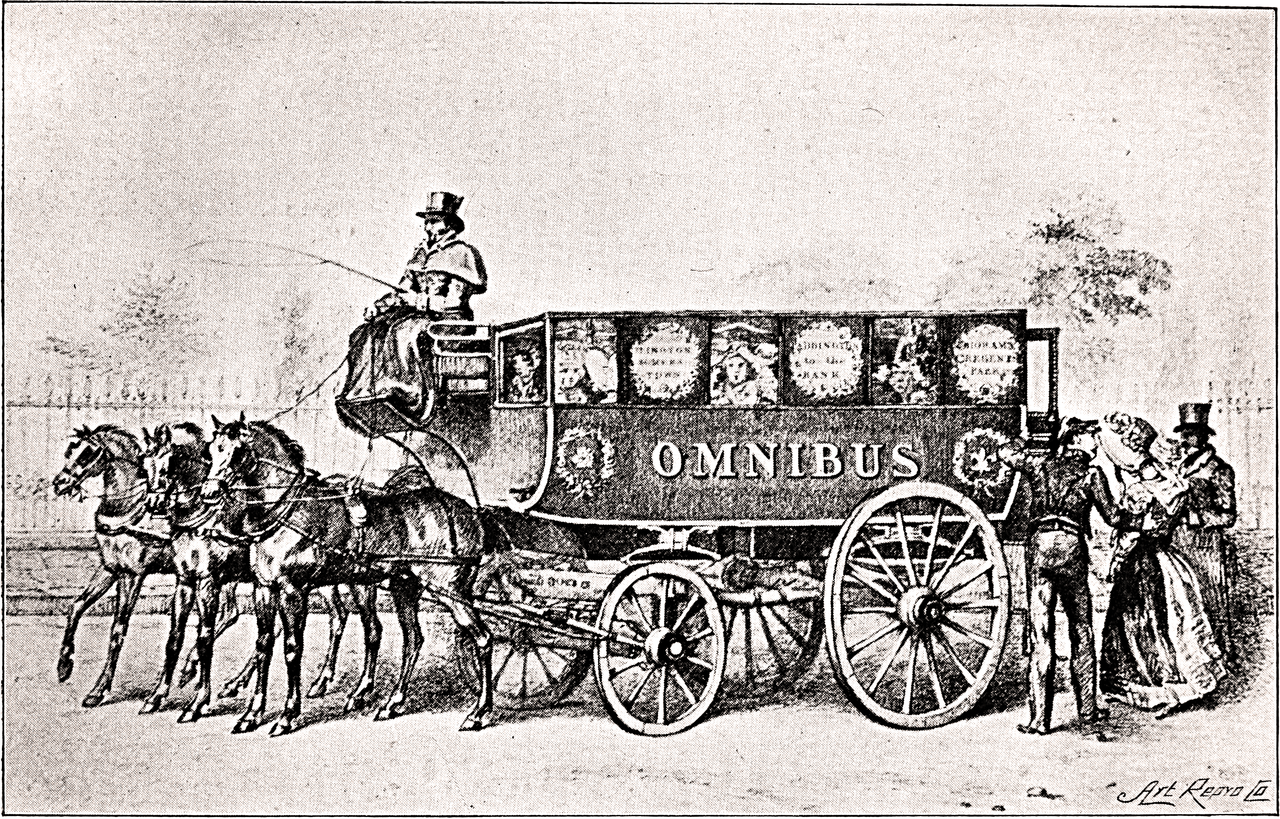

Josiah's success in business seems to have been at least partly down to his willingness to take on multiple ventures and to follow whichever industry was currently growing. As the supply from Black Country coal mines began to dwindle, bricks were becoming one of the regions principal exports[26], and sure enough we find Josiah listed in an 1835 trade as a brick and tile merchant[27] (as well as a wharfinger). However he was at this time also engaged in an even newer line of business, perhaps his most ambitious yet, and one that may well have been his undoing: The omnibus.

The Omnibus Debacle 1835

We do not have direct evidence of when Josiah became an omnibus proprieter. It cannot have been earlier than 1829, since that is when George Shillibeer began London's first omnibus service (which ran from Paddington to the Bank of England), but others were quick to follow his success and competition on the route soon became fierce[28]. If Josiah was running his omnibus firm by September 1831, then he probably attended a meeting of proprieters at the Wheatsheaf on Edgware Road, who formed an association to avoid direct competition by agreeing upon the number of buses and who got to run at what time[29]. Even if he was not a founding member of this association, he would certainly join it.

Like so many things the Parkeses did, Josiah's omnibus firm appears to have been a family business. Eldest surviving sons Edward and John were omnibus drivers. Third son Richard was an omnibus conductor, and it does not seem implausible that he began working in his early teens, considering his namesake uncle had been steering a canal boat around the same age. Josiah's son-in-law James Pilton (Hannah's husband) was also an omnibus proprieter and had been since at least 1831, but by 1835 he was described as just a driver, suggesting his own business may have folded and he was perhaps now working for Josiah. It is of course also possible that Josiah drove a bus himself. He had had three or four buses, a fairly typical number, with contemporary firms on the Paddington to Bank route having between two and six[30].

It was in June that year, that a horse dealer named Aaron Bray obtained a license to run two omnibuses from Paddington to Holborn, but did not join the aforementioned association of proprieters (or "the Paddington committee" as it was apparently now known). According to later court testimony, Josiah was the first member of the committee to approach Bray, turning up at the latter's yard in Holborn. They went to a local pub, where they drank brandy-and-water, and Josiah told Bray he was "a madman" if he did not buy times, and that the committee would "run [him] off the road, and ruin [him]". Bray however was not deterred. Some days later he was approached by three other proprieters - Robert Trevett, Wiliam Cowderoy and James Hill - one of whom grabbed him by the coat and "invited" him for a drink. Bray was once again pressured to join the committee, being told it cost members just 10 shillings a week, but that it would cost him twenty pounds if he were rash enough to oppose them. As the men got more drunk and Bray went to leave, Hill once again took hold of Bray and persuaded him to stay for another drink, boasting that the committe were "such bloody out-and-outers, they would beat anybody" and that they had ruined others before him. Bray, nevertheless, stood his ground[31].

That Josiah was the first to contact Bray suggests that he was by then quite well-established on the committee. It also perhaps gives up some insight into his character that, despite his threats, he appears to have taken up the "good cop" role in contrast to the more heavy-handed approach of Trevett, Cowderoy and Hill.

The threats of the other proprieters were not idle ones. Soon after these meetings Aaron Bray's son Robert, who drove buses for his father's company, found himself literally being run off the road. According to his testimony:

... the drivers of the other omnibuses tried to oppose us and to injure us, by pulling up against us — they would cross us and go before our buses, and their conductors would jump down, if passengers hailed us, to get them away from our buses...[32]

Another of Bray's drivers had the door panel of his bus being bashed in, and a would-be passenger described one of the committee buses being driven across his path as he was about to board Bray's bus. There was no mention of any specific action by Josiah or any of his drivers, except that his buses were among those involved in this harassment campaign.

The trial, which took place at the Old Bailey in August 1835, was lengthy with numerous witnesses for both sides. It emerged that Bray and his drivers had given as good as they got, and committed similar acts of intimidation against the committee members' buses and their passengers. No testimony from any of the defendents is recorded. Ultimately all but two of them were charged with conspiracy[33]. Two of the proprieters - Bolton and Trevett - were fined 100 pounds each. Josiah and several other proprieters were fined 50 pounds each, while the remaining proprieters and some individual drivers received smaller fines, with an order that they should be imprisoned in Newgate Gaol until the fines were paid. Bolton, apparently the Committee's treasurer, dispensed with the need for this by immediately writing a cheque for the full amount of 790 pounds[Note 3]. In his closing remarks the 44-year-old prosecuting barrister Charles Bompas proclaimed it was the longest trial of his career[34].

Final Years 1836-1845

Despite the apparent ease with which Bolton had paid the Paddington committee's fines, this financial blow - perhaps coupled with the negative publicity generated by the trial - seems to have hit the committee members badly. Of the twelve proprieters convicted in 1835, only five were still in business by 1838[36]. This is despite omnibus travel as a whole being a growing industry[51]. Some of Trevett's drivers were fined again in 1836 for obstructing the buses of another non-committee proprieter[52], whose drivers were also fined, but I can find no references to the committee after this. Josiah was amongst those no longer operating in 1838. He is listed in an 1840 trade directory under "scavengers and rubbish carters"[37], while other references refer to him only as a scavenger.

This was perhaps not as lowly a profession as it sounds. While it has sometimes been conflated in pop-history journalism with such unenviable jobs as bone-grubber and pure-finder[Note 4] in which one made money by selling what they collected, someone who ran a scavenging business (as Josiah surely did since he appeared in a directory of tradespeople) would be contracted by the parish to remove rubbish from the streets. Some such entrepreneurs could, apparently, become quite wealthy[38]. The parish would award a yearly contract to a single scavenging firm, but would directly employing "men for scraping and sweeping the roads". The contractor would have the responsibility of loading the refuse material onto its carts, which under the stipulations of Paddington parish it had to do within six hours of its being scraped and swept[39]. According to statistics gathered in the mid-1840s, there were between 4 and 6 people completing this task in the parish of Paddington, removing over 2000 cart-loads annually. After loading the scavengers would then cart the rubbish to a dumping ground known as a "shoot", which in the case of Paddington was a stretch of fields around Notting Hill and Kilburn[38]. It is not clear who Josiah employed to do the literal dirty work, or how much he did himself. His sons Edward and John were still omnibus drivers, presumably now under some other firm.

Regardless of how well he might have been paid in his scavenging business, Josiah was apparently in a large amount of debt. By August 1840 he was in a debtor's prison[40]. He was likely first sent to what was called a "sponging house", where his creditors' agents would have pressured him into settling, and if he was completely unable to pay he would have been imprisoned the following day. The exact prison he went to is not recorded. The debtors' prisons were profit-making institutions, where well-off prisoners (despite their debts) could pay for private rooms, beer and good food. Less fortunate inmates would endure the most squalid conditions with two or more to a cell.[41].

It seems Josiah was inside until at least November that year, when his case was heard at the Insolvent Debtor's Court on Portugal Street, a building that three years earlier Charles Dickens had described as "a temple dedicated to the Genius of Seediness"[42], with those on both sides of the bench having the lowest reputation. Josiah made two appearances that month, the first having been adjourned[43][44]. It is probable that his debts were finally resolved at this point, since there are no further insolvency records for him.

Josiah's entry on the 1841 census does not exist. The returns for the Paddington district are unfortunately lost[45]. Assuming he was not still in debtor's prison however, we can probably make a good guess as to what his household looked like. He lived on 14 North Wharf Road, which runs parallel to the canal terminal. Richard, William, Alexander and youngest child Martha still lived with their parents as per evidence from their subsequent appearance in records. Sarah, then aged nineteen, may also have lived at home, but could also have been working a service job elsewhere in the parish. Hannah had recently been widowed, and prior to her widowhood had lived in Kensington, but since she also cannot be found on the 1841 census it seems likely she had returned to Paddington with her three children. John and his family also lived on North Wharf Road. Eldest child Edward is the only one to appear on the census, since he and his common-law wife now lived in Stepney.

As for Josiah's own siblings, of those whose wherabouts are known: Mary still lived in Warwick with her husband. Despite the distance, there is likely to have been some contact between her family and Josiah's due to his son John being married to Mary's daughter Isabella. Isaac, whose financial dire straits two decades earlier seem to have been even worse than Josiah's, was now running a grocery store by the Tardebigg locks near Bromsgrove. Richard was still the lock keeper at Ryders Green. William had died in Birmingham in 1835. His daughter Mary Ann, now lived in London and may have had some interaction with Josiah and his family, since her son would later live on North Wharf Road and worked briefly as an omnibus conductor.

Following his stint in debtor's prison, Josiah's only known occupation was wharfinger, and he appears as such in trade directories during the early 1840s[46][47]. Josiah's wharf is here revealed to be Irongate Wharf[48][Note 5], not to be confused with the steamboat wharf on the Thames of the same name. The only reference I can find to the Paddington Irongate wharf during Josiah's tenure regards the bankrupcy of a hay dealer and omnibus proprieter by the name of Augustus Lines[49], who it seems may have taken over some of Josiah's previous businesses, with little more success. Rather confusingly, when Hannah remarried in 1842 the entry for father's occupation was left blank. The best reason I can think of for this is that Josiah was in poor health and did little or no actual work himself, but received an income from those paying to use the wharf. All records from after Josiah's death (including his death certificate itself) would describe him as a wharfinger, with the exception of William's third marriage in 1874, which stated his father was a scavenger. It is possible then that scavenging was Josiah's last "active" job.

It is perhaps not surprising that, as his other businesses collapsed, Josiah fell back on the canal as his source of income. It had after all been at the centre of almost everything he and his family turned their hands to, going right back to Josiah's childhood, and he had spent his entire life living on or next to it. Change was on the horizon, as the terminus of the Great Western Railway had been built in 1838 on Bishop's Bridge Road, a short way from the canal basin. However the railway's impact upon the canals was as yet minimal, and commercial traffic on the Grand Junction actually continued to increase up until the late 1840s[50].

In March 1844 Josiah may have appeared at the Old Bailey once again, this time as a juror[52]. However since the list of jurors gives only names, and there were at least two adults named Josiah Parkes living in London at that time, we cannot be certain that this was him.

Josiah died at his home on North Wharf Road at half past ten in the morning on 22 April 1845, at the age of fifty-seven. The stated cause was dropsy, an archaic term for edema. This painful condition, in which fluid builds up in the body's tissues, could have a number of causes, including heart failure, kidney disease or cirrhosis of the liver[53], but no particular details are given in Josiah's case. The death was reported by Richard, the eldest of the children still living at home.

At the time of his death, Josiah had eight living grandchildren, with roughly another thirty being born after he died. Three of his grandchildren - sons of John, Richard, and Martha - would be named Josiah after him. No one else in the family appears to have taken over the running of the wharf, and Josiah's sons would all have careers in land-based transport.

Notes

1. It is possible that he bought the George and Dragon somewhat later. The only evidence we have of him being there is from his sale notice in 1816, but 1810 was the most recent prior sale of the property that I was able to find.

2. Occasional references to a pub named the George and Dragon in Oldbury appear in newspapers up until the 1960s, and a 1968 photo of such a pub exists in the Black Country History archive. However the building in this photo clearly does not date back to the 1810s (I would guess early 20th century), so either the pub was rebuilt, or the original closed down and an unrelated pub of the same name was later opened. Neither does it appear that Josiah's George and Dragon still exists under a different name, as there are no extant pubs in Oldbury of that age[17].

3. To give an idea of the scale of these sums, Josiah's fine of 50 pounds would have been around 250 days pay for a skilled tradesperson. The combined fines of 790 pounds for all defendents were equivalent to just over 10 years pay for a single skilled tradesperson[35].

4. Feel free to look this one up yourself. Maybe not an full stomach.

5. The source for this, Robson's London Directory for 1842, also misspells Josiah's name as "Jonah", so the fact should arguably be taken with a pinch of salt.

References

1. Parish of Halesowen Bishop's Transcripts, Worcestershire Archive and Archeology Service

2. Sullivan, Janet Christine (2014): Paying the Price for Industrialisation: The Experience of a Black Country Town, Oldbury, in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, University of Birmingham Research Archive; p27

3. Ibid; p70

4. Birmingham Canal Navigation - Brindley's Old Main Line, Dudley Port Bridge, Dudley Port, www.blackcountryhistory.org; accessed 16 Jun 2025

5. Sullivan, op. cit; p72

6. Aris's Birmingham Gazette

Boat owner records: Inland Navigation - registration of boats, barges and vessels (Co. Warwick), QS/1/95, Warwickshire County Record Office

7. Inland Navigation - registration of boats, barges and vessels (Co. Warwick), QS/1/95, Warwickshire County Record Office

8. Hanson, Harry (1975): The Canal Boatmen 1760-1914, Manchester University Press; p41

9. Ibid; p58

10. Ibid; p70

11. Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 26 Dec 1803

12. Birmingham St Martin, Marriage Register 1804-1808, The Library of Birmingham

13. Birmingham St Martin, Marriage Register 1808-1811, The Library of Birmingham

14. Aris's Birmingham Gazette; 16 April 1810

15. Hanson, op cit; p59

16. Aris's Birmingham Gazette; 9 December 1816

17. Nostalgia, history and a lot of beer: These are the 10 oldest pubs in the Black Country, Express and Star (which cites as its source the CAMRA Heritage site); accessed 7 July 2025

18. Sullivan, op. cit; p90

19. Veale, Lucy and Endfield, Georgina H. (2016): Situating 1816, the "year without a summer" in the UK, Royal Geographical Society

20. Hanson, op. cit; p54

21. Ibid; p56

22. Ibid; p26

23. Trial of William Baxter, Old Bailey Proceedings Online

24. John Biers's occupation sourced from the conveniently timed baptism of his son Frederick in May 1828 St James Pentonville Register of Baptisms, The London Archives

25. Morning Advertiser (London), 14 April 1827

26. The Story of Oldbury, History of Oldbury, Langley and Worley; accessed 8 July 2025

27. The Post Office London Directory for 1835; p405

28. Barker, T.C. and Robbins, Michael (1963): A History of London Transport, Volume One, George Allen & Unwin; p22

29. Ibid; p23-24

30. Trial of THOMAS BOLTON, JAMES BARDELL, JOSEPH BARDELL, RICHARD BIRD, THOMAS BIRD, RICHARD CARPENTER, WILLIAM COWDEROY, JAMES HILL, JOSEPH JOHNSON, JOHN NEWELL, SAMUEL PEARCE, JOSIAH PARKES, PHILIP SELLICK, ROBERT TREVETT, THOMAS CORBETT, GEORGE DODD, WILLIAM GULLIVER, JOHN GOUGH, THOMAS TREVETT, EDMUND SYLVESTER, JOHN SYLVESTER, JOHN SMITH, Old Bailey Proceedings Online; p913

31. Ibid; p906-907

32. Ibid; p912

33. Ibid; p935

34. Oxford Journal; 3 October 1835

35. Currency Converter 1270-2017, The National Archives

36. Barker & Robbins, op. cit.; p393-403 (Appendix 2)

37. Pigot and Co.'s London & provincial new commercial directory; p195

38. Mayhew, Henry (1851): London Labour and the London Poor, London; accessed via Project Gutenberg, as a single plaintext file, meaning I cannot provide page numbers, but the references can easily be found by searching key words such as "scavenger".

39. Morning Herald (London); 30 January 1840

40. Perry's Bankrupt Gazette; 8 August 1840

41. Mears, Patrick E. (2023): Stone walls do not a prison make: Charles Dickens and the Debtors' Prisons, Universität zu Köln

42. Dickens, Charles (1837): The Pickwick Papers, via Victorian London

43. The Morning Herald (London); 10 Nov 1840

44. Ibid; 23 Nov 1840

45. Census for England and Wales: missing pieces, Findmypast

46. The Post Office London Directory for 1841; p507

47. The Post Office London Directory for 1843; p318

48. Robson's London Directory for 1842

49. Bucks Gazette; 9 April 1842

50. Hanson, op. cit.; p87

51. Barker & Robbins, op. cit.; p59

51. Morning Advertiser (London); 7 March 1836

52. Front Matter, 4th March 1844, Old Bailey Proceedings Online

53. Edema, Mayo Clinic; accessed 18 July 2025

54. Walford, Edward (1878): Old and New London: Volume 5, London; via British History Online

55. Pigot & Co.'s Metropolitan Guide and Miniature Plan of London, c.1820

56. Davies, B.R. (1843): London - 1843; Chapman & Hall

To go back to the Coffin-Horne tree, click here