Louisa Ann Horne 1834-1899

Early life 1834-1855

Louisa Ann Horne was born 5 October 1834[Note 1] at Goodman's Green in the parish of St Margaret’s in Westminster1, the third child of James William Horne and Mary Elizabeth Dobbs. She was probably named after her mother's sister Louisa Ann Dobbs, although the name Louisa was also present on her father's side of the family. At the time of her birth she had two older siblings, James George (born 1830) and Louis Frederick (born 1832, first name pronounced like "Lewis").

Goodman's Green, where Louisa's family lived, was part of a small community known as Palmer's Village. In that time, St Margaret's held within its boundaries an astonishgly broad cross-section of British society. At the eastern end of the parish, by the river, stood Downing Street and the old houses of parliament. A little to the west of these was a neighbourhood of such notorious poverty and criminality that it was nicknamed "The Devil's Acre", and was the subject of the first recorded use of the word "slum"2. To the north were the royal mews and part of St James's Park, with Buckingham Palace itself lying just outside the parish bounds. And nestled between the slums of Devil's Acre and the upper-class Belgravia district to the west, lay a stretch of fields and rustic buildings, a tiny corner of countryside preserved amid the urban sprawl. This was Palmer's village. The writer Charles Manby Smith (1804-1880) described it as:

...the great Babylon, where, though hemmed in all around by crowded streets, dark narrow lanes and fetid courts, it yet retained many of the rural charms of its primal condition. It had yet a village green... and on the green, every first of May, up rose, reared by invisible hands in the night, the village May-pole, round which we have seen the lads and lasses dancing to the music of their own laughter3.

There was also a blacksmith, a general shop, a wayside inn called The Prince of Orange, and by one account a "village pig" which wandered freely through the lanes and alleys4. Idyllic as it sounds, Palmer's Village was not without its critics. One writer in 1839 joked that the buildings were so uneven and ramshackle, they ought to be fined five shillings for being drunk, but said nothing about their inhabitants5.

Louisa's father was a private in the 2nd Regiment of Foot, as well as being a cornet player in the regimental band. His battalion was based in Westminster, and he does not appear to have been kept away from home very often. The decades following the defeat of Napoleon's empire in 1815 were relatively peaceful ones, and the regiment"s duties were frequently ceremonial. One of the battalions spent a year in Ireland in 1836-7, and the other was in Canada from 1838 to 1842, but Louisa's father cannot have been in either of these deployments, since they conflict with the births of her younger siblings - Mary Elizabeth (1837), George William Henry (1839) and William Francis (1841). So it seems her father either switched regiments or was exempted from serving overseas, with his status as a musician perhaps meaning he was seen as better suited to displays of pomp and pageantry in the capital. One such occasion would have been the coronation of Queen Victoria in June 18386. The spectacle surrounding this event, with a public procession from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey and thousands of visitors lining the streets, may well have formed some of Louisa's earliest memories7.

Louisa and her siblings probably attended one or more of the several free schools in the neighbourhood. The nearest was Green Coat School, named after the colour of its uniforms, which directly adjoined Palmer's Village. It was however rather small, and possibly took in only boys, as it is mentioned as having had 20 boy pupils in 1817. Only slightly further away was Grey Coat Hospital School, which had a vocational emphasis, preparing boys for apprenticeship and girls for domestic service. Also close by was the Blue Coat School, which in 1842 taught 52 boys and 34 girls. All pupils were taught reading, writing and arithmetic, with girls also being taught sewing and other household skills. Both the Grey Coat and Blue Coat schools are still standing today, and are among the few remaining pre-20th century buildings in that part of Westminster8.

Louisa's actual level of formal education was however probably quite low. For all of Louisa's brothers we have evidence of clear handwriting, with the exception of James George, but he was circumstantially very likely to have been literate. Louisa's only sister Mary Elizabeth was able to write her name as a young adult, but with a less confident hand than that of her brothers, and a couple of years later she signed with an X. The birth certificates of Louisa's children seem to imply that she signed her name, although since these are transcripts it is impossible to tell9. The only definite example we have of her signing something is from 1874 and it is with an X, so I suspect that like Mary she could at one point ready and write, but lost confidence in doing so through lack of necessity in her adult life[Note 3].

On the 1841 census we find Louisa and her siblings Louis and Mary staying with their maternal grandparents Elizabeth Myler and George Frederick Dobbs. Also in the household was Louisa's aunt (and presumably namesake) Louisa Ann Dobbs. This was still within Palmer's Village, and their parents and remaining siblings were just several doors away. The children may also have sometimes spent time with their paternal grandmother and great-grandparents, who lived very close to the village. Both Louisa's deceased paternal grandfather Joseph Horne and elderly great-grandfather James Horn"[Note 2] were former regimental bandsmen. Their mother's family however did not share the Hornes' military connections, and maternal grandfather George made book bindings for a living.

During Louisa's childhood she would have seen a substantial redevelopment of Westminster. A fire which broke out when she was eleven days old had destroyed the old medieval parliament building10, and construction of the new Palace of Westminster began in 184011. In 1845 the Westminster Improvement Act authorised a wave of demolition and rebuilding throughout St Margaret's Parish, with Britain's lawmakers apprently no longer comfortable having the notorious Devil's Acre on their doorstep. By the end of the decade residents were being turfed out, and entirely new streets would be laid down over the rubble. Being at the western reach of the parish, Palmer's Village survived a little longer, but ultimately would not be spared. According to Charles Manby Smith, who gave us such an evocative account of the village's glory days, it was now rather spoiled by an influx of cab drivers, who found the green a convenient place park their carriages. Its little streets became dirtied by piles of horse dung, and its inn became a haunt for cabbies, who were renowned for thier riotous, hard-drinking lifestyle12.

Whether it was the cab drivers, the looming threat of urban redevelopment, or some other factor, the Horne family left Palmer's Village at some point in the mid-1840s, crossing the river and resettling in Lambeth. Youngest sibling James Joseph was born there in 1847. It is not entirely clear how the eldest and youngest brothers were called by their family to distinguish them from each other and their father[Note 4]. James George was now working as a picture frame carver, but still lived at home. He had spent a brief stint in the Royal Scots guards in his mid-teens, but was dismissed after a couple of months for stealing. Louisa's mother at some point began supporting the family's income through laundry work. This in all likelihood was done from home, as piecework for middle class clients13. Louisa may have got a job as a servant during her teens (or earlier), which is what second brother Louis did.

By 1850, Louisa's father was in quite poor health. He had a persistent cough, and was bringing up catarrh. By June that year his illness was severe enough that he was given a medical discharge by his regimental doctor, and was awarded a substantial pension thanks to more than three decades of service and several good conduct decorations. He did not get to collect it for long however. The illness, identified posthumously as emphysema, continued to progress. He died at the family home, 40 New Street, near Vauxhall, on 25 September 1850.

Six months later, the 1851 census tells us that Louisa's mother had moved the family to Queen's Road, also in Lambeth. She was there with her two eldest, James George and Louis, second daughter Mary Elizabeth, and youngest James Joseph. Twelve-year-old George was working as a hall boy at the Army and Navy officer's club on St James's Square, and ten-year-old William Francis was a boarding pupil at the Royal Military Asylum, which provided education to the children of deceased or incapacitated soldiers.

The only member of the family not accounted for in 1851 is Louisa herself. She cannot be found anywhere, even when searching under name variants or outside of London. She would have been sixteen years old by this point. Whoever she was staying with, whether as a servant or a boarder, they may have misrecorded her name for one reason or another. She may even have deliberately given a false name for some reason, perhaps if she was in some kind of trouble or was staying somewhere without her family's knowledge, although there is no evidence of Louisa having any sort of falling out with family and she does not appear in any criminal records. It is also possible that Louisa was living with her mother or another relative, but that her name was accidentally missed from the household.

By 1852 Louisa's mother and the children who lived with her had moved again, this time to Marylebone. Their first address here was probably 7 Henry Street. This put them in the same neighbourhood as Louisa's aunt and namesake Louisa Ann Dobbs. Tragedy would strike the family again, as eldest sibling James George became ill, and died in Middlesex Hospital in February 1852. His cause of death was stated to be phthisis, which is an archaic term for tuberculosis. Since a tuberculosis infection can develop into emphysema14, it is possible that father and son in fact died of the same illness. Tuberculosis is a latent infection which often lies dormant, so it is possible James George had been infected by his father (or both had been infected at the same time), with James George's infection taking a little longer to progress to active disease. If this is the case it is likely that other members of the family were non-symptomatic carriers of the infection. James George was the first of Louisa's siblings to die, and was aged just twenty-one.

Relationship with Alexander Parks c.1855-c.1872

Since we cannot pinpoint Louisa on the 1851 census, we can only speculate on her life during the first half of the 1850s. However, despite not being with her mother on the census, she may have followed the rest of the family to the Marylebone area, since it was probably either there or in neighbouring Paddington that she met her partner Alexander Wilson Parks. About seven years older than Louisa, Alexander lived in Paddington, but his work as a coal porter likely took him to Marylebone. If Louisa had been working in domestic service, he may have made deliveries to the household she worked at. They are unlikely to have known each other when they were younger since Alexander had lived and worked in Paddington all his life, but she was probably familiar with men in his line of work, such as the cab drivers she would have seen when growing up in Palmer's Village. Like the cabbies, carters of every kind tended to have a reputation for heavy drinking, and it was even alleged that most coal porters saw drinking on the job as essential to their work15. We have no clue as to when Louisa and Alexander's relationship began, other than the fact that Louisa became pregnant with their first child towards the middle of 1856.

They did not marry, but lived together as wife and husband at 9 Wellings Place, near Paddington Basin canal terminal. These were tenement buildings with several families in each one. Alexander's widowed mother Martha lived several doors away, and it was at her home that Louisa's first child was born, in February 1857. The baby was given the name Martha Louisa. Two more children were born in following years, and Louisa carried on her family's tradition of giving every child one or two middle names. The first was Alexander James Louis in November 1858, followed by Mary Elizabeth in September 1860.

Louisa and Alexander's reasons for not marrying are unclear, but they were far from the only working class couple to cohabit. In fact, Paddington was known locally for having a large number of unmarried couples16, probably due to a combination of extreme poverty and a cumulative effect whereby the more cohabiting neighbours someone had the more likely they were to see it as a viable option for themselves. The rationale varied from one couple to the next, but in many cases it came down to economics. Weddings in themselves could be expensive. Married men were obligated to provide for their wives and children, and could be charged with neglect if they failed to do so. Alternatively one or both couples might feel safer without a marriage, as it meant they could walk away from the relationship when they chose without having to stand before a magistrate. Divorce had only become legal in 1857, and was still difficult to obtain. More often it was the man who was reluctant to marry, but there were cases of women not marrying if their partner had a reputation for violence, reserving the option of leaving him if he turned that aggression towards herself17.

There was precedence for cohabitation in both families. Louisa's own father was probably born to parents who were unmarried at the time. Soldiers were away from home a lot and faced a lot of uncertainty over where they would be posted next, so were thus more likely to enter into these unofficial marriages. Furthermore, the Horne family hailed from Scotland, which had somewhat more relaxed traditions around the formality of marriage18. However, Louisa appears to have been the only one of her siblings who ever had children out of wedlock. Most of Alexander's siblings also married before starting a family, but his older brother Edward lived with a woman he was apparently not married to, who had one child from a previous (also unmarried) relationship.

On the 1861 census Louisa and Alexander are at 9 Wellings Place with their three chilren. Louisa and the children all have the surname Parks, and she is listed as Alexander's wife. They share the address with two other families - another young couple with their one month old child, and an older couple with three grown-up children.

Elsewhere within Louisa's family, her mother was still in Marylebone, with James Joseph being the only child still living with her. James Joseph was now an apprentice carpenter, and his mother was still doing laundry work. Louisa's siblings Louis and Mary were both now married, the former living in Lambeth again, and the latter in Marylebone. A connection to the local cab driver's trade seems apparent, as Mary married a cabbie, and Louis married a cabbie's daughter. Mary herself was working as a seamstress, while Louis was a travelling salesman. Meanwhile the two remaining brothers were both now in the military and posted overseas.

Just days after the 1861 census, Louisa's second child Alexander James Louis became seriously ill with croup - another respiratory illness that may have tuberculosis. Aged two and a half, he was taken for baptism, presumably in a desperate bid to have the ceremony performed before he died. Strangely, although his birth certificate gives his surname as Parkes, he was baptised under the name Horne (although his father's first name is still Alexander). This perhaps suggests that Louisa, or whoever took the child to be baptised, was more afraid of lying to a priest than to a registrar! The middle names he was given at birth were seemingly forgotten, and he was baptised simply "Alexander"19. Sadly, the fear that he was close to death proved well-founded, and he succumed to the illness later the same day.

Louisa and Alexander cannot have been grieving their son long when the same thing happened with their infant daughter Mary Elizabeth. She was baptised in June 1861, this time under her full given names and Alexander's surname. The parish of St Mary Paddington Green was a busy enough one that the priest probably did not realise the discrepancy, having already carried out another six baptisms that day alone. Little Mary Elizabeth was dead within a month.

A fourth child, Henry William, was born in October 1862. He may have been named after Louisa's two brothers in the army, if George William Henry was known by his second middle name. This is the only place in either family the name Henry might have come from, although Alexander also had a brother named William. It may be that at age six months he and his now six-year-old sister Martha Louisa became ill, since both were taken to be baptised on the same day in April 1863, once again under the surname Parkes. The family were luckier this time however, and neither child died this time.

Louisa and Alexander's youngest child was born in June 1866, and named Elizabeth Alice, known to her family as Lizzie. Her middle name was probably inspired by Princess Alice, second daughter of Queen Victoria, whose marriage several years earlier to a Grand Duke Louis may have seemed especially significant to Louisa for that link to a name that appeared in her own family. Unlike the older siblings, there does not appear to have been any baptism for Lizzie under either of her parents surnames.

Two years later the family suffered one more bereavement. In July 1868 Henry William, now aged 5, was struck in the head by a falling trestle on the corner of Victoria Street and Paddington Green. He was taken to the nearby St Mary's Hospital with a fractured skull, but he did not recover. An inquest was held, and blame was levelled at the workers responsible for the trestle (who were employed by the parish), but the jury returned a verdict of accidental death38.

===Martha and Lizzie would be the only children of the five born during Louisa's relationship with Alexander to survive into adulthood. This high death rate is likely testament to the extremely impoverished conditions in which they were living, with poor sanitation, poor nutrition, and cramped housing where diseases could easily spread. The national average infant mortality rate (children dying before their first birthday) in 1861 was around 14%, with a further 14% dying between their 1st and 5th birthdays. These rates were higher still in Paddington, at 17% and 15% respectively20.

===The couple were still together at Wellings Place on the 1871 census, along with their younger daughter Lizzie, and a visitor named Emma Poole. Emma (née Moore), aged 55, was the wife of a shoemaker named Thomas Poole. The Pooles had previously both lived on Wellings Place, but were possibly now separated, as her husband was living in Westminster. Louisa's elder daughter Martha, now aged fourteen, was living in St Pancras with her cousin Mary Ann Tipper (née Pilton), daughter of Alexander's sister Hannah. Martha has no occupation listed, but she may have been doing some unpaid domestic work for her cousin's family in exchange for food and board.

Louisa was, it appears, generally well-liked within her own extended family. In 1849 her cousin James Ferguson had named one of his daughters Louisa Ann in a possible tribute to her (the Ferugson and Horne families were definitely close, with James Ferguson's brother Henry acting as a witness to William Francis Horne's wedding). Louisa's older brother Louis named his only daughter Ellen Louisa in 1870, and youngest sibling James Joseph named his eldest daughter Louisa Eliza. These last two examples postdate the beginning of Louisa's relationship with Alexander, so her unmarried status does not appear to have tarnished her standing among her family.

Relationship with Charles Finch c.1872-1882

Louisa and Alexander's relationship had possibly begun to break down in the mid- to late-1860s, since they had no children after Lizzie in 1866 despite still living together until at least 1871. The split may have been a mutual decision, and may even have been amicable, but I feel it is slightly more likely to have been instigated by Louisa. As previously mentioned, men were more likely than women to insist on not marrying, and since Louisa did subsequently marry (while Alexnader did not) she apparently was not averse to doing so with a partner who was willing.

Her husband-to-be Charles Finch was a carman - in other word a delivery cart driver. Widowed in 1871, he had three suriviving children from his first marriage - Charles Edward (born 1858), Lydia (born 1862) and Mary (born 1864), all of whom were still living with him. Once again, we have no way of knowing how early Louisa's relationship with Charles began. At the time of the marriage he lived at Townshend Cottages in St John's Wood, a street adjoining the one on which Louisa's mother and youngest brother James Joseph lived. However he had lived in Kensal New Town until at least October 187321, just five months before to the wedding, so either it was something of a whirlwind romance or Louisa knew him already. Charles's work certainly would have taken him to and through Paddington, and he had lived in Marylebone for a time during the early 1860s. The relationship could have begun as an affair when Louisa was still living with Alexander, perhaps even while Charles's wife was still alive, although I feel that if Charles's wife had been the only obstacle to them being together then they would have married sooner than they did. Alexander was almost certainly the father of Lizzie, as confirmed by DNA matches between me and descendents of his siblings22.

Louisa and Charles married on 22 February 1874 at the Church of St Stephen the Martyr, their local chapel within the parish of Marylebone. The official witnesses were Charles's sister-in-law Fanny, and her husband William Taylor (as far as I can tell no relation to Mary Elizabeth Horne's husband, Thomas Taylor). Louisa's address is recorded as Cochrane Street23, which was just a few streets from where Charles lived at Townshend Cottages. This was a new estate built to help accomodate the capital's growing population, perhaps a slight cut above Louisa's previous lodgings on Wellings Place, but it had quickly become overcrowded and was regarded as a slum24. It is not clear how long Louisa was there for or who she lived with, if anyone.

Since Alexander had never been Louisa's husband, he had no rights of custody over the children25. Lizzie appears to have remained with Louisa, although where Martha went is less clear, especially since she had already left her parents' home to stay with relatives on Alexander's side as early as 1871. We can only guess what the girls thought of their parents' split and their new step-relatives, and whether they continued to see anything of their father or their other relatives on his side of the family. Lizzie at least seems to have had a fondness for her father, since she would later give her eldest son the middle name Alexander. She did not make a similar tribute to Louisa when naming her daughter.

As for Alexander himself, he does not seem to have fared well following the breakup with Louisa. He died at Kent's Place, another crowded tenement row near Paddington basin, in November 1875, twelve hours after suffering a stroke. Risk factors which may have played a part include poor diet, tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption26. The death certificate describes him as having "formerly" been a coal porter, so he presumably had already had to retire through ill health, or perhaps lost his job for some other reason. The death was reported by a brother who lived nearby, and there is nothing in particular to indicate that he had found someone else following Louisa's departure.

Louisa and Charles settled in Kensal, close to where Charles had lived before being widowed. They had two children together. The first was born in 1875 and named Henry William. Like his brother of the same name, he did not live to see adulthood, dying around a year old. The second, Ada May, was born in April 1877.

These were times of change for others in Louisa's family. In 1870 her sister Mary Elizabeth had departed with her husband and children for a new life in the United States. They lived in Ohio for some years, and then Delaware before returning to England in around 1878. In 1873, Louisa's brother George William Henry was sent home from India with a medical discharge. He was suffering from advanced syphillis, and died the following year27.

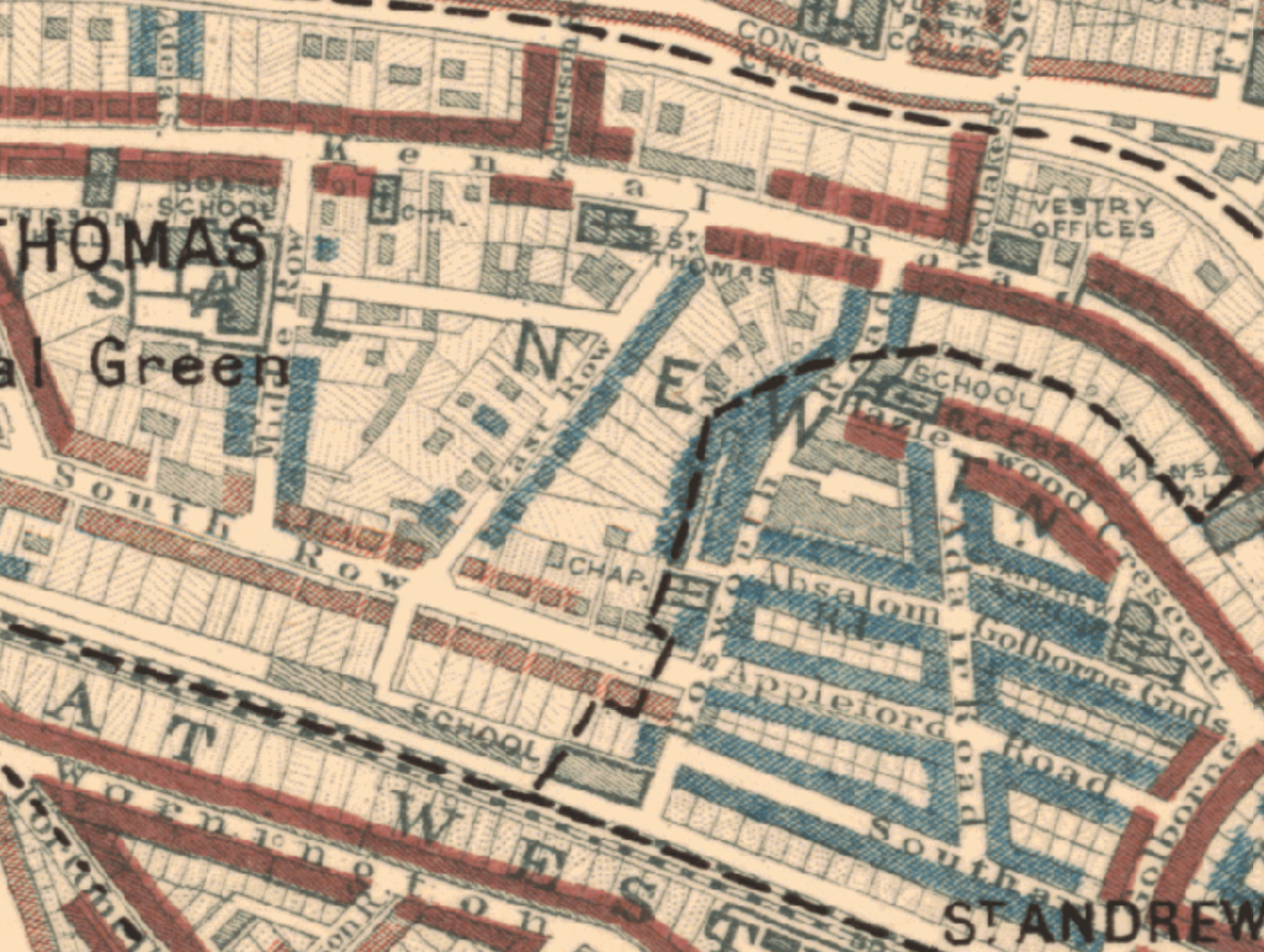

In 1880 Louisa's daughter Martha married a cab driver and jack-of-several-trades named John Connell. However at the 1881 census Martha is living with Louisa and Charles at their home on East Row, Kensal Town, her husband's whereabouts unclear. Also in the household are Charles's children from his first marriage, Lydia and Mary (the elder child, Charles, having married and moved out two years earlier), Louisa's daughter Lizzie, and the youngest daughter, Ada. East Row was in yet another newly-developed yet overcrowded and run-down neighbourhood28.

Whether or not Louisa's relationship with Charles was happier than her one with Alexander, it did not last as long. Charles died in Spring 1882, at the age of fifty-three.

Later Life 1883-1899

Louisa became a grandmother in 1883, one year after her bereavement, when Martha's first child Mary Emily was born. The reason for Martha's husband's absence in 1881 is still not explained, but the separation was evidently not permanent. Louisa's address was now Park Terrace, which appears to have been another part of East Row. Her daughter Martha lived several doors away, as did a couple named Henry and Louisa Wright, who had been next-door neighbours of Louisa on East Row. Henry Wright had probably been an acquaintance Charles[Note 5] , and both he and his wife seem to have remained friends of Louisa and her family. Shortly after Mary Emily's birth she, the Wrights' child Henry Frederick, and Louisa's now six-year-old daughter Ada were all taken for baptism on the same day at All Saints Church in Notting Hill29.

It is not known if Louisa's stepdaughters Lydia and Mary lived with her for any length of time following their father's death, but they certainly did not go far. Lydia was living on nearby Kensal Road at the time of her marriage in 1886, at the same address as the man she was marrying. Mary is stated to be living in the same parish at the time of her wedding a year later, but no exact address is given. The eldest living Finch sibling, Charles Edward, was also just a few streets away on Hazlewood Crescent. None of their other relatives are known to have lived in Kensal.

Lizzie must have moved out of her mother's home at some point too, as by 1887 she was living on Southam Street, which is also very close to East Row. That year she married a wood turner named Alfred Coffin who lived several doors from her, and the two of them settled some miles away in Fulham shortly after their wedding. It perhaps did not go down too well with Louisa when they named their first child Alfred Alexander.

In 1891 we find Louisa still at Park Terrace, in what the census reveals was a dwelling above a grocer's shop. Like her widowed mother before her, she was now working as a laundress, but whereas her mother had probably worked on her own account, Louisa was an employee. There were in fact quite a large number of laundry businesses operating in Kensal, many of them advertising a collection and delivery service in local newspapers30, something which no doubt provided a lot of work to the district's many carmen. It is hardly surprising, with the predominantly upper class residents of Kensington and Chelsea to the south, that the adjacent working class neighbourhood was providing outsourced domestic labour to their wealthier contempoaries.

George Duckworth's notebooks, compiled in 1899, would paint the following picture of Kensal Town's squalor, comparing it unfavourably with the middle-class Queen's Park Estate across the canal:

"The whole town is on the south side of the Grand Junction Canal & on a much lower level - physically, morally, socially & intellectually than the Queen's Park Estate [...] There is the indefinable smell of dirt in the Kensal Road, & a dust yard on the canal bank which fills the air with beastliness [...] [police sergeant] Hawkes says the inhabitants are not vicious but 'low'"

On East Row itself, Duckworth mentions a particularly foul-smelling shed used for drying fish skins, which were exported to France for refining champagne. On a neighbouring street he states that there is "plenty of drinking" but "no trouble to the police". He even makes reference to the rather lax approach to marriage among the working class of this part of London, noting that there was "no prostitution, but loose relations". There were also a large number of religious buildings, with Duckworth remarking that "Kensal New Town is a happy hunting ground for missionary effort"31.

The only other member of Louisa's household on the 1891 census was her eight-year-old granddaughter Mary Emily Connell. Conversely, Ada was living with Martha's family, who were now in Marylebone. Martha and her husband John were apparently now making good money running a cab stand, and they could even afford a live-in domestic servant. Ada's occupation is listed as "cook", although it is not clear if she was doing this for her sister's family or working elsewhere. That Louisa had a young child living with her suggests she probably did the bulk of her laundry work from home. Kensal New Town does not seem to have been an ideal place for Mary Emily to live, but the arrangement would have reduced Martha and John's childcare needs and given them more time to devote to their business, whereas looking after her young grandchild probably gave Louisa a sense of comfort and belonging within the family. Then again, Mary Emily may have only been with Louisa on a short term visit which happened to coincide with the census date. Even so, it clearly demonstrates the close contact between Louisa and her eldest daughter's family, and a willingness to share childcare responsibilities.

At some point between 1892 and 1896 (probably closer to the latter), Lizzie moved back to Southam Street with her husband and three children. They had probably run into some financial difficulty, since it was a far poorer neighbourhood than the one they had left behind in Fulham32. It is however not clear if Louisa was still living in the neighbourhood at that time. Her next known whereabouts were in Willesden, around two miles northwest of Kensal.

She was probably taken in by her brother James Joseph, who lived with his family in Willesden. Their older brother Louis Frederick also lived quite nearby in the Child's Hill area of Hendon. He had been living alone since at least 1891, for which he apparently had no one to blame but himself. In 1887 he spent a week a custody, having assaulted his wife Mary Ann by throwing a large piece of wood at her33. Unsurprisingly Mary Ann had left him, and moved in with their eldest son. This was evidently not the only unhappy marriage in the Horne family, as Mary Elizabeth was by now living separately from her husband. It seems that only the two youngest brothers William Francis (who now lived in Lambeth) and James Joseph had remained in stable marriages.

Death and Legacy

Louisa died at Hendon Union Workhouse, Edgware Road, on 12 May 1899. I have no record to indicate how long she had been in the workhouse before her death, only that she was living in Willesden beforehand. Willesden had separated from Hendon Union in 1896 due to a burgeoning population, but its workhouse was not built until 190034, and so Louisa would have been sent to the overcrowded Hendon establishment even if she was admitted shortly before her death.

That she went there at all indicates she was probably in extremely poor health, to the extent that she could no longer work and her relatives were unable to see to her needs. The workhouse was the closest thing to a hospital or a care home for working class families before the existence of the welfare state. I would imagine that if Louisa had been more able, at least one of her relatives would have given her a home. Having said that, it does seem that some of Louisa's next of kin were not doing so well as they had been a decade earlier. As previously noted, Lizzie had returned to the tenements of Kensal. Martha and her husband were no longer employing a servant. Ada's whereabouts during this time are unknown. She cannot be found on the 1901 census. She resurfaces in 1903, when she married John James Green. Her daughter born in 1906 would be named Kitty Louisa, the only one of Louisa's grandchildren to bear her name.

Louisa's cause of death was cerebral haemorrhage - in other words, a stroke, the same thing that killed Alexander. She was 64 years old. The death was reported by her son-in-law, John Connell, which would seem to indicate that family members were taking an active interest in her welfare in her final days, since this normally would have been the duty of the workhouse master. She was buried at Kensal Cemetery35, which further proves the involvement of family and makes it more likely that her stay at the workhouse was necessitated by ill health alone, since any deceased inmate whose family were unable or unwilling to arrange for a private funeral would be buried in workhouse grounds36. They could nevertheless only afford a low-cost communal plot, and she was buried with three unrelated individuals who had died around the same time.

The burial record gives us one final and slightly cryptic clue regarding Louisa's standing with her daughters. Her abode is listed as 60 Southam Street, which was Lizzie's address at the time. Both the death certificate and workhouse register clearly state that Louisa's previous place of residence was in Willesden, so the implication here is that Lizzie was involved in the funeral arrangements, and either mistakenly substituted Louisa's last address with her own, or perhaps deliberately gave her own address since she was the only first-degree family member then living in the borough the cemetery was attached to. Another possibility is that Louisa had been living with Lizzie's family on Southam Street for some time during the 1890s, only staying briefly with her brother in Willesden before entering the workhouse. This presents us with a rather upsetting scenario, in which any tensions between Louisa and her middle daughter had thawed out, only to flare up again prompting Louisa to move in with her brother, whereupon a serious decline in health put her in the workhouse, from which she never returned. A more positive interpretation is that she became ill while at Southam Street, and was sent to Willesden where the air was perhaps a little cleaner and her brother's family was maybe more able to look after her. However Lizzie does have a documented history of unkindness towards her family members, for example charging an extortionate rent to a niece who lodged with her, and even disowning her own daughter over a request for money. With all this in mind, I do regretfully lean towards the more pessimistic scenario, with mother and daughter parting on bad terms. As with so many details of Louisa's life, the truth behind the evidence will probably never be known.

This final story is not Louisa's, but it makes a happier coda to her history than the one above. Ella, Martha's youngest daughter who was charged rent to live at Lizzie's house, became very close with Lizzie's daughter Lillie. Ella emigrated to New Zealand in the 1920s, but the two cousins continued to correspond with each other, and when Lillie was disowned Ella was for some years her only family member who kept in contact. This closeness continued into the following generation, with Ella's daughter visiting Lillie's son (my grandfather) on a trip to Europe in the 1950s, but the two branches of the family lost touch after my grandparents passed. Having met her as a child, my dad recalled Ella's daughter's name and knew she was important to his family, but was not sure how she was related. Luckily this was enough of a clue for me to track down Ella's granddaughter, and since 2015 descendents of Martha and descendents of Lizzie are once again in contact. At the time, I did not know who Lizzie's parents were, since her father was wrongly recorded as "Alexander Horne" on her marriage certificate, with her birth certificate being under the name Parkes. Ella's relatives however knew Martha's name, and between us we were able to piece together this part of the family history. Were it not for that bond between two of Louisa's granddaughters that began over a century earlier, then we may never have found Louisa at all.

Notes

1. There is some confusion over Louisa's actual age. The date of 5 October 1834 is from her baptism entry, recorded five months later. Census recordings 1841-1871 however imply she was born 1837-39, with the censuses of 1881 and 1891 reducing her age even further, implying a birthdate in 1840-41. Finally her burial record states she is 64 (which is accurate if she was born in October 1834), while her death certificate takes a year off, suggesting she was born 1835-36. It was very common for people in this period to lose track of their age, with underestimates occurring more frequently than overestimates (for comparison, her sister Mary's implied birth year on census records fluctuates even more wildly, from 1833 to 1843). However it is very strange that Louisa is recorded as being three years old on the 1841 census, since while it may be easy for an adult to lose three years, it seems unlikely that a family would make the same mistake in regard to a six-year-old child. I have considered the possibility that the Louisa Ann baptised in 1834 died in infancy, and that a second Louisa Ann was born in about 1838 with no surviving baptism record. I find this unlikely however for a number of reasons. Firstly, there is no burial record for an infant Louisa born in 1834. Secondly, there is very little time for a hypothetical second Louisa to have been born in between her siblings Mary (born Summer 1837) and George (born Summer 1839). Births to the same mother a year or less apart are possible but rare, and three births in a two-year period would be highly unusual. Finally, all but one of Louisa's siblings has a surviving baptism record. The one who didn't was James Joseph, the youngest by a considerable margin and born in a different place to the older siblings. A second Louisa Ann could of course be a twin of either Mary or George, but this begs the question of why she was not baptised at the same time as her twin. I think on balance it is far more likely that the Louisa born in 1834 is our Louisa, and that a mistake was made on the 1841 census. This is perhaps reinforced by the fact that whereas it was normal for children to be listed in age order, Louisa is listed first (with stated age 3), above her brother Louis (age correctly stated as 8), with sister Mary (age correctly stated as 3) last. The order is wrong whether we go with the one-Louisa or two-Louisas theory, but the fact that it is definitely out of order suggests there may have been some mix-up when conveying the information to the enumerator or by the enumerator themself. Perhaps Mary's age was accidentally duplicated for Louisa's.

2. Since no baptism records exist for Louisa's father James William Horne or her (assumed) grandfather Joseph Horne, it is difficult to be certain of exactly how they are related, but James William being the son of Joseph, and Joseph being the son of James is currently my best guess. There is little doubt that they were somehow related, and that various members of the extended family kept in close contact. See James William and Joseph's pages for more information

3. Another possibility is that, since this was Louisa's marriage record and her husband was apparently illiterate, she deliberately signed with an x so as not to embarrass him.

4. None of the children nor their parents appear to have been known by their middle names, and in fact these middle names tend to appear on a minority of records. James George is just called James on the two census records he appears on, and he seems unlikely to have been called George as his brother George William Henry is just called George on the census as well. James Joseph may have been called Joseph, but on later records he is generally James J. or just James. However there is some conflicting evidence over James Joseph's name, since he is called Frederick on the 1851 census, and does not appear in the records as James Joseph until 1853. This could be a simple error, but it could also be that he was originally called Frederick Joseph (for example) and renamed after his brother James George died in 1852. Since he is the only one of the children with no baptism record (and like all the children, has no birth certificate), it is impossible to tell what he was originally named. Another possibility is that James George and James Joseph were in fact known by their middle names, and that George William Henry was known as Henry. It could be that the children's full names were given to the enumerators, but only the first names were actually recorded on the census. This is perhaps supported by the fact that Louisa would name two of her children (the first dying in infancy) Henry William.

5. Henry Wright was also a carman and was lodging with Charles's in-laws Fanny and William Taylor in Marylebone in 1871. These were the same Fanny and William who witnessed Louisa and Charles's wedding in 1874, and with whom Charles may have been living at the time. Louisa Wright's maiden name was Allum. Mary Elizabeth Horne's daughter Ida May married a Benjamin Allum. However I can find no relationship between the two Allums (they were not siblings, and since both their fathers were named William they cannot have been first cousins), so this is probably just a coincidence.

References

1. Registers and books of St Margaret’s Church, Westminster, The Dean and Chapter of the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter in Westminster

2. londonist.com; accessed 30 Jun 2023

3. Keegan, Vic (2019): Vic Keegan's Lost London 122: Palmer's Village – Westminster's piece of Merrie England

4. Daily News (London), 11 Aug 1902

5. Northern Whig, 25 May 1839

6. English Chronicle & Whitehall Evening Post, 26 June 1838

7. Strong, Roy (2012): Queen Victoria's Coronation, www.queenvictoriajournals.org

8. Historical Notes on Westminster Schools, Westminster City Council

9. Marriage registers, St Stephen the Martyr, Hamstead, London Metropolitan Archives

10. UK Parliament website, accessed 13 Jul 2023

11. Ibid, accessed 13 Jul 2023

12. Abandoned Communities, accessed 13 Jul 2023

13. The Washerwoman's Genes, accessed 13 Jun 2023

14. Jin, Jianmin; Li, Shuling; Lio Xiaofang; and Sun, Yongchang (2018): Emphysema and bronchiectasis in COPD patients with previous pulmonary tuberculosis: computed tomography features and clinical implications, Dove Medical Press Ltd

15. Mayhew, Henry (1850), Labour and the Poor, the Morning Chronicle; via Victorian London, accessed 14 Jul 2023

16. Frost, Ginger (2008): Living in Sin: Cohabiting as Husband and Wife in Nineteenth-Century England Manchester University Press; p130

17. Ibid; p127-129

18. Ibid; p16

19. St Mary Paddington Green baptism registers, London Metropolitan Archives

20. Populations Past, accessed 28 Jun 2023

21. Bayswater Chronicle, 1 November 1873

22. www.ancestry.co.uk/dna/; accessed 14 Jul 2023

23. St Stephen the Martyr, Hampstead, marriage registers 1856-1875, London Metropolitan Archives

24. St John's Wood Conservation Area Audit, Westminster City Council

25. Frost (2008); p35

26. Boehme, Amelia K; Esenwa, Charles; Elkind, and Mitchell S. V. (2018): Stroke Risk Factors, Genetics, and Prevention, National Library of Medicine

27. Chelsea Pensioners' British Army Service Records 1760-1913, National Archives

28. Hidden London, accessed 15 Jul 2023

29. All Saints Notting Hill, baptism registers 1861-1899, London Metropolitan Archives

30. West London Observer, 23 August 1890; amongst many similar examples

31. Duckworth, George H (1899): Notebook: Police District 23 [St Mary Paddington and Kensal Town], London School of Economics

32. Ibid

33. Hendon & Finchley Times, 20 Feb 1887

34. workhouses.org, accessed 15 Jul 2023

35. Records of the General Cemetery Company, Kensal Green, London Metropolitan Archives

36. workhouses.org, accessed 15 Jul 2023

37. Charles Booth's London, London School of Economics, accessed 15 Jul 2023

38. Marylebone Mercury, 18 Jul 1868

To go back to the Coffin-Horne tree, click here