William Dobbs c.1673-1726

Early Life and Apprenticeship 1673-1697

William Dobbs was probably born in or near the town of Windsor in Berkshire. His birth year of approximately 1673 is assumed from later events[Note 1], since no baptismal record of him can be found. His father was a saddler, also named William. Little else is known about William's early life. He was educated, formally or informally, well enough to read and write. He had a brother named Thomas, baptised in 1685. An Avis Dobbs who died in Windsor in 1731 may have been his sister, or possibly his mother. There are burial records for a William Dobbs in 1685 and 1694, presumably one of whom was our William's father. The other may have been his grandfather or a cousin.

Windsor is now best known for its castle, but in the early-modern era it was also renowned for the poverty and squalor of its less royal inhabitants. The Annals of Windsor mention streets filled with "dunghills, tubs, empty barrels, corrupt or stinking fish, feathers or herbs that may annoy the said streets with unwholesome smells". In 1683 a town by-law was established compelling householders to clear the space in front of their property every Saturday afternoon. Residents were also responsible for a simple form of street-lighting, hanging candles outside their homes every evening during the winter months[2].

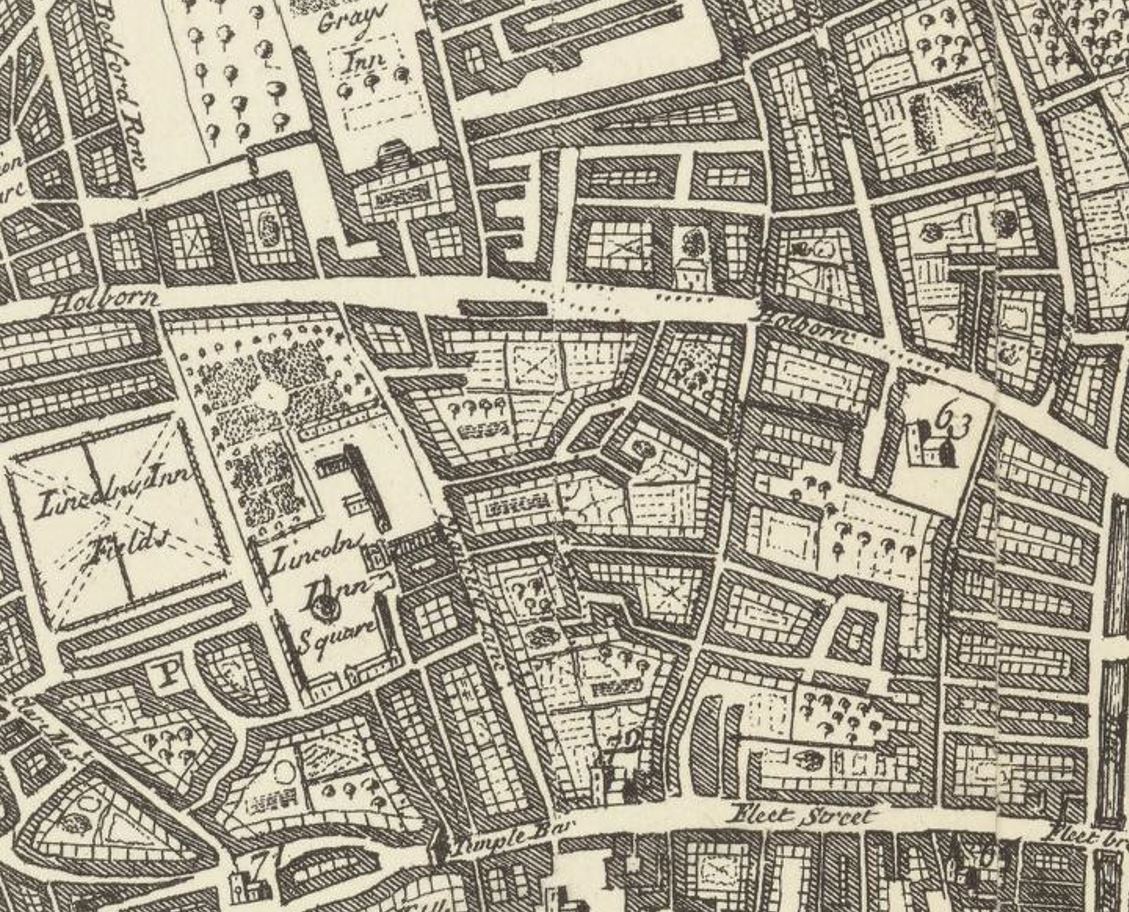

Apparently unable or unwilling to find suitable employment in his home town, William headed to London in his mid-teens. In January 1690 he became apprenticed to Thomas Gery[3], a poulterer of Red Lyon Court[4] off Fleet Street. He was formally presented to the guild on 17 February for registration, and bound to Mr. Gery for a period of seven years. As was customary at the time, he probably lodged with his master, and became a part of his household[5]. There were typically around twenty-five new apprentices bound to a poulterer in London each year, with each master being allowed a maximum of two at a time[6], although Mr. Gery apparently had none besides William.

The poulterer's trade primarily involved the sale of poultry, gamebirds, and other small animals for the meat markets. Contemporary price guides list such diverse birds as ducks, turkeys, herons, pheasants and pigeons, as well as rabbits, as falling under the poulterer's remit[7]. Technically they could also keep and breed the animals in question, but this was rare, and most London poulterers would buy from breeders and hunters outside the city[8]. Once acquired, Gery's animals would likely have been sold at the nearby markets at Newgate and Honey Lane[9].

This work also brought William into contact with 16-year-old Isabella Willimott. Isabella came from a middle-class landowning family from Garthorpe in Leicestershire. Her uncle Robert Bullivant was also a poulterer, living at the western end of Fleet Street. She may have lived with her uncle, perhaps working for him as a household servant, or through him she may have become a servant to William's master Thomas Gery. At any rate, Mr. Bullivant was certainly known to William, as he provided testimony for the start of the latter's employment with Mr. Gery[Note 2].

The standard contract for London apprentices was quite strict, and as well as swearing off such vices as taverns and theatres, they were also not allowed to "commit fornication"[10]. This stipulation apparently did not stop William and Isabella, although their relationship probably began before William was even formally bound, since their first child, Mary, was born no later than mid-September 1690. This tallies with the fact that Isabella's uncle was the witness for the start of William's employment in January. William had perhaps lodged with Mr. Bullivant, and then been referred by him to Mr. Gery.

Mary was baptised at the church of St Bride's Fleet Street, and the record for this stated that Isabella was William's wife, despite this not being the case[Note 3]. Both William's master and Isabella's uncle lived in the neighbouring parish of St-Dunstan-in-the-West, so it seems probable that the young couple decided to have Mary baptised somewhere their faces were not known, and they could more easily pull off the ruse of being a married couple.

Isabella could of course not have hidden the pregnancy and birth from those around her, but if Mr. Gery got an inkling that his apprentice was the baby's father, it does not seem to have affected William's career. Both the apprenticeship and the relationship would continue, but William and Isabella may have been more careful to avoid pregnancy (or were perhaps prevented from seeing each other), since their second child was not born until 1694[Note 4]. She was named Isabella, and again was baptized at St Brides in a record which states her parents were married.

Husband and Freeman 1697-1827

William's apprenticeship would have come to an end at the beginning of 1697. Now finally free of his contractual prohibitions, he and Isabella married at Gray's Inn chapel on 29 August that same year[11]. Officially the chapel was for the barristers who lived at the inn, so this may have been another case of the couple finding a place where they were not well known. The chapel was apparently in a "ruinous" state and would be rebuilt the following year[12]. William is described as "a poulterer next Temple Bar".

Temple Bar was an imposing gatehouse at the western end of Fleet Street that marked the boundary between the cities of London and Westminster. In 1672 it had been rebuilt in the English baroque style, with a design attributed to Christopher Wren. It was a rather grisly monument in William's day. In 1684 half the torso of Sir Thomas Armstrong, hung, drawn and quartered for his part in the Rye House Plot, was placed atop Temple Bar, after having been boiled in pitch to ensure preservation. In 1696 Armstrong's remains were joined by the heads of Sir John Friend and Sir William Parkyns, similarly executed for their parts in a plot to assassinate William III. The display of traitors' body parts on the gates of London was a tradition going back centuries, and fresh heads would be periodically added to Temple Bar until 1746[13].

It was probably during the Autumn of 1697 that William was admitted into the Worshipful Company of Poulters. Membership of this guild allowed him to trade in birds and rabbits within seven miles of the City of London[14]. To gain entry he would have been subject to fees of 5 shillings and sixpence, and by tradition an additional 13 shillings and fourpence to pay for a silver spoon with his initials engraved on it[15]. These costs, equivalent to approximately £101 in 2017[16], may explain why he was not admitted immediately upon completion of his apprenticeship. At his admission ceremony he would have had to swear a lengthy oath. The following is the text of the oath as it was during the reign of William and Mary, although since Mary had died by the time of William's admission it had presumably been amended accordingly:

You shall Swear you shalbe true and faithfull to our Soveraigne Lord and Lady William and Mary King and Queene of England you shall be obedient at all times hereafter in all matters Lawfull to the Master and Wardens of the Art and Mistery of Poulters London and to theire Successors for the time being You shall not withstand or disobey the Summons of the Master and Wardens of the said Mistery for the time being by theire Officer therefore assigned without you have a lawfull and reasonable excuse And for your owne part you shall well and truely observe performe fulfill and keepe all and singular the lawfull and reasonable Orders and Ordinances made and to bee made by the said Master and Wardens and Assistants of the said Mistery for the good Rule and Government of them and theire Successors and shall not doe anything to the damage prejudice or rebuke of the said Master Wardens Assistants and Comonalty but in these things and in all other things you shall doe use and behave your selfe as a good Citizen of the City of London and a Freeman of the said Company ought to doe Soe helpe you God[17]

To further impress the significance of these words on its members, the Company's motto was quite simply "Remember your oath".

In common with all of London's livery companies, admission to the Poulterers' Company enabled its members to apply for Freedom of the City of London. Doing so was in fact an obligation, and all new freemen had three months to acquire that status, or face a fine[18]. William gained his on 10 December 1697. Freemen of the City were then further enabled to become liverymen of their Company, following payment of a rather hefty fee of £20 (£2140 in 2017). As with Freedom of the City, becoming a liveryman was as much as expectation as it was a right, since fines were imposed for memebers who could afford the livery but did not take it[19]. William did indeed become a liveryman by at least 1710, since he voted in a general election in that year, something he would only have been able to do if enfranchised by taking the livery[20].

Despite having completed his apprenticeship and obtained his "Freedom", another regulation of the Company prevented him from immediately setting up his own poultering business. First he had to serve a minimum of one year as journeyman, working as an employee for an established poulterer. Typically this would be with the same master with whom he served his apprenticeship[21]. However, the note on William's marriage record that states he was "next Temple Bar", makes me suspect that he served his time as journeyman with Isabella's uncle Robert Bullivant, since the latter was also based by Temple Bar.

Tragedy hit the family in December 1698, when William's second daughter Isabella died at the age of four. They were still living on Fleet Street at this point. Robert Bullivant had relocated to Islington earlier the same year[22], so it seems plausible that William had taken over his old premises.

William may however have opened a second shop, as by 1700 the Dobbses were living on High Holborn, a few minutes walk to the north of Fleet Street. Here their third (and first legitimate) child was born, and named Avis. This relatively uncommon name probably came from William's side of the family, either the name of his mother or a sister, as evidenced by a burial record of an Avis Dobbs in his home town of Windsor.

A few years later however they were back on Fleet Street, where sons Stephen and Richard were born in 1702 and 1705 respectively. These names may have come from William's side of the family, or they be chosen for some other reason; they do not come from Isabella's side. The Dobbses were then back on High Holborn for the births of William in 1707 and Isabella in 1708, before finally returning to Fleet Street for the births of youngest children Thomas in 1709 and Ann in 1711. These repeated moves back and forth between the two streets, no more than 500m from each other, makes me wonder if William perhaps maintained premises at both, and alternated between which he and his family lived at.

Another member of this growing household would have been William's own apprentice. His first was named John Wrightington, bound to William in 1701[23]. He was followed by James Oakes, bound in 1703. There is no record for John's admission to the Company of Poulters, so rather than having two apprentices simultaneously, William's contract with his first apprentice may have been ended early for one reason or another. On the back of the indenture contract for James Oakes is a note indicating that William had promised to pay the boy the sum of £5 towards a suit at the end of his tenure[24].

The Dobbs poultering business was probably not run by master and apprentice alone. Another of the Company's restrictions was that Freemen were only allowed to give full time employment to an apprentice, a journeyman, or their own children[25], and we can assume that William took advantage of this last caveat. Eldest sons Stephen and Richard would grow up to become poulterers in their own right, and since they were not apprenticed to anyone must have learned the job at home. William's wife Isabella clearly also took a major role in running the business, as evidenced by the fact that she would continue to work as a poulterer and train apprentices after her husband's death.

In 1708 William's firstborn child Mary died, at the age of seventeen.

In 1710 we have the earliest record of William exercising his right to vote. In the general election of that year he cast his vote for Richard Hoare, William Withers, John Cass and George Newland[26][Note 5]. These were the Tory candidates for the city, and all four were returned as members of parliament, defeating their Whig opponents. Having originated less than thirty years previously, the Tories were then more of a parliamentary faction than a formal party, one built around vocal support for monarchy, tradition, and the established church[27]. A more pointed example of the kind of men William was voting for is that two of them (Withers and Cass) were officials in the Royal African Company, an organization which every year transported thousands of men and women from Africa to be sold as slaves in the New World, with the company's initials burned into their chests with a red hot brand[28][Note 6]. We cannot know the extent to which William was aware of these horrors, but there was such heavy involvement from London's livery companies in the transatlantic slave trade and a large part of the city's wealth was generated through it[29], it seems inconceivable that he would not have had at least some knowledge of slavery and how it indirectly benefitted him.

As a liveryman, William would have been required to wear his livery gown on election day, as he would have done at all civic and official functions. As with so many aspects of life in the Poulterers' Company this was governed by stringent rules. "For decency and civility", the clothing worn with the gown had to be black or another "sad colour", and in 1684 the Company had fined a poulterer 12 shillings for "wearing a white hat"[32]. Heaven forbid that someone be improperly dressed on their way to cast a ballot for slave traders.

The 1710 election also took place against a backdrop of violence closer to home. In November 1709 the Tory Anglican minister Henry Sacheverell gave a vitriolic 90-minute sermon attacking relgious dissenters (primarily Presbyterians) and claiming that the government's tolerance towards these dissenters was undermining the church. He was impeached by the Whig-led House of Lords for casting aspersions on the Glorious Revolution and the Act of Toleration, and banned from preaching for three years[33]. During the trial his supporters took out their frustrations on the Presbyterian community, and in February 1710 they rampaged through the city chanting "High Church and Sacheverell!", ransacking and burning Presbyterian chapels and making a huge bonfire on Lincoln's Inn fields[34]. We cannot prove that William was involved in these events, but being a Tory voter who lived just a few minutes' walk from Lincoln's Inn, it does not seem improbable.

Surviving poll books show William voting again in the elections of 1713[35] and 1722[36], both times placing his vote for the Tory candidates. Aside from this, few events are attested from his later life. He took on another apprentice, a 14-year-old from Hertfordshire named Joshua Turner, in 1716[37]. In 1717 his youngest child Ann died, aged five. In 1723 his third son, William, was apprenticed to a vintner. It was perhaps assumed that Stephen and Richard would inherit half of the poultering business each, compelling younger son William to find an alternate trade. Fourth son Thomas may have died during childhood, since I can find no record of him as an adult.

Towards the end of his life William was living on High Holborn again. He died in the summer of 1726, aged approximately fifty-three. Despite dying in Holborn, he was buried at Fleet Church Yard, St Dunstan-in-the-West, on 3 July[38].

Legacy

No surviving will can be found for William, either in the London Archives' wills collection or the Court of Canterbury register of wills. This may indicate that the death was sudden and he had not had time to draw up a will, or it may be that he did not expect any disputes in how his property was divided. It appears that Stephen took over the running of the premises at High Holborn, as most records show him there, whereas Isabella and Richard appear to have run the premises by Temple Bar. Just six months after her husband's death Isabella had taken on a new apprentice. She would train two apprentices before her death in 1742.

All of William's surviving children were eligible to join the Worshipful Company of Poulterers by the time they turned twenty-four, by right of patrimony. Stephen and Richard did so, albeit waiting until they were thirty and twenty-nine respectively. Having completed his apprenticeship, third son William was eligible to join the vintner's company, but chose to join the poulterers' instead, doing so aged thirty-five whilst working as a vintner. The guilds were at their peak in William Sr.'s day, but by the mid-eighteenth century the growing suburbs were threatening the City's monopolies, and joining a livery company came with less prestige and influence than it had a generation earlier[39].

Freedom of the City did still bestow upon its holders the right to participate in general elections, although of William's children only Richard is known to have done so, in 1749. In what might have been a huge disappointment to his father had the latter been alive, he gave his vote to the Whig candidate.

None of William's children married during his lifetime, and only Avis and Richard are known to have done so at all. Richard named his second son William, but the child died in infancy. He would later give a younger son the same name, but this child also died young. Avis had only daughters. Aside from appearing as the middle name of one of Richard's grandsons, the name William faded from the family within a few generations.

Notes

1. Primarily from his year of admission into the Freedom of the City of London, for which applicants had to be aged 24 or over. His indenture as an apprentice in 1690 also arguably supports this assumed birth year, since the average age of new apprentices at the time was between sixteen and seventeen, although this was itself influenced by the minimum age for freemen of the city, since an apprenticeship usually lasted seven years[1].

2. A barely-legible note written in Latin on the back of William's indenture record seems to be referring to this. I can only decipher around half of the words, but it has a date of January in the first year of the reign of William and Mary (1689-90), mentions a witness ("testio"), and is signed R. Bullivant.

3. Apprentices were also forbidden from marrying which, compared to fornication, is generally somewhat more difficult to do in secret.

4. There is some circumstantial evidence that another child named Robert was born around this time, but for some reason has no surviving baptismal record (perhaps being baptised under a false name due to illegitimacy). If so, he would presumably have been named after Isabella's uncle Robert Bullivant. The evidence for this child is as follows:

- A Robert Dobbs was named as executor of the estate of William Dobbs Jr. (son of the William Dobbs featured in this document). William Jr. is not known to have had any children of his own, and without a will naming any alternative his executor would have been his eldest surviving sibling.

- Richard Dobbs's son John used the names of several of his uncles and aunts when naming his own children. Once of these children was called Stephen Robert Dobbs.

- In 1721 a Robert Dobbs married Elizabeth Convers at Lincoln's Inn Chapel (close to where our Dobbs family lived, and reminiscent of William and Isabella marrying at Gray's Inn). His first child was named William and born in Holborn, where our Dobbs family lived at the same time.

Note that if this Robert Dobbs was indeed the son of William and Isabella and born prior to his father's admission to the Poulterers' Company in 1697, he would not have been eligible to join said Company by right of patrimony, since this required his father to have been a member at the time of his birth. This would explain why he did not join the company whereas his younger brothers did. However since the existence of this Robert in the family is not confirmed, coupled with the fact that there is little to be said about him besides what is written in this footnote, I have completed this biography of William Dobbs on the assumption that he did not exist.

5. There were at the time four MPs representing the City of London, and each voter was allowed four votes to choose their preferred candidates. Since the Tories and the Whigs each fielded a group of four, there was a total of eight choices. Most voters would place all four of their votes with the one group or the other, but a small number would split their vote between the two factions. The ballot was not secret, and until the Ballot Act of 1872 it was completely normal for the authorities to publish a complete list of who had voted for whom[30]. These lists have not always survived so the elections mentioned here are not necessarily the only ones William took part in.

6. It should also be pointed out that, although Tories seem to have been be more heavily represented amongst Royal African Company associates, there were certainly more than a few RAC officials and shareholders amongst the Whigs too. These include Anthony Ashley Cooper, one of the party's principle founding members, and "father of liberalism" John Locke[31].

References

1. Wallis, Patrick; Webb, Cliff and Minns, Chris (2009): Leaving Home and Entering Service: The Age of Apprenticeship in Early Modern London London School of Economics; p5-6

2. Ditchfield, P.H. & Page, William (eds) (1923): A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3, Victoria County History; p56-66; accessed via British History Online 6 Nov 2024

3. Freedom Admission Papers, 1681-1930, The London Archives

4. Land Tax Records, Farringdon Without 1692, The London Archives

5. Wallis et al (2009); p12

6. Jones, P.E. (1981): The Worshipful Company of Poulters of the City of London (Third Edition), Oxford University Press; p50

7. Ibid; p149

8. Ibid; p95

9. Ibid; p83

10. Freedom Admission Papers, 1681-1930, The London Archives

11. Foster, Joseph (arranged by): Register of Marriage in Gray's Inn Chapel, 1695-1774

12. Fletcher, Reginald D. (ed.) (1910): The Pension Book of Gray's Inn (records of the honourable society) 1569-1800, London; p.ix

13. Thornbury, Walter (1878): Old and New London, Volume 1, London; p22-31

14. Jones (1981); p73

15. Ibid; p46

16. Currency Converter: 1270-2017, The National Archives; accessed 13 Nov 2024

17. Jones (1981); p257

18. Ibid; p49

19. Ibid; p43

20. Liverymen of the City of London, from a speech delivered by J. Rowlands to partliament in 1891; accessed 14 Nov 2024

21. Jones (1981); p52

22. Will of Robert Bullivant, Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury Series PROB 1, The National Archives

23. London Apprenticeship Abstracts, 1442-1850, abstracted and indexed by Cliff Webb, for findmypast.com

24. Freedom Admission Papers, 1681-1930, The London Archives

25. Jones (1981); p51

26. The Poll of the Liverymen of the City of London at the Election of Members of Parliament (1710), London

27. Whigs and Tories, UK Parliament webiste; accessed 15 Nov 2024

28. Ogborn, Miles (2021): Sir John Cass, The Royal African Copmany and the Slave Trade, 1705-1718, University of London

29. London: Centre of the Slave Trade, Historic England; accessed 16 Nov 2024

30. 1872 Ballot Act, UK Parliament; accessed 16 Nov 2024

31. Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies Volume 7: 1662-1674, Her Majestry's Stationary Office, 1889; accessed via British History Online, 16 Nov 2024

32. Jones (1981); p45

33. Kester, Robert A. (1972): The Sacheverell Affair: its causes and implications, University of Richmond

34. Heckethorn, Charles William (1896): Lincoln's Inn Fields and the Localities Adjacent, London; p74

35. A List of the Poll [...] for the City of London, 1713, London

36. List of the Persons Who have Polled [...] for the City of London, 1722, London

37. Freedom Admission Papers, 1681-1930, The London Archives

38. St Dunstan-in-the-West, burial book 1709-1739, The London Archives

39. City Livery Companies, City of London Public Relations Office (2011)

To go back to the Dobbs-Davis tree, click here